People might mean well, but, benign or not, when somebody asks, how’s your mama doing, my impulse is noneya. As in none of your business, which often construes to “she’s fine” or “doing well” or “good,” depending on who asked. But, to keep it 100, I ain’t sure. Let Mom tell it, she’s a single woman. Let me tell it, she’s a married woman who’s been devoted to the most abusive polygamist of all time. Mom, adamant, has filed for dozens of separations and umpteen divorces, but over and over she’s found herself reconciled into a union that has lasted beyond its silver anniversary.

CIRCA 1985

Mom’s ceremony has been a movie stuck on repeat for more than half my life. Since it’s oh so tough, after umpteen years, to tell what’s fact and what’s fiction, my memory of this story is more or less how it happened. Trust, at its nexus it’s all true. All of it. The nuptials occurred the year I was nine, ten—no older than that. The particular night, I blew into Mom’s room in our house on Sixth Avenue, found her at the foot of her bed with her head pressed in her hands and asked her what was wrong. She said nothing. She said she’d be fine. I told her I was hungry and she said she’d fix me something to eat in a few. This answer would have given most any other knucklehead all the excuse they needed to raid the cabinets or the fridge, but for me, a kid who’d been spoiled and couldn’t cook, it meant waiting till she shook off enough of what was troubling her to rise.

That didn’t happen till late that night, so late it might’ve been early morning. Mom came into my room, at God knows what hour, and promised me a trip to Burger Barn. Burger Barn burgers, the tastiest burgers in northeast Portland, the whole state of Oregon, maybe on earth, were my favorite thing to eat—period—which is why it took not a word more to coax me out of our crib. We climbed into our yellow Datsun B210 and made a left here and a right there (maybe we listened to the radio, maybe we didn’t), and before I knew it we turned off Interstate Ave. into the parking lot of a decrepit-looking motel. The motel’s name, I can’t call it, but its sign was cracked or buzzing or burned out. Such were all the motel signs on Interstate back then.

Mom climbed out of the Datsun and, still fiending for my burger, I hopped out and followed her up flights of steps to a room. She knocked and stood back. She seemed composed, but also discomfited. She knocked again and the man who answered, in hindsight, had to be the paragon for his kind, but that night, with zero priors, all I could think was dude’s lips looked dusted. “Hey, li’l man,” he said, and did something to distract me or Mom or us both from a long, bald gaze.

The room smelled like what they were doing, but again, with no priors, I had little clue. A friend of Mom’s, whom I’ll call Dawn, was in the bathroom, and, when she sashayed out, her hair, which most days was relaxed salon-straight and combed backward, was a spiky mess and she was dressed in somebody else’s oversized shabby gear. The vision of dude and Dawn were all I needed to see the urgency in persuading Mom to leave, to break out, to motor fourth gear to Burger Barn, where my empty stomach would get its fill, and she and I would be safe.

She said soon. She said for me to take a seat and proceeded to elope in a bathroom, where her friend and a dude with frosted lips witnessed her hasty foolish nuptials. I watched a snatch of Benny Hill or “Kung Fu Theatre” or whatever former prime-time hit was on the tube that time of night, watched it with my eye twitching like the kids in my class who couldn’t sit still and what I didn’t recognize as a premonition wrenching my empty gut. The ceremony must’ve been brief, a commercial break at most, and although I was sheltered from the altar I have come to believe the following as facts: there was no ring proffered, no kiss between lovers, and no vows vocalized, but in that foggy bathroom the woman who matters most to me, a woman who up to then I’d never seen drunk or high off nothing, inhaled her “I do.”

I DOs

The oldest recorded evidence of marriage between a single man and single woman is from ancient Mesopotamia. Those unions, which by law featured a marriage contract, had the primary intent of insuring social order. For most of recorded history, starry-eyed romantic love had little to do with whom one married. The ancient Greeks thought lovesickness was a kind of insanity. The Protestant theologians preached that husbands and wives who loved each other too much were sinful idolaters. In the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church’s Great Council met and, to combat secret marriages and people marrying in forbidden degrees of consanguinity, ordered that they be announced so that people could make knowing objections to their legitimacy.

The result: whosoever objects to the union of these two people, speak now or forever hold your peace.

