One of the prime entries in this year’s edition of the New York Film Festival (which runs from September 30th to October 16th) is a movie that played there in 1973, “The Mother and the Whore” (October 5th-6th). Directed by Jean Eustache, it has been very hard to see in recent years; the film was released here on VHS, but not until late 2021 did the rights holder, Eustache’s son Boris, agree to its restoration, theatrical rerelease, and eventual DVD issue. The movie won the Grand Jury Prize at Cannes in 1973 and was widely hailed as an instant classic, but it’s an elusive one, in ways that have nothing to do with availability. It’s the great post-1968 movie (with reference not to the calendar year but to the epochal events in France and the young people marked by them). It’s a radical movie, yet its radicalism is ironic, even evasive, because, far from embodying the ideals of the May Days, “The Mother and the Whore” is radically conservative.

“The Mother and the Whore” is an overwhelming film. It’s overwhelming in its length (just over three and a half hours) and in its emotional intensity—it’s a self-consuming masterwork that seems to burn itself up as it passes through the projector. It’s a film of rage and self-punishment, of arrogance and humiliation and, ultimately, of ferocious irony about pleasure and power, desire and submission. (I won’t worry much about spoilers; the movie is so vast that, regardless of any description, it leaves whole worlds to be discovered in the viewing.) Yet, for a film that blazes with the spirit of youth, its sense of cinematic form is surprisingly traditional. What’s original in its style is the sheer profusion of dialogue, which exceeds in quantity, density, and tone even the talk in contemporaneous films by Éric Rohmer (eighteen years Eustache’s elder). Where Rohmer’s cinematic language is dialectical, Eustache’s is torrential. The characters in “The Mother and the Whore” don’t so much talk with each other or even at each other as bare their souls verbally and pour out confessions in soliloquies—especially the movie’s protagonist, Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Léaud). Those confessions are largely avowals of traditional, even reactionary, values, decrying the new morality of the sixties and the democratic values of technocratic modernity. “The Mother and the Whore” advances ironically, by moving backward, not just in its aesthetic but in its substance.

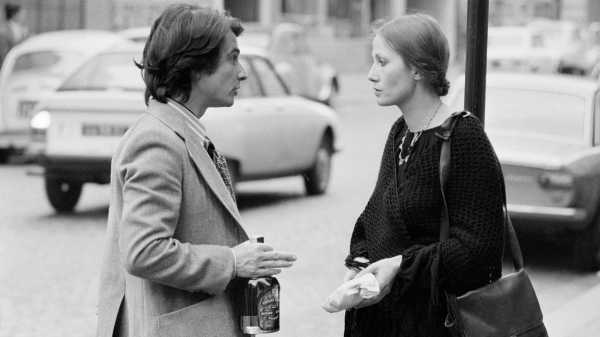

In “The Mother and the Whore,” there’s no mother and no whore. There’s a woman named Marie (Bernadette Lafont), who nurtures and indulges Alexandre; there’s another, named Veronika (Françoise Lebrun), who has lots of casual sex and says so. The title is cynical, macho snark that’s aimed at them; they aren’t the movie’s protagonists but the two women the protagonist finds himself caught between in a sharp-edged triangle. Like the entire film, the snarky title embodies Alexandre’s perspective. He seems to be about twenty-five and is a member of the non-working class—he’s a dandyish intellectual, a writer who rarely writes but who heads daily to the famous Left Bank café Les Deux Magots in order to read, and spends the rest of his time philosophizing with friends and picking up women. Alexandre lives with Marie, in her apartment; she’s closer to thirty, runs a small, hip clothing store, and supports Alexandre financially in his flibbertigibbet adventures. Veronika, a twenty-five-year-old nurse, lives in a cramped and sordid room at the Paris hospital where she works; Alexandre sees her at a café and literally chases her down the street to get her name and phone number. As he pursues a relationship with Veronika, Marie overcomes her jealous resentment and admits her to the household.

There is a third woman, no less essential to the movie. She’s only onscreen for two long scenes, but I consider her to be the movie’s center; she’s not in the title but, rather, is hidden in plain sight. In the film’s first extended sequence, which runs more than ten minutes, Alexandre wakes up early and borrows a neighbor’s car in order to stalk a university student named Gilberte (Isabelle Weingarten), a former partner who has left him and whom he finds and confronts—on the sidewalk, on a park bench, in a café (where she pays for his meal)—in an attempt to overwhelm her with a frenetic rush of logic-chopping rhetoric and philosophical ardor in the hope of persuading her to marry him that very day. This whirlwind sequence unfolds Alexandre’s romantic desperation, torrentially intellectual word-spew, and essential traditionalism. They meet again, by chance, a few days later; she tells him she’s going to marry someone else, and Alexandre executes another series of dialectical capers to talk her out of it, complete with a bitter accusation that she’s marrying for money and status, a sociological lament that she had the advantage of being raised in an era when she was taught good French and good morals, and a perverse suggestion that Gilberte should have a daughter who, at eighteen or nineteen, may well fall in love with him.

