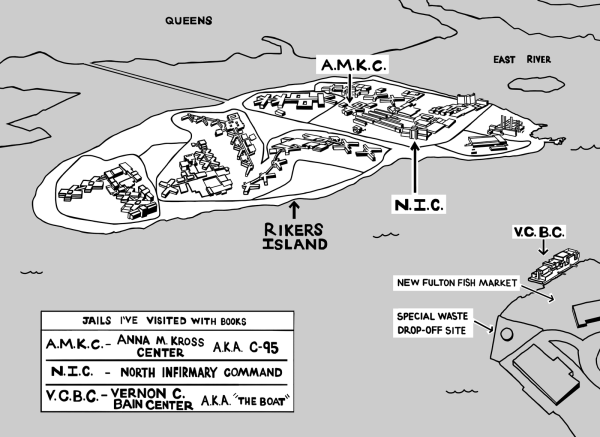

For more than a year, I’ve been working in New York City jails as a library assistant for the Brooklyn Public Library. I started out at the jail complex on Rikers Island. Now I work at the Vernon C. Bain Center.

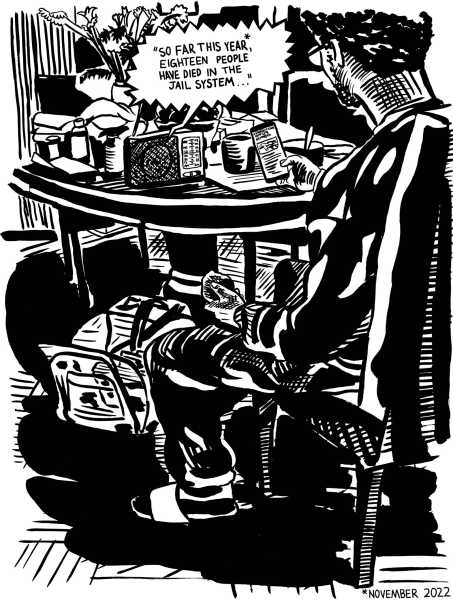

When I turn on the radio before work, I often wonder whether I’m going to hear more bad news about the jail system.

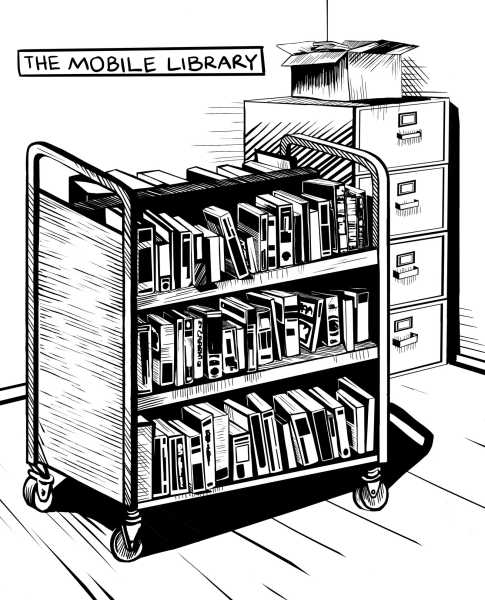

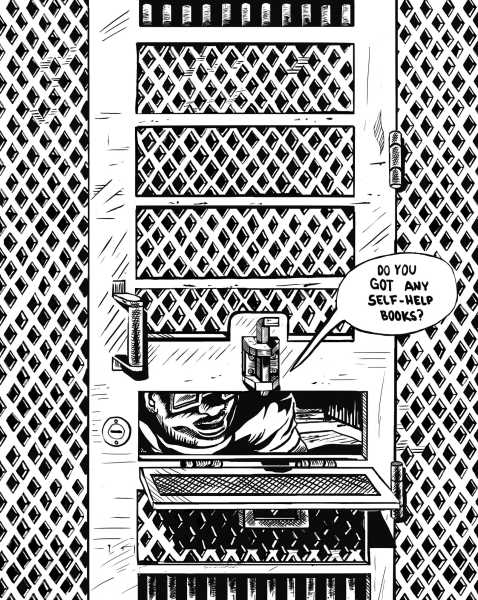

The Department of Correction (D.O.C.) doesn’t give us any bookshelves, so at Rikers my colleagues and I rolled a squeaky cart from dorm to dorm.

Phones and cameras aren’t allowed on Rikers, but I’m an illustrator. Sometimes I saw things that I felt compelled to draw from memory later.

