The big color self-portraits in Lyle Ashton Harris’s exhibition “Flash of the Spirit,” at Salon 94, are so playful that their pleasures—visual but also sensual, like the feeling of a soft breeze or rough bark on your skin—register before their intelligence settles in. Since the late nineteen-eighties, Harris, a native New Yorker who grew up partly in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, has been using himself (in performances as well as pictures) as a lapidary tool to dismantle preconceptions about race, gender, and sexual identity, and to construct an ongoing, oneiric memoir about African diasporic life.

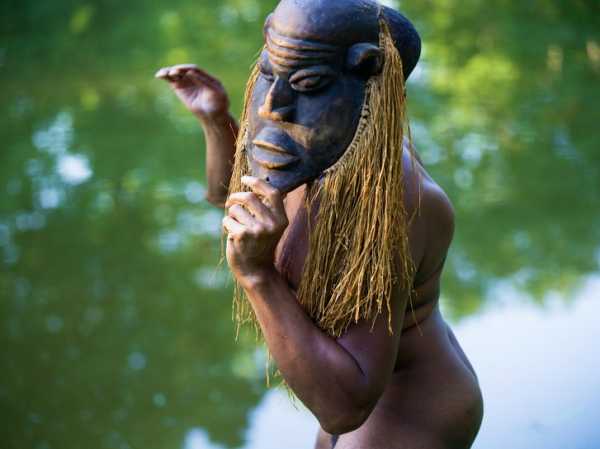

“The Thinker,” 2018.

For his new pictures, the artist posed, nude or nearly so, in African masks, many of them from his uncle’s collection, rooting an en-plein-air masquerade in his private history. The backdrops of the images are personal too, bucolic locales that have meaning for Harris: the Hudson Valley and the gay beach meccas of Provincetown and Fire Island.

“Nocturnal Guardian #1,” 2018.

“Zamble at Land's End #2,” 2018.

The canon of photography is full of masks, from Edward Curtis’s documentation of native North Americans in ceremonial garb, at the turn of the twentieth century, to Cindy Sherman’s use of latex masks to heighten the grotesqueries of her “Sex Pictures,” in the mid-nineties. Perhaps the most famous example is from 1926, when Vogue published a photograph by Man Ray of his lover Kiki holding an exquisitely stylized wood carving of a woman’s face from Côte d’Ivoire, the same place where the elaborate black-white-and-red Zamble antelope mask that Harris wears in three of his pictures was carved. But the dualities in Man Ray’s image—between primal and modern, sculptural and human, African and European—collapse in Harris’s hallucinatory images, redressing centuries of colonialist decontextualization.

“Flash of the Spirit,” 2018.

The striking “Afropunk Odalisque” is the show’s lone interior and one of two homages to the model Laure, best known as the “other” model in Édouard Manet’s painting of the recumbent “Olympia,” from 1863: she posed as the white woman’s maid. In Harris’s gender-bending reclamation, the figure reclines on vibrant green-and-gold Ankara wax-print cloth, wearing a red-and-black loincloth and a mask crowned with cowrie shells. Some of the works are titled in African languages, including “Tafakari,” meaning “meditate” in Swahili; the diptych ups the ante on Surrealist doubling, as Harris crouches above a lake that reflects his masked image back to him and then repeats it, flipped, as a mirror image. A photo of the artist standing tall on green grass against a black sky, beneath a waning white moon, is titled “Ashé,” a Yoruba word that summons the hope of Harris’s art—it means “the power to bring about change.”

“Afropunk Odalisque,” 2018.

Sourse: newyorker.com