Photograph from Alamy

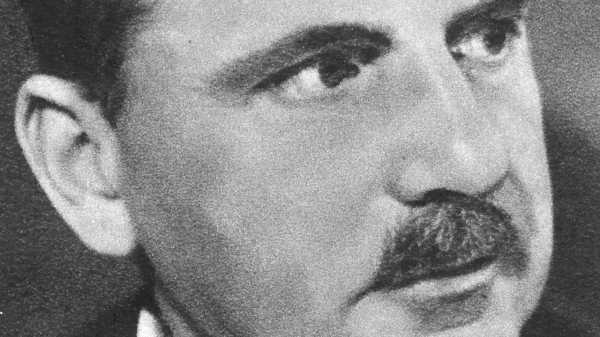

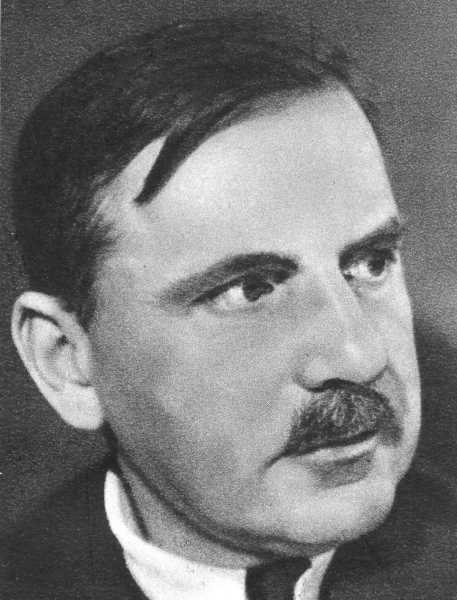

The Swiss composer Othmar Schoeck, who lived from 1886 to 1957, is little known outside his native land, but his moments of fame have been as striking as they are strange. For one thing, Schoeck gained the admiration of several leading writers of the twentieth century. Hermann Hesse ranked Schoeck’s songs alongside those of Schubert and Schumann; James Joyce considered him a rival to Stravinsky; Thomas Mann also thought highly of him. A further quiver of notoriety followed in the nineteen-seventies, when, as Calvin Trillin related in this magazine, students at Amherst College launched an absurdist organization called the Othmar Schoeck Memorial Society for the Preservation of Unusual and Disgusting Music. The group is best remembered for having precipitated the meeting of the illusionists Penn and Teller. At the time of their fateful encounter, Penn was riding a unicycle and Teller was selling pencils emblazoned with Schoeck’s name.

The work that prompted the formation of the Society was Schoeck’s orchestral song cycle “Lebendig Begraben,” or “Buried Alive,” composed in 1926. An Amherst student named Weir Chrisemer, the Society’s founder, came across a recording of it and found it to have “no redeeming merit.” The same piece so thrilled Joyce that he knocked unannounced on Schoeck’s door, in Zurich, and said, in German, “Does the man live here who composed ‘Lebendig Begraben’?” Most listeners, on first encountering Schoeck, will probably fall somewhere between the extremes of Chrisemer and Joyce. This is music of recessed, elusive beauty, although it has its moments of wildness and weirdness. Only an exceptional performance can reveal its depths. The great German baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau argued convincingly for Schoeck a few decades ago. Christian Gerhaher, perhaps Fischer-Dieskau’s most formidable modern successor, has made an even stronger case in recordings of “Notturno” and “Elegie,” two Schoeck cycles for voice and ensemble. The Sony Classical label released Gerhaher’s account of “Elegie” earlier this year, and I have been listening to it obsessively, a little more mystified and mesmerized each time.

Who was Othmar Schoeck? However often or seldom the question is asked, it is answered superbly in “Othmar Schoeck: Life and Works,” a 2009 biography by the Swiss-based musicologist Chris Walton. Walton begins by noting that Schoeck’s personality resists stereotypes of Swissness. Far from being tidy, thrifty, or cuckoo-clock-like in his habits, the composer was “notoriously unpunctual and disorderly, with holes in his socks, his manuscripts strewn on the floor and trodden underfoot.” He went to bed late, rose late, borrowed money without paying it back, and conducted numerous affairs with women who found him oddly irresistible, at least at first. He sometimes wrote in haste; his creative energies were intermittently engaged. Music history tends to look unkindly on such messy, inconsistent figures, preferring those who put the brand of genius on works large and small. But when Schoeck applied himself fully, as in “Notturno” and “Elegie,” he rivalled the best of his time.

The Schoeck œuvre is capacious: five large-scale operas, a fair quantity of concertos and chamber music, assorted choral pieces, and, most impressively, hundreds of songs. Schoeck had an instinctive command of the art of the German lied, which had experienced its golden age in the hands of Schubert and Schumann and had undergone a late flowering in the fin-de-siècle songs of Hugo Wolf, Gustav Mahler, and Richard Strauss. Although Schoeck was a composer of broad stylistic reach, opening himself to the harmonic jolts and rhythmic jabs of the early twentieth century, he seemed most himself when he was ambling through the German Romantic twilight, his seductive melodic inventions tinged vaguely by irony, by aerial quotation marks. His music is suffused with a sense of having arrived too late in the day.