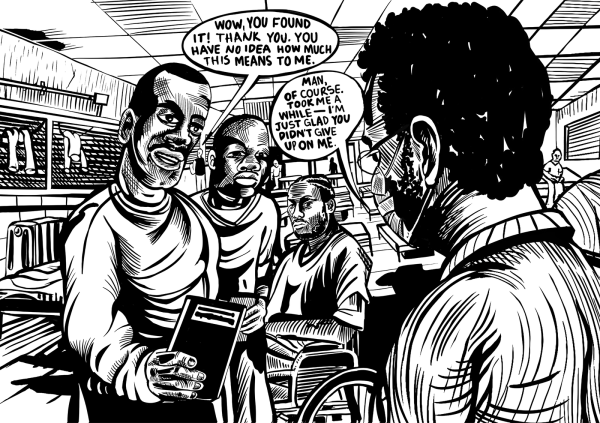

I’m always moved by the sense of gratitude and warmth that some people express when we’re able to get them the books that they asked for.

Rikers is one of the world’s most notorious jails. Incarcerated workers built it on a foundation of garbage, and New York City packs it with about six thousand people, most of whom are awaiting trial. Many simply can’t afford bail. Some stay for years.

The Vernon C. Bain Center, which everyone calls the Boat, is a jail barge across the water from Rikers. It smells like fish and trash.

There are parts of the jail system that we no longer visit, because we don’t feel safe there. Other parts have lost library access because we don’t have enough staff.

In a dorm in the Rikers infirmary, I often heard men talking on pay phones with their wives and kids. Others swapped snacks or flipped through legal documents that they needed at trial.

On the second and third floors of the infirmary, the hallways were so narrow that the book cart barely squeezed through. Men here were caged by themselves in “protective custody” and could rarely leave their cells. I passed them books through a slot.

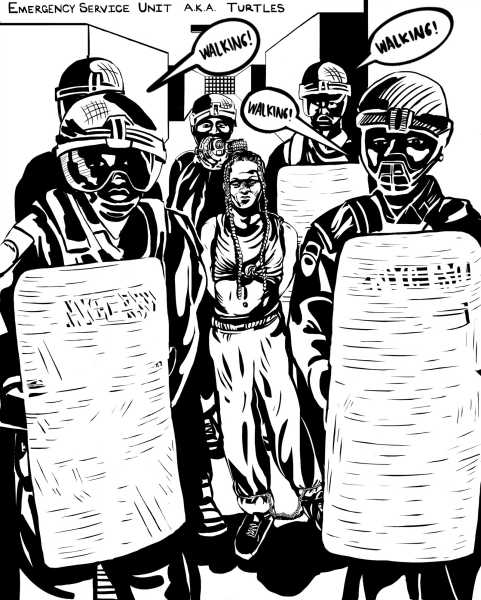

Once in a while, heavily armed “Turtles” ordered us librarians to step aside as they marched through. This unit was escorting a transgender woman while a correctional officer filmed everything.

In 2022, a task force convened by the Board of Correction said that the D.O.C. often put trans people in harm’s way by housing them in units that do not match their gender identity. Many experienced sexual violence.

I could only imagine how lonely my patrons felt when they didn’t speak the same languages as those around them. Our books became their main sources of entertainment and escape.

An artist on the fifth floor made amazing sculptures out of soap and coffee grounds. We also met talented writers, origamists, and T-shirt designers.

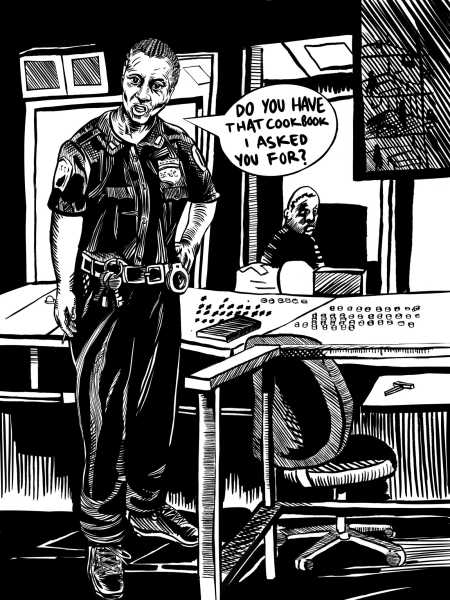

Most correctional officers didn’t talk to us or even make eye contact, but one always joked with us on our way out. She asked us to lend her books so she could pass the time on long shifts.

When I’d finish a shift at Rikers, my legs would be sore from standing all day. I’d think about all the people I’d talked to. I’d hope that I had made some small difference for them.

The words of a patron stuck with me: “At least you get to go home.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com