Yes, oh, yes, I wish I could’ve objected to Mom’s union with science, wish I could’ve warned Mom what the substance that was her groom would do to the part of her brain called the ventral tegmental area (VTA), explained that when we do something pleasurable, our brain cells release dopamine, a little chemical messenger, which, once released, travels across a gap between nerve cells called a synapse, binds to a receptor on a neighboring cell called a neuron, and sends a signal to that cell, which produces aaaaaaaaaaaaaah—so much pleasure. Under normal circumstances (meaning, minus the substance), once the dopamine sends the signal, it’s reabsorbed into the sender cell by what’s called a dopamine transporter. Maybe Mom would’ve left it at the altar if she’d known that her groom would thwart that cycle, that it would attach itself to the transporter and prevent the normal reabsorption process by the receiver cell. That disruption would cause the dopamine to build up in the synapse and super-hella overstimulate the receptors, which, in seconds, would feel to her like aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaah—the bliss of all bliss. The ecstasy would last no longer than a few of her favorite radio songs and then—POW!—her dopamine levels would drop and she’d feel a low like she’d never felt, a crash that would send her chasing that most inimitable high once, twice, for far too long.

If I could return to the night of her nuptials, I would caution her about that fugitive joy, the plunge, and the ultimate damage the substance that was her groom would do to her orbital frontal cortex, the part of her brain that decides the salience of a stimulus—harm that she couldn’t undo. Bet she’d’ve turned runaway bride if she’d known how restless it would make her feel, how paranoid. Or that her groom might give her a stroke or stop her heart. How a weekend getaway with it could waste her from her normal slim to gaunt.

And if the science wouldn’t convince her maybe she would’ve heeded me presaging all the nights she’d forsake us, my younger brothers and me—three boys she once claimed to love more than herself—the times, after a long absence, she’d sorrow through the door and sleep for days more alone in the dark. Maybe my mother would’ve refused to give her hand if I prophesized the night she’d break barefoot out of a dope house with a police dog barking at her heels, or the night a stone-fisted neo-barbarian would beat her to gashes and aches everlasting. It’s possible I would’ve persuaded her with a forecast of the stints she’d spend in rehab—in- and outpatient—the months she’d spend serving a prison sentence, the arrests and convictions that, an age later, would prevent her from jobs that would pay what she needs to survive. There’s a chance I could’ve lobbied her to say “I don’t” with the news that her eldest—Mitchell Jackson, the baby boy she named for her favorite great-uncle—would end up in prison a decade or so later for selling triple-digit grams of the same substance to which she was about to commit.

CIRCA 1990

It would be foul of me to mention what happened with Mom and not say a word about what happened with me. It happened when I was fourteen, maybe fifteen—when I was an old boy who felt older, who’d resolved I’d exceeded my threshold of mother-where-art-thous. The details: one day after school, I approached a homeboy who I knew sold dope and asked him if he would give me some to sell. He asked me if I was serious, and when I confirmed he fronted me a few shards, quoted me what I owed him, and sent me on my dubious way. Since I was patient not none, that night or a night in the near future, I crept out of the house with the cream-colored shards stashed on my person and a porous dream of double-up tucked in my chest. It was a Langston Hughesesque dream if there ever was one, because not only did I not double up that first night, I did not single up that first night either, a failure that felt as though it might never end. But for a time I kept faith, stood out in the shadows among others determined to clock dollar. It was frightening and exhilarating all at once. It was ineffable seeing that world demystified, witnessing firsthand the landscape, which by that time my mother had been roaming for years. There was also a part of me that half hoped I’d see her and that the encounter would coerce her into acknowledging the secret that was secret to fewer of the folks we knew than she or I could’ve imagined. There was also the fragile hope that if Mom had to confront where her “I do” had delivered us, she’d sue ASAP for differences irreconcilable, and that would be that. Gavel strike. There was also some comfort in the theory that every night I survived the ruck of rock-toting aspirants was a night my mother too could shamble home from a like scene alive. As I said, though, those first few nights, it was clear my peon sack would not be multiplied. So I hyped myself to return it to my homeboy (lucky for me he really was a homeboy) and explained that I’d made a mistake. It would be a while before the shards became bricks, and seven years before cops pulled up behind my ’86 Honda, and arrested me for the first and the last time.

