Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

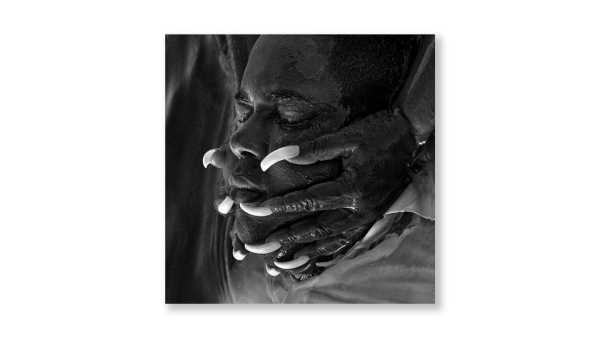

When it comes to the many types and shades of Biblical metaphor being stretched into the secular world, the metaphor of baptism does the best, and heaviest, lifting. There’s a plain understanding to the rite: If cleanliness is what you’re after, it works. If a renewed lease on living is what you’re after, it works. If, even, a sort of resurrection is what you’re after, it also works. On the cover of “Angels & Queens—Part I,” the first half of a two-part album by the gospel-infused band Gabriels, the singer Jacob Lusk appears chest-deep in a river, a woman’s hand on his head, preparing to push him under in an act of baptism. Even if one did not know the long path that Lusk took to arrive here, the cover sends a clear message: this is someone who is reborn, not who he once was, better than before.

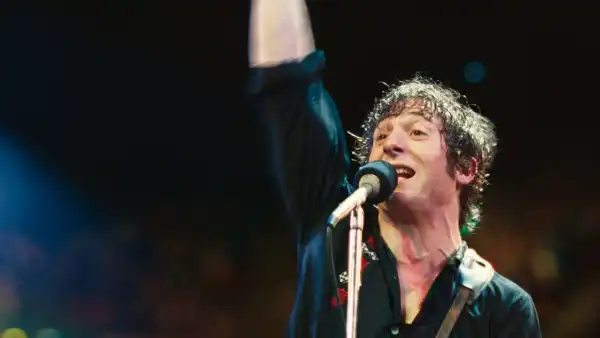

There’s a video of Lusk from 2011, performing on the tenth season of “American Idol.” He’s wearing a white button-up shirt, baggy light-blue jeans, and diamond earrings. When his name flashes on the screen, the text below says that he’s a spa concierge, twenty-three years old, from Compton, California. He sings a brief, stunning rendition of the Billie Holiday song “God Bless the Child,” in which he wrings out the sound in each vowel, shakes all the loose change out of each syllable, runs the word “mama” together, repeatedly, until it becomes a single extended word. He wears the effort of his singing on his face, eyes closed, cheekbones defined through a half smile, a half-strained expression on the high notes. But his body sways evenly, a hand mapping the vocal peaks and valleys. One of the judges, Randy Jackson, leans back and throws his arms in the air. That performance was a high-water mark for Lusk, who had a rough experience on “American Idol,” both onstage and off. He was the only Black male performer among the final thirteen contestants that season, and he endured racialized abuse on blogs, and racialized criticism from judges who, according to Lusk, told him that he was over-singing, and, when he pulled back, told him that he wasn’t singing enough. Nonetheless, Lusk came in fifth place, got to share a stage with Kirk Franklin and Gladys Knight, and appeared on the “Today” show.

But the experience of “Idol” haunted Lusk, who has said that he left the show thinking that he was incapable of singing. His confidence was shaken; opportunities fell through. Lusk became a choir director, working in the background for artists such as Diana Ross and leading and arranging choirs for live performances and commercials. On one such commercial call, he met the producer Ryan Hope and the composer Ari Balouzian, who asked Lusk, now in his mid-thirties, to come and record with them in Palm Desert. Later, Hope and Balouzian were further impressed after encountering Lusk where he was most comfortable: inside his church. Thus, Gabriels was born. In 2016, the three musicians met a couple of times a month to record in the midst of their day jobs. It was low-stakes work, with Lusk arranging and singing songs that he loved and regaining his voice along the way. The fruits of this labor were a pair of EPs: “Love and Hate in a Different Time,” released in December, 2020, and “Bloodline,” a year later. The former was praised by Elton John, who called it “one of the most seminal records I’ve heard in the last ten years.”