Under the guise of the freewheeling threesome promised by the title—and which, spoiler alert, ultimately comes to pass—Eustache delivers a work of presciently radical reaction, as Alexandre lashes out at French society at large, charging that its longstanding corporate conservatism and its late-sixties egalitarian progressivism alike are imposing uniformity and degrading traditional aesthetic and moral values. He pairs his anarchism with authoritarianism, with a nostalgia for brazen power. In the company of an unnamed friend (Jacques Renard) who treats him to a stock of Nazi memorabilia, Alexandre (who knocks on his door with the five-knock code for “Algérie Française,” a slogan supporting France’s colonial occupation of Algeria) looks back longingly at the time when French women swooned over men in military uniforms; now, he says, they fall for “executives,” “professionals.” With “The Mother and the Whore,” Eustache delivers, in the person of Alexandre, a modern story of the post-1968 age of the carefree libertine as a story of power, of desire existing solely to be satisfied by any means necessary. It’s a drama of constraint—the constraint of the other to conform with one’s own desires—and, as such, it’s a drama of cruelty, of implicit sadism, complete with its ugliest political manifestations.

In effect, Alexandre is a primordial incel, albeit one who has lots of sex. The movie gives fullest vent to his regressive ideas in its overwhelming centerpiece, a scene that lays bare the decisive wound of his rejection by Gilberte—a scene that’s focussed on her but from which she is absent. The entire movie rides on the negative energy of this rejection; everything that follows, from his relationship with Veronika to his introduction of her to Marie, is Alexandre’s effort to compensate, his fallback option. The black hole of that disaster occupies a colossal scene that forms the core of the film, an encounter between Alexandre and Veronika in the Café de Flore (then the headquarters of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir) that is, seemingly, a brazen affront to feminism and to women. Alexandre tells Veronika about his relationship with Gilberte, saying that it was violent, admitting that he hit her so hard that he “broke something.” Second, Alexandre, who’d already casually suggested that abortionists are murderers, further denounces Gilberte for leaving him for a man who’d helped her get an abortion. “Abortionists are the new Robin Hoods, the new knights of the Middle Ages,” Alexandre says, with scathing sarcasm. “They no longer protect the weak and defenseless, they set women free from the vile thing in their bellies. Scalpels replace swords, probes replace sabers, and women always fall for their liberators.” Eustache, using one of the movie’s few but telling strokes of cinematic form to emphasize the importance of this scene to Alexandre, to Veronika, and to himself, films it with the characters face to face, looking and talking directly into the camera.

With an apt attention to these elements, “The Mother and the Whore” comes off as a kind of horror film, a revelation of monstrosities that Eustache observed, imagined, perhaps even felt. In any case, it is largely autobiographical. Despite the movie’s great length, Eustache wrote and filmed it very rapidly, because he was in the middle of a situation very similar to Alexandre’s. As Luc Béraud, one of Eustache’s assistants on the film, details in his memoir “Au travail avec Eustache” (“Working with Eustache”), the director was then living with a shopkeeper named Catherine Garnier, was also in a relationship with a nurse named Marinka Matuszewski, and had formerly been in a relationship with a woman who’d left him—namely, Françoise Lebrun, who in the film plays Veronika.

The movie’s eruption of emotional and social monstrosities is inseparable from its warm, tender, compassionate view of the daily lives of workaday young people, such as Marie, whose sense of style is linked to the dull routine of her days in the store, or Veronika, a devoted nurse who drowns her numbness in rapid sexual encounters. Both women are amused, enticed, and fascinated by Alexandre’s intellectual expatiations about, say, suddenly imagining a highway as “the vestige of an ancient civilization,” his riffs on the films of Murnau, or his descriptions of the colorful clientele of a predawn café. Eating at the luxurious, highly decorated restaurant Le Train Bleu with Veronika (via money he borrowed from Marie), he expresses his lifelong class and cultural resentments along with his epicurean tastes. “Not having money is no reason to eat badly,” he says. “As a child, I would steal books. I claimed poverty is no reason not to cultivate yourself.” That monologue continues with a sly cinematic pivot: “There are people rich enough to do nothing, who do things. They even make good things: movies, for instance.”