To limit the number of marital mistakes, all major religions have embraced some version of a matchmaker. In Christianity, a cleric or another trusted person is often tapped to connect potential partners. In Buddhism, matchmaking parents—sponsors—of a prospective couple are encouraged to consult an astrologist and, if unsuccessful, are urged to query an inner-world deva. In Judaism, a shadchan—whether official or not—has connected partners over the ages. In Islam, a young person makes a dua to Allah to find the right person and the family, most often the parents, catalyze the matchmaking by inquiring among their network for prospects. If the couple and the family agree, the couple meets, chaperoned, until such time as they determine their compatibility. If they believe themselves a good fit, the families further investigate the character of the potential mate. Then the couple prays Salat-l-Istikhara—a prayer for guidance—and agrees to pursue marriage or dissolve their dealings. Dawn and her chalk-lipped co-conspirator were the ostensible matchmakers of Mom and the substance that, posthaste, became her spouse, but I’ve come to believe that someone who is of equal if not more culpableness for her union is a man she’s never met.

Ricky Donnell Ross, a.k.a. Rick Ross, was born in Tyler, Texas, in 1960, to Annie Mae Ross (maiden name Mauldin), the daughter of an East Texas sharecropper. Rick’s father, Sonny Ross—a former Army cook and later pig farmer and cleaner of oil tankers—bounced on the family when Rick was a boy, and in 1963 Annie migrated with Rick and his older brother to California, where they lived with his mother’s brother. One night, that uncle attacked his wife and Rick’s mother, and, as Rick watched, his mom pulled a pistol from her purse and killed her brother. She spent time in jail but was released and reunited with her boys. Annie Mae and her dead brother’s wife bought a house in South Central near the 110 Freeway—a home that would shape untold destinies. Rick attended South Central’s Manchester Elementary and Bret Harte Junior High (neither of which taught him how to read), and during that time evinced a penchant for hustling: pumping gas for tips, peddling lemonade, mowing lawns. Though quick, agile, and coördinated, Rick conceded by junior high that he wouldn’t grow big enough to star in football or basketball. But then one day Rick and one of his homeboys moseyed down to a local park where a man was holding tennis clinics. It didn’t take many clinics for Rick to realize he’d found his sport, so much so that by ninth grade he was recruited by Dorsey High, a magnet school in Baldwin Hills, known then and now as the Black Beverly Hills, to play for the team. Rick earned all-league tennis honors his first year at Dorsey High and all-city honors every other but quit before he earned his diploma. Rick prevailed upon a man he’d met through tennis to help him enroll in a job training program at the Venice Skills Center, where he wound up studying auto repair—while he stole cars and worked at a chop shop on the side.

Circa late 1979, early 1980, Rick and his homeboy Big Ollie were sitting on his porch. One of his homeboys who was back from college called up. “Man, I got the new thing,” he said. “Come thru.” Rick jumped in Ollie’s ’64 Impala, pumped a dollar’s worth of gas in the tank, and rode out to where his homeboy was staying. Once inside, that homeboy pulled out a baggie with little tubes of white powder. “I’m tellin’ you, this is the new thing. This here cost fifty bucks.” He handed it to Rick to inspect. “Stop lying,” Rick said, eyes widening. “This little thing worth fifty bucks?” He gushed how it was so small the police would never catch him with it. “Here, go ahead and take this and see what’s what with it,” his homeboy said. Rick accepted and he and Big Ollie motored back to the house he lived in with his mom and aunt. They rushed inside and inspected their product, hadn’t a clue if they’d gotten their hands on some authentic cocaine and, if they had, what they’d do with it. So they hopped back in the Chevy, braved their gas peril, and hunted the hood for wisdom.

This was around the time that in South Central on some blocks you’d see a dozen or more dudes out selling PCP sticks. But cocaine might as well have been some shit from another planet. They had just about given up on apt consultants when Rick ran into an old pimp he knew from the neighborhood. The pimp was hip, offered to rock the powder if they let him test it. Post what first appeared a mystical cooking process, the O.G. produced a small white nugget. He cut a shard off the nugget, smoked it, and smacked his lips. “This taste all right, but I’ma need another piece to make sure it’s good,” he said. “You don’t wanna be out there sellin’ somethin’ that ain’t right.” The old pimp chipped another piece, smoked it, smacked again. “Yeah, this here is proper,” he said. “I’m gone go ahead and smoke the rest of it, and I’ll get you back on Friday.” And, just like that, Rick and Ollie had been beat. Rick’s career dealing cocaine, in a few deep inhales, seemed finished. How was he supposed to call up his homeboy to cop more dope when he didn’t have the fifty bucks? His boy Big Ollie wanted to kill the O.G. “Man, we can’t do that,” Ross said, and sat around his house brooding.