The praise and momentum from 2021 flowed into “Angels & Queens—Part I,” which was released in September of last year to critical acclaim. Gabriels is a collection of many hands. Balouzian and Hope aside, there were more than twenty additional collaborators on “Angels & Queens—Part I.” The production is lush and full, a wall of sound built from colossal snare drums and frantic strings, waves of horns and textured piano. And, even with all of the beauty of these moving pieces, Lusk’s voice is the engine that makes the machine go. He most comfortably sings in a swelling falsetto, sometimes swooping down to a lower register that feels steeped in mourning, and occasionally dipping into a near-whisper to twist the emotional knife. He has the rare gift of an enormously powerful voice that neither overpowers the material nor shrinks from it. This level of craft is perhaps born out of Lusk’s multifaceted background: singing in the church as a young person, serving as a backup singer for Nate Dogg, experiencing the crucible of “American Idol,” and crafting choir arrangements for other artists. His greatest gift is the ability to give a song exactly what it needs and nothing more.

The second half of “Angels & Queens” was released earlier this month, not as a separate album but as six new songs conjoined with the original seven into a thirteen-track LP. The new songs, like the opening track, “Offering,” build upon the sonic template set forth in the first set, but many of the new tracks ascend toward a polyphonic crescendo that arrives earlier in the song, and doesn’t just arrive once but arrives many times over. In “Offering,” the tune begins with Lusk singing over the trickling notes of an upright bass. Then strings begin to poke their heads through the quiet notes. And then keys, a choir, and horns enter all at once, exploding into a chorus. A great artist teaches the audience how to consume their work, and Gabriels has set an agreement of anticipation. How a song begins is not how it will end, and that is a trick of the church, too—at least of a good church, where the songs take whatever detours they take because someone singing got into a good groove or a good mood or a bit of both, or because the piano player noticed someone dancing in the aisle and looped back around to the same notes, and then a few other someones decided to join in. Gabriels embraces this practice not only by setting an expectation of a song’s shifting—rising to a massive swell or descending to some beautifully harrowing depths—but also by using the song structures to honor a varied pace, so that, in some cases, a song presents as sort of a mini-suite. For example, “Professional,” another of the new tracks, spends its first act with Lusk’s voice swaddled in strings, singing in a register so low that it resembles moans more than actual language. By the second act, his voice is fully enlivened, accompanied by sparse piano. And then, in the song’s final moments, a steady percussion enters over the piano and Lusk’s voice—singing, “You were supposed to love me . . . you were supposed to protect me”—becomes layered, and then backed by actual mournful moans. As Lusk repeatedly sings “I forgive you,” the song turns over into the next track, “We Will Remember,” in a manner so seamless that, if a listener is not actively watching the progress bar on her streaming service, she won’t be aware of the transition. “We Will Remember” takes a similar shape to “Professional,” but it borrows from some of the previous song’s earlier movements. The strings return, and, halfway through, a choir fully emerges, singing in small, short bursts over Lusk’s repetition of “You were supposed to love me.” With an economy of language, the two songs operate as four, or five, different songs in one.

This is another gospel gesture that presents itself in the work of Gabriels. Lusk is a singer of incredible repetition. He sings in a loop, returning to the same lines as though he, and you, are both uncovering the words for the first time. When the song “Great Wind” gets moving, Lusk is heard over an enthusiastic choir and a frantic arrangement of percussion and keys, singing the phrases “great wind” and “joy is coming” with renewed enthusiasm during each rotation, as if he’s just looked down and found something irresistible in his path.

Perhaps there is no great distinction to be made between “Angels & Queens” in its individual parts. It feels, to me, as if it was meant to be listened to in this new form, both iterations linked together into one Gabriels album. The tracks from “Part I,” like the hopeful piano ballad “If You Only Knew” and the reverb-drenched “The Blind,” fit seamlessly into the grander project, the grander vision of Gabriels, in which every song feels like a unique house in a single neighborhood, with the listener being guided through a series of rooms awash in fascinations, relics of love, of loss.

The complete “Angels & Queens” ends with the same song that concluded the first release. Titled “Mama,” it takes on an even richer tone here, as it finishes with the sound of horns and Lusk, reassuring, “Mama, don’t you cry / it’s gonna be all right.” The latter phrase is repeated on a loop, with Lusk’s falsetto never surrendering its beauty but sounding slightly less convinced with each repetition as the song fades. There’s a beauty in this, too. A message wedged beneath. There is the song that is sung to convince a beloved friend or elder that the world will survive itself, and that we might survive along with it. And then, beneath that, is the song burdened with the weight of what we know. Somewhere in between is where faith lives. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com