Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

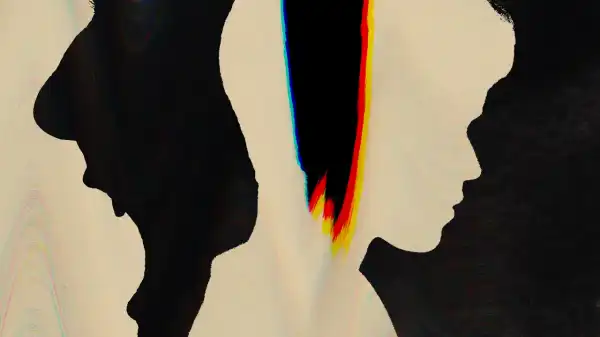

Netflix currently ranks the British miniseries Teenager as the most-watched TV show among American audiences. The streaming platform surrounds its methods for achieving these results with a host of absurd claims. Yet this drama about a 13-year-old boy suspected of murdering a classmate seems to be slowly finding common ground with critics and viewers. Will Teenager give Americans culture shock? There’s a true crime story unfolding in this tale of a white teenager and his alleged heinous crime. How did the girl’s death happen? Is the boy really her killer? Quit. Once you’ve finished the first episode, the detective element of Teenager will be resolved. The question it poses, and refuses to address, is why.

Yet Boyhood exhibits a continuous visual movement. The creators, Stephen Graham and Jack Thorne, never forget their theatrical duty to perform, along with their moral ambitions; one reinforces the other. Each of the miniseries’ four episodes, each about an hour long, is shot in a single take. I’m not going to go into how impressive this technique is, as critics are wont to do when a team makes such an ambitious decision. The vaunted single take is often an illusion, created by clever editing, with no alchemy being introduced into the script. But Boyhood doesn’t succumb to the temptation of trickery; the show couldn’t have been made any other way. The camera is treated as a judgmental instrument.

Many might find the first episode of the show unbearable. An English town – in West Yorkshire – at dawn. We begin in a patrol car, where two officers, Luke Mascombe (Ashley Walters) and Misha Frank (Faye Marsay), are fastening their seatbelts. Mascombe receives a call from his son, who is trying to run away from school; filled with obvious pride, Mascombe informs Frank that his son is talking to him rather than his mother, as he is more gentle. “Adolescence” explores the distance between father and son, how biological and domestic closeness can make it difficult to understand each other.

Bursting into a modest middle-class home, officers in riot gear claim they have grounds to search the home of a family of four. The father, Eddie Miller (played by series co-creator Graham, a veteran English actor), is furious and confused. He is broad-chested and very present, and so we suspect the officers are after him. But their target turns out to be a boy named Jamie, played by Owen Cooper, who was 14 at the time of filming. This is Cooper’s screen debut. The young actor conveys the confusion surrounding the potential of his changing body. Cooper doesn’t mimic an adult’s idea of puberty; he embodies it. In fact, in this moment of chaos and fear, he looks like a teenager. Mascombe tells him he is being arrested. Jamie urinates. The officers allow Eddie, outraged and exhausted by the search, to come over to help his son. They then explain that they are bringing Jamie in for questioning: he is suspected of murdering his classmate Katie.

Mascomb takes Jamie to the station. Jamie’s mother, Manda Miller (played by Christine Tremarco, a wonderful woman trying to hold together a broken family), stays with his sister Lisa, and Eddie drives to the station in his car. The drive is filmed in real time, and we, like the characters, fill our heads with theories and recriminations along the way. We feel what Eddie feels: this is a case of mistaken identity. This boy is incapable of killing anyone.

The script has a nuanced interest in aspects of English ambiguity. The politeness, the “love” at the end of grueling and desperate interrogations. “Look at your father. Come up here,” the nurse tells Jamie at the station, as she takes the boy’s blood for DNA testing. The scene – it continues with Jamie being stripped and photographed, the camera turning away from him so that we see only the flash of a police camera – makes a claim to realism. This is not a story from the headlines, but from the tortured heart of a culture.

Mascomb, who is black, leads the interrogation. We see no action or violence in the interrogation room. Mascomb focuses, suddenly filled with authority, while Eddie, sitting next to Jamie, retreats into a pose of crossed arms in disbelief. Eddie didn’t know his son was out with friends the night before; Eddie didn’t know his son was following Katie; Eddie didn’t know his son had gotten rid of his sneakers and that he had a knife. Jamie and Mascomb are locked in a conversation that Eddie can’t join in on. Another person may know his child better than he does, and what could be worse for a depressed, overworked father?

Sourse: newyorker.com