Hours later, the O.G. pimp who’d beat him out of the fifty dollars of dope pulled up to the house with someone who wanted to spend a hundred bucks. Rick phoned the homeboy who’d given him the first product. “I ain’t got that fifty I owe you, but I got somebody over here that wanna spend a C-note,” he said, and his homeboy zipped over to serve the O.G. pimp. The O.G. pimp came and went, left and returned, to Ross’s mama’s house with more people who wanted to cop. Quick, so quick, Rick began clocking a couple-few hundred a day and, all the while, hounding people to teach him how to chef the product he’d soon call “ready rock.”

On one of those early days, Rick drove out to visit his old mentor at the Skills Center, someone he hadn’t seen since his dope bounty began. “How you doin’?” his old mentor asked. “What you been doin’?” Rick, after some reluctance, revealed he’d been selling dope, expecting at least a lecture. “Oh, yeah? Come with me,” his mentor said, and drove him out to his house. “How you think I got this house, this new car, these clothes, all these jewels, all of this on a teacher’s salary?” he asked, and told Rick that he used to sell dope, and that he was still connected. That revelation kicked off Rick and his ace Big Ollie buying dope through the mentor, reinvesting their profits, procuring larger and larger quantities till the point they became much more than the mentor was willing to sell. The mentor, as amends, introduced them to his connect, a man who, unbeknown to Rick, was a Nicaraguan exile. The prices the Nicaraguan quoted turned Rick’s smile wide as an L.A. boulevard. I’m finna get rich, he thought. However, months into their transacting, the Nicaraguan got shot in the spine and hospitalized. The convalescence of Rick’s Central American connect led to a man named Oscar Danilo Blandon, another Nicaraguan exile, who adopted Rick and his homie as customers. It ain’t fat-mouthing in the least to claim that Blandon forever changed the course of Rick’s life. Blandon was a direct associate of one of the biggest drug traffickers in the world: a Nicaraguan named Norwin Meneses. Blandon, by way of Meneses, whose cocaine was as plentiful as California sunshine, helped Rick corner what was then a fledgling crack market in South Central L.A. Ricky Donnell Ross from Tyler, Texas, bootstrapped his way to “Freeway” Rick Ro$$, a “ready rock” marketing genius, a South Central drug tycoon who’d claim “[God] put him down [on earth] to be a cocaine man.”

Rick’s self-sanctified ascension seemed to happen in a flash, but the truth is it was millennia in the making. Pre-Incan tribes of the Andes chewed the leaves of the coca plant. That cultural practice existed in the region for eight thousand years and was exclusive to its inhabitants until the sixteenth-century Spanish conquest of the Incans, whereupon it was introduced into what the Eurocentrists call the Old World. In the nineteenth century, 1859, a talented Ph.D. student isolated the primary alkaloid of the coca plant, and in the custom of other alkaloid nomenclature—morphine, codeine, nicotine, strychnine, quinine—christened the substance cocaine. It showed up in operating rooms as an anesthetic, was used as a key ingredient in innumerable nostrums and beverages—one of which evolved into Coca-Cola—and became a go-to stimulant for recreational users.

The plentitude of cocaine for mass consumption came into question at the top of the twentieth century, a time when America’s newspaper of record ran headlines like “Cocaine Evil Among Negroes” and “Negro Cocaine Evil” and the infamous “Negro Cocaine ‘Fiends’ Are a New Southern Menace.” Congress set in motion the eventual criminalization of cocaine (and opium) with the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, a law that imposed a special tax on “all persons who produce, import, manufacture, compound, deal in, dispense, sell, distribute, or give away opium or coca leaves, their salts, derivatives, or preparations, and for other purposes.” The legislation, intended to ban all non-medical use of cocaine, succeeded in making the narcotic scarce for Negroes and almost all else save the mobsters who cornered distributing it on the black market and the Hollywooders who were agreeable to paying a high premium to keep partaking.

