Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

A motorized wheelchair in the “off” position is about as movable as a heavy filing cabinet. The disobliging rider maximizes her gravity, pushing downward into her seat so as not to be dragged out of it. Police officers on either side struggle to get her down the hall. The rubber tires of her chair screech against the lustrous marble tile.

In black and white, this picture looks familiar. ADAPT, which stands for American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today, has been here before, many times. (ADAPT is similar in style to ACT UP, the grassroots group that forced the federal government to address the H.I.V./AIDS crisis.) In 1990, members of the organization famously rallied in Washington, D.C., to demand the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act. They ditched their wheelchairs, canes, and walkers, and lowered themselves onto the Capitol steps to crawl toward the building. In 2005, hundreds of members gathered to oppose Medicaid reductions and to demand home-based care. In 2017, they screamed “No cuts to Medicaid!” and blocked off the Capitol Rotunda, then parked themselves outside Senator Mitch McConnell’s office until the police carried them away.

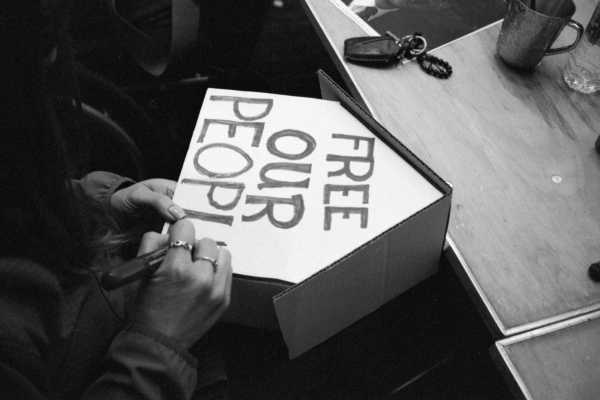

