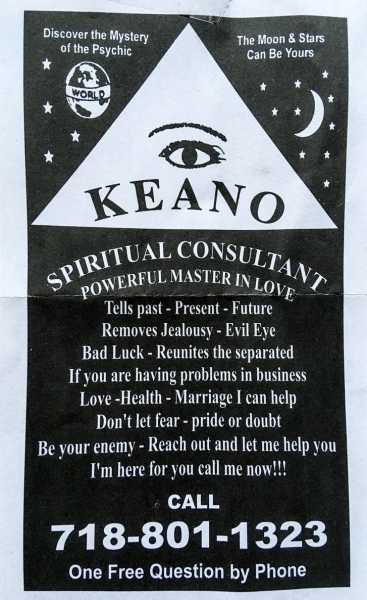

Most New Yorkers who use public transit with any frequency have, at one point or another, come across a Keano flyer. Printed on cheap paper and littered throughout the interiors of subway cars, the handouts advertise the services of a “Spiritual Consultant, Powerful Master in Love.” Under an image of a third eye, Keano offers aid for a slew of psychic dilemmas—“Removes Jealousy,” “Reunites the separated”—if only the skeptical subway rider would call the number printed at the bottom of the page.

When the Belgian photographer Thomas Freteur came across these ads, after moving to New York, in 2017, he became curious about the psychic, or psychics, behind them. The next year, he called the number, hoping to photograph Keano, if such a person existed. But no one picked up, and he had equally little luck visiting the shops that advertise palm readings in neighborhoods like Hell’s Kitchen. Eventually, through online networks like Yelp and through word of mouth, he tracked down several psychics who agreed to be photographed and began travelling from borough to borough to visit them in their homes and where they practice. The group appears in his photo series “New York Psychics.” “My point is not to make you believe,” Freteur told me recently. The aim of the project, which is part of a larger photographic study of spirituality, was to find men and women who believe in their own gifts, and who just might persuade others to believe, too.

Marina.

In the case of Paul Beaudet, an older man living in Hamilton Heights, the beginning of his practice as a psychic was accompanied by another sort of awakening. Beaudet—or Paul the Palmist, as his Web site calls him—came out as gay late in life, around the time that he began his career as a self-described spiritual minister. In Freteur’s portrait, he sits in an armchair with his eyes closed, chin tilted at a slight angle, palms facing upward. On the wall behind him, brushed strokes of color in an abstract painting appear to emanate from him like an aura. In the caption for an accompanying photograph of Beaudet’s bedroom—a yellow wall, adorned with Catholic iconography and images of shirtless men—Beaudet says that he used to be invited to Christmas celebrations at the school where he once taught geography. “But, when they realized I became a psychic, they rejected me!”

Barbara.

In another portrait, two women, Marge Othrow and Emily Grote, are captured standing side by side in a little yellow house in Clinton Hill, looking out a porch window. The women became friends when Grote rented an apartment from Othrow, a practicing medium. At the time, Grote was working in the corporate world but beginning to access her gifts as a medium, and in Orthrow she found the support system she needed. In the portrait, Orthrow is partially obscured by the reflection on the window, imparting a ghostly, spirit-like quality to the older woman; Grote is more of-this-world, stoic next to her friend and mentor. In the caption for the portrait, Grote describes the conflicting voices that complicated her decision to pursue what she calls her “present life.” Her fourteen-year-old daughter once asked her, point-blank, if she was a fraud.

Marion.

Stefanie.

In another portrait, Nikenya Hall, who became an energy healer and intuitive consultant after moving to New York, sits in the tiny Flatiron co-working space that she rents for her practice. Hall is the only lively thing in the claustrophobic room, which has been outfitted in the usual office décor—an inoffensive geometric print, a tropical-looking plant. In the caption, she explains that she gives readings in the rented space, rather than in a more casual environment, such as her home, in order to project credibility and build trust with her clients. Hall, whose portrait exudes a quiet confidence, remains wary of the stereotypes that are attached to being a black female psychic. “I didn’t want to be a $5 fortune-teller. As a black woman, I didn’t want to be misunderstood,” she said, adding, “I have that gift; it’s not a plan.” For a long time, she didn’t talk to her friends about her new career.

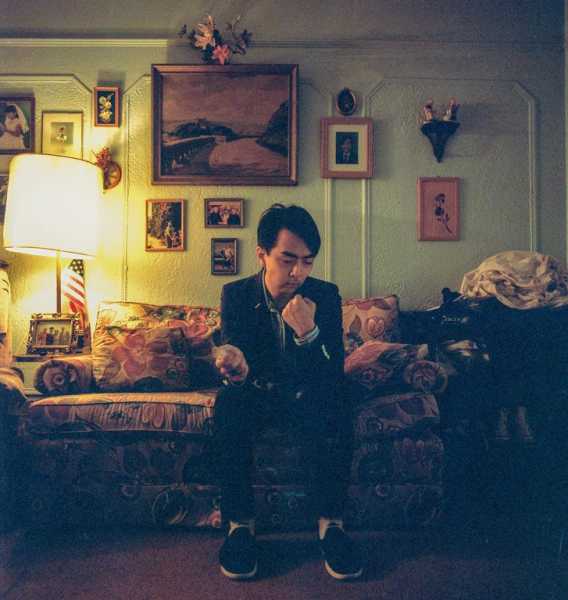

Michael.

Nikenya.

Apart from the mystic art hanging on their walls, the common talismans and tools of the trade, these psychics are as varied and distinctive as you’d expect any group of New Yorkers to be—they are “people that could be like anyone, could be like you and me,” as Freteur put it. Yet, with their furrowed brows and reserved body language, many seem to be carrying a certain burden. Perhaps they feel the responsibility of heightened awareness, an extra-sensitivity. Or is it the weight of others’ skepticism? Freteur’s portraits bring us only as close as photographs can to reading their subjects’ thoughts.

Levadia.

Marge and Emily.

Terence.

Janet.

Sourse: newyorker.com