Notwithstanding the enduring indulgence of the rich and famous, cocaine usage declined through the nineteen-sixties. Mom’s eventual matchmaker was born at the top of that decade, and, by the time Rick was in junior high, cocaine use was experiencing a renaissance in places including the Bahamas, Miami, and L.A., due in large part to the media dismissing it as harmless and glamorizing it on the regular in music and film, as well as a new way of consuming the drug dubbed freebasing. That resurgence set the stage for the nineteen-eighties proliferation of crack users and, of course, Rick willing himself into a mythic matchmaking magnate. In the Rose City, Rick or his direct emissary, or else somebody who dealt his product second-, third-, or fourth-hand, or else somebody who’d heard of him and wanted to emulate him, or who knew not of him but nurtured kin ambitions, facilitated untold unions (one was too many), my mother’s intimate espousal among them.

CIRCA 1995

What’s the first without the last? Well, this isn’t the final, as in end, of it all, but it’s what signalled for me that I wouldn’t have the heart-strength to keep on.

Context: this particular night had to be half a decade or so after my first barren nights of curb serving, so I was well into my more fecund period of dealing, but was still at least a year prior to my arrest and the Friday the thirteenth in 1997 that his honor Henry Kantor sentenced me to prison for sixteen months.

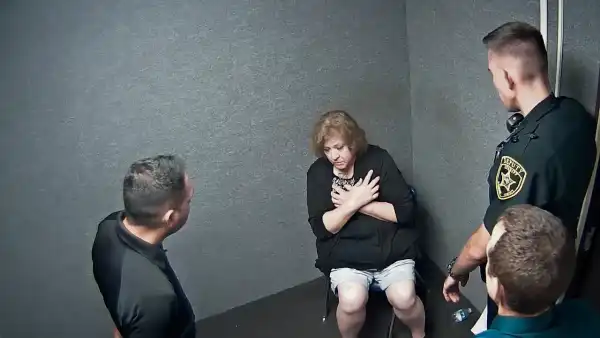

There was this dude I used to serve: a man who a couple months later would get caught with cocaine I sold him and, instead of snitching, serve an eight-year prison bid. One night, dude paged me to his crib without hint of what for save that it was urgent. Since I trusted him, I rushed over. Soon as I got there he, who most nights was vociferous as shit, nodded me toward the back room without a word, his face all sorts of sombre. When I got in that back room, I discovered my mother, smelling like she smelled, with her eyes gleaming white in the dark. “Mitchell, give me somethin’ and I’ll go home,” she said. “Just give me somethin’, please.”

Maybe I shook her. Maybe I didn’t. “Hell no!” I said. “Fuck no!” I said, and felt struck that instant with a brand-new dread. At the time, I’d known dudes who’d served their blood, knew one who’d even sold to his mama, but, never mind the next man’s deeds, that thought never, and I mean never in life, entered my realm of possibilities. If selling dope to my mama was what it had come to, I knew for absolute certain it would have to come to an end for me.

THE YEAR 2007

Ain’t much dubiety on the details here. This was a time I flew home from New York to surprise my family. When I got to Mom’s crib, I knocked and waited, expectant for the smile she’d beam the moment she saw me. No one answered, so I knocked and knocked. When it was clear no one was home, I searched under the front mat for the key and let myself in. On a normal day, house empty or not, the TV would’ve been running with the sound muted and screen flickering. But on that day the screen was dead gray.

When I’d come home a few months prior, Mom’s living room was plush with a full set of rent-to-own digs: leather couches, coffee and end tables, a sparkle-bordered dining-room mirror. But, this time, all that fancy new decor was gone, and left in its place was a salvaged leather love seat and not much else. With a bad feeling tumbling around my insides, I set down my bags and rambled into Mom’s room—a dim cove fragrant with Mom’s cancer stick of choice. The room looked ransacked, and I rooted the chaos for clues. When I didn’t find any, I wandered into my brother’s room, where I saw wind sucking the curtain through a hole the size of a head in the window. For a better look at the state of things, I hit lights. Up down. Up down—nothing. Hmmm, I wondered, and tried the switches in the kitchen and bathroom, neither of which worked. The light company shutoff was proof enough that Mom was off once again renewing her vows. I slunk back into the living room, wilted onto the couch, and let my eyes leak.

I don’t do that often.

The rare times I do, it’s never for pity.

We—the we being Mom and her three boys—don’t want nor need no one’s pity.

No. One.

None.

Mom, the substance that has been her spouse, my brothers, and me maketh a non-nuclear family whether we acknowledge our ties or not. But things could be far, far worse. We’ve survived, although not unscathed, Mom’s union. Mom has survived, although not unharmed, decades of anniversaries with an abusive spouse. And, before anybody gets to criticizing me and mines, know this: my mama ain’t no failure. Mom’s achieved the triumph of raising three grown boys—all of whom have escaped murder, drug habits, long-term prison terms (ask around, anything less than a nickel is almost unmentionable), illiteracy, gang membership, and much else on the long list of perils that rank us right up there with northern spotted owls.

There’s an old recovery maxim, “once an addict, always an addict,” the logic being that an addict must choose moment by moment not to abuse. Well, Mom has spent decades of her adult life living moment to moment. Some of those moments have been more successful than others. This is a truth I have come to accept. It’s a truth I’ve had to accept and am stronger for it.

For millennia marriage was considered a civic duty and part of the institution of social responsibility. Recall the Greeks who believed love a psychiatric ailment. The French in medieval times believed love a “derangement of the mind” curable by sex. In fact, the idea of marrying for love didn’t take hold in Western culture until the industrial revolution. Mama Edie and Bubba raised Mom to believe in marrying for love: The I-take-you-to-be-my-husband love. To-have-and-to-hold-from-this-day-forward love. For-better-or-for-worse love. Through-health-and-sickness love. Through-good-and-bad-times love. Till-death-do-us-part love. It is a love for all the days of one’s life. The love that binds all blessed unions. History suggests that the pledge Mom exchanged in a shabby motel in the small hours of the morning—the same night that she promised me a Burger Barn burger that I ain’t seen to this day—will last on some level till death cleaves her from this earth. Some would call that a fated existence, but what if all these years my mother has been honoring her vow?

THE YEAR 2012

Vow.

That was supposed to be the last word. For drafts and drafts and drafts that was the last word, but now my conscious won’t let that be it. Because the night in the motel, the one on Interstate, it seems I either made it up or conflated it with another occasion. On everything I love, for all those years, that’s what I thought happened. And can you fault me for not having the courage to ask my mother to set me straight? We all know how it goes, right, or we should know or we’ll learn: whether we seek or seek not the toughest truths, they’ll find us.

As proof, I offer the time Mom and me spent an evening visiting spots in Northeast that were memorable to us and telling each other stories about why each place mattered. That night, she directed me to a house on Alberta Street that used to be an after-hours spot. “There,” Mom said. “That’s where I took my first hit.”

CIRCA 1985

Credit due for me at least being spot-on about the year. My great-granddad Bubba—with whom Mom had been charged with caretaking—left on a trip to the supermarket up the street and hours later was presumed lost in a bout of Alzheimer delirium. Mom ventured out with her friend Dawn that night, during what she remembers as family-wide angst. In the wee hours, Dawn dragged Mom to the house that was the after-hours spot in Northeast, and real quick Mom’s friend gave her the shake. Sometime that night, Mom wandered upstairs and into a foggy room where Dawn and a small crew of others were sharing what turned out to be the most ecstatic ephemeral high this side of paradise. On the second floor of that house on Eighteenth and Alberta, in the presence of her best friend and a gathering of future fated spouses, my mother said her doomed “I do” to it-never-was-nor-could-be-right.

Mom stumbled into The House on Sixth the next day. By grace, Bubba had been found, but, also by then, the family was worried about her. The list of those concerned included her father, who’d made his way to the house. My grandfather pulled Mom aside.

“Where were you?” he said.

“Oh, I was out,” Mom said. “Out smokin’ crack.”

“Crack,” he said. “And what’s that?”

“Well, it’s this cocaine,” Mom said. “It’s like a little rock. And you put it on a pipe and you smoke it.”

“I see,” he said. “Well, do you think that will be a problem for you?”

“No, I don’t think so,” Mom said. “I don’t think it will,” she said. “I’m sure it won’t be a problem.”

This piece is adapted from “Survival Math: Notes on an All-American Family,” out this month from Scribner.

Sourse: newyorker.com