“The Mother and the Whore” at times comes off as a kind of Freudian assassination of the French New Wave, with which Eustache personally associated. Born in 1938, he came to Paris at twenty, watched movies, and frequented the offices of Cahiers du Cinéma, where his wife at the time, Jeanne Delos, was a secretary; Béraud recalls that “although he only wrote two articles, he was part of the ‘clique.’ ” The movie’s cast embodies the prime modern traditions of the French cinema, against which his film was in radical revolt. Léaud won fame as a teen actor in François Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows,” the movie that, in 1959, put the New Wave on the map of world cinema, and had entered another cinematic dimension in Jean-Luc Godard’s “Masculine Feminine,” from 1966—in which his character impregnates his girlfriend (Chantal Goya), who considers self-administering an illegal and dangerous abortion. (Léaud also starred in Eustache’s 1966 featurette “Santa Claus Has Blue Eyes,” which Godard partially financed.) Lafont got her start in a short film by Truffaut, starred in his 1971 feature “A Gorgeous Girl like Me” and in several early features by Claude Chabrol, and acted in Jacques Rivette’s nearly thirteen-hour-long “Out 1.” As for Weingarten, she’d only been in one film—as the star of “Four Nights of a Dreamer,” by Robert Bresson, one of the New Wave’s elder artistic heroes.

Filming in stark, spare black-and-white, in cramped apartments and tiny cars and bleary cafés and humdrum streets, Eustache caustically strips the sheen of high artistry and street poetry and fine feelings from the Parisian intellectual realm that the New Wave romanticized. Godard, who’d started as something of a right-wing anarchist in a vein similar to Eustache’s, became a leftist of increasing (albeit self-sacrificing) orthodoxy; Truffaut, who was also on the left, was a conspicuous part of the Parisian beau monde; Rohmer, a rightist, filled his movies with the dignified and respectable culturati; Rivette adapted Diderot, Racine, and Balzac. Eustache fills “The Mother and the Whore” with popular songs from prewar France; delights in the banal exaltation of a radio preacher; mocks Jean-Paul Sartre and his bourgeois Maoism; and waxes nostalgic about earlier and crueller times, complete with praise of duelling and the brazen assertion that “we must encourage injustice.”

In removing the genteel veneer that had become associated with the New Wave, what Eustache laid bare was also personal experience, albeit at second hand. There’s a crucial subtext or, rather, sub-movie undergirding “The Mother and the Whore”: Eustache’s own 1971 film “Numéro Zéro,” a feature-length interview with his grandmother Odette Robert, who speaks at length about the rigors and horrors of her life in a village near Bordeaux in the early twentieth century—from poverty and disease, to crime and humiliation, to the oppressions of German Occupation and the emotional ravaging of daily life that went with all of them. For Eustache, the underlying furor of his grandmother’s life also represented a richness of experience that nothing in progressive modern France could replicate. Her apparently awful life is the loam of collective memory, the historical soil from which modern France, with its comforts and refinements, its presumptions of economic and social progress, has sprung, while paving over it and concealing it with the very works of art that embody such progress culturally. “The Mother and the Whore” comes off as a living reproach to the cinephilic referentiality of New Wave filmmakers—the suggestion that they turned toward movies in order to turn away from appalling realities.

Scratch any of us—us men—Eustache is saying, and you’ll find a monster lurking; scratch us hard enough and we’ll fight; and, in the eternal combat between men and women, the only way to beat us is to break us. The ending of “The Mother and the Whore,” with its blend of feminine vulnerability and feminine power, is the road map for that ultimate conquest. It features a heroic and self-flaying monologue by Veronika, delivered shatteringly by Lebrun in a pair of long takes (one running more than five minutes). The speech, in its furiously hot-blooded substance, vaporizes the post-1968 myth of libertine frivolity and embodies something like a one-woman counter-revolution in real time. It is only the setup, however, for a mighty, emotionally violent ending: the soundtrack fills with Veronika’s majestically derisive laughter as she accepts Alexandre’s marriage proposal and browbeats him into the corner, where he cowers like a chastened boy who finally gets his comeuppance. His moment of triumph is his moment of ultimate submission; she will make a man out of him.

“The Mother and the Whore” comes off as a fractured counterpart to Marcel Ophuls’s 1969 documentary “The Sorrow and the Pity,” which blasted away the myth of wartime France as a land of resisters amid a few isolated collaborators, and also revealed the ongoing presence of the unrepentant far right in latter-day France. Eustache, in shattering the façade of progress, the view of French youth as a free-spirited brigade of progressive intellectuals, and the illusion of the post-May world as a sexually carefree romp of flower children, revealed the ongoing endurance of the country’s oppressive and violent past—but, far from decrying its persistence, portrayed its unslaked ugly furies as the true source of the country’s best new art, starting with his own. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com