Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Charles Frederick Worth, the 19th-century fashion designer widely considered the founder of haute couture, was not a modest man. “Madame, who advised you to come to me?” he wondered, addressing a potential client in his Paris atelier, prepared to pay the high fees typically demanded for his services. “If you want me to dress you, you need an introduction,” he explained. “I am an artist of Delacroix’s caliber.”

Worth had many reasons for such confidence. His most distinguished client during a fifty-year career was an empress, but queens, socialites, actresses, and courtesans also sought his craft. His “upholstery-style” dresses, adorned with drapery, ruffles, embroidery, and fringe, vividly illustrated the sociologist Thorstein Veblen’s concept of “conspicuous consumption.” At a time when married women’s property rights were strictly limited, a Worth dress signified that its wearer was connected—through family, marriage, or the passion she could arouse—to at least one large fortune. This was important in a rapidly changing society, where wealth, concentrated in the hands of a few, could be gained or lost in an instant.

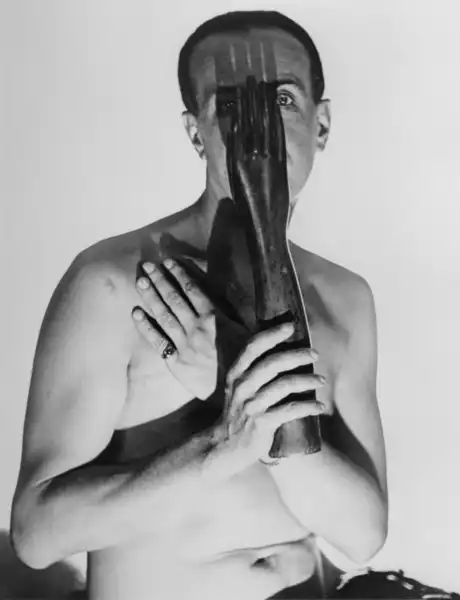

Today, viewers of our rapacious age can cross Paris’s magnificently gilded Pont Alexandre III (itself a product of the Belle Époque) and enter the vast halls of the Petit Palais, built around 1900, where “Worth: Inventing Haute Couture” is on display until September 7. Organized in partnership with the Palais Galliera, the exhibition features more than 400 rarely seen works. Clothes, paintings, photographs, and objets d’art trace the history of the Worth house from its founding by Charles Frederick in the age of crinolines to its Edwardian revival under his sons Jean-Philippe and Gaston, and on into the 1920s and 1930s, when his grandson Jean-Charles carried Worth’s opulent style into the Jazz Age, launching perfumes, befriending artists, and posing nude for a series of photographs by Man Ray. The exhibition argues that in doing so, the house set the standard for many of the conventions and myths that still define the creation of haute couture.

Photograph by Jean-Charles Worth, 1925. Photograph by Man Ray / Man Ray Trust / ADAGP, Paris / Image Telimage, Paris

“Luxury, theatricality, and historicism” are the key characteristics of Worth’s style, explained fashion historian Sophie Grossior, co-curator of the exhibition with Marine Kisel and Raphaëlle Martin-Pigalle, one morning at the Petit Palais. She stood next to a day jacket with a nipped waist, high collar, and puffed sleeves, made of deep blue velvet and decorated with arabesques in pale violet satin. (On the wide, Renaissance-style collar, the pattern is inverted: the arabesques are blue, the background is violet.)

This gorgeous jacket might have appealed to Renée, the tragically spendthrift heroine of Emile Zola’s novel “Murder.” One Parisian winter, caught up in a wild affair with her stepson, R

Sourse: newyorker.com