Schoeck’s late-Romantic fluency helped to bring about the great shame of his career: the première of his final opera, “Das Schloss Dürande,” in Berlin, in 1943. No reactionary, Schoeck had lamented Hitler’s rise. But when Nazi cultural functionaries began praising him as a custodian of heroic Germanic tradition, he succumbed to the offer of a high-profile première, at the Berlin Staatsoper. Schoeck’s act of complicity shadowed the remainder of his career, and a heart attack in 1944 effectively ended his major creative phase. “Das Schloss Dürande,” a fable of the French Revolution based on a novella by Joseph von Eichendorff, is rich in inspiration, but its text, by the Nazi-aligned poet Hermann Burte, is atrocious. (Even Goering thought it stupid.) Four years ago, the Swiss conductor Mario Venzago presented a new version of the opera, with a revised and de-Nazified text by the writer Francesco Micieli. You can hear the fascinating, disorienting results on a recording on the Claves label: it’s an opera floating in historical limbo.

No apologies are necessary for “Elegie,” which had its première in 1923, against the backdrop of Schoeck’s tempestuous affair with the pianist Mary de Senger. There are twenty-four songs in the cycle, drawing on poems by Eichendorff and Nikolaus Lenau. Schubert’s “Winterreise,” not coincidentally, has the same number of songs: like the Schubert, “Elegie” will be a journey to the end of psychological and spiritual night. The opening setting, of Eichendorff’s “Wehmut” (“Melancholy”), sets the tone: “True, there are times I can sing / as if I were cheerful and happy / but tears come unbidden in secret / and then my heart is set free.”

At the outset, we are deposited in a bewitching nowhere: a chord of B minor, with a B-flat hanging above it, followed by a ghost procession of harmonies that fail to resolve the clash of the opening. Most of these chords are major or minor triads with extra notes attached, giving the feeling of a smudged or blurred tonality. Arnold Schoenberg, in his book “Harmonielehre,” designated such music “hovering tonality”—tonality without solid roots. Both of the opening phrases end on a chord of B-flat minor, suggesting that B-flat will be the eventual destination. Indeed, it is, but the point of arrival is unstable and provisional: a wavering between major and minor modes, an interplay of light and shadow.

The vocal line is dominated by quarter notes, in an even, chant-like motion. Gerhaher, born to sing such music, applies burnished tone, precise diction, and a hint of a cabaret artist’s arched eyebrows. The ensemble weaves dark magic around him. Perhaps surprisingly for a composer so identified with the voice, Schoeck was an orchestrator of genius, and the timbres he elicits from a fifteen-member ensemble—four woodwinds, French horn, string septet, piano, timpani, and gong—arrest the ear at every turn. Heinz Holliger, who conducts the Basel Chamber Orchestra on the Sony recording, chooses to augment the string section, which only enriches the effect. The opening chord of “Wehmut” is voiced by winds and muted strings. An English horn then doubles the singer as the other winds unfold that lugubrious kaleidoscope of disconnected chords. When the strings steal back in, the violas are playing sul ponticello and tremolando—the bow trembling spectrally at the bridge.

The sonic wonders proliferate from there. The flute unfurls lunar ditties; the horn calls out forlornly, like the last survivor of a vanished hunt. In “Nachklang” (“Echo”), a repetitive cawing line for the clarinet had me thinking of Philip Glass. The piano has oddly loungey touches—for example, a hazy, off-center chord at the end of the second song. The percussion is used with extreme economy: the timpani play for seven bars in total, and the gong has a smattering of quiet strokes. Perversely, the gong stays silent in “Vesper,” even though the text all but demands it: “The evening bells are already ringing through the silent valley.” Instead, chiming sounds are consigned to the piano while other instruments dominate the texture with a relentlessly slithering serpentine figure. What does it represent? The text speaks of bells, of a rustling linden tree, of the lover’s wish to be lying in the grave. I thought, reluctantly, of burrowing worms.

In its cyclical patterns and fixed ostinatos, “Elegie” borders on emotional claustrophobia. Walton writes: “It is at times as if the very building blocks of melody and harmony were themselves receding into distant memory, with the singer/narrator holding on obsessively to the only fragments over which he has any control.” It’s all the more startling, then, when a lush, expansive, lullaby-like tune surfaces in the final song, “Der Einsame” (“The Lonely One”). Just before, the lower strings introduce a near-quotation from Puccini’s “Tosca”—the mellow lament that accompanies the writing of Cavaradossi’s farewell letter. All this makes for a satisfying finale, though in some ways it is the most conventional aspect of a profoundly unconventional work. The heart of “Elegie” is that music of fraught stillness and serene unease.

Are any members of the Othmar Schoeck Memorial Society for the Preservation of Unusual and Disgusting Music prepared to reconsider the butt of their scorn? At least one is. When I sent Penn Jillette a query and a link to Schoeck’s “Notturno,” he wrote back, “This is so sad and beautiful.” He went on to savor the oddity of the moment: “When I was seventeen years old in Greenfield, Massachusetts, I juggled toilet plungers and threw them around Wier Chrisemer and made them stick (much harder than knife throwing) while an Amherst college orchestra played a very odd and funny instrumentation by Wier of the ‘Saber Dance.’ ” Now, he reported, he was in Melbourne, drinking a decaffeinated vegan flat white and listening to the formerly unlistenable Schoeck. In sum: “You know it has been a long strange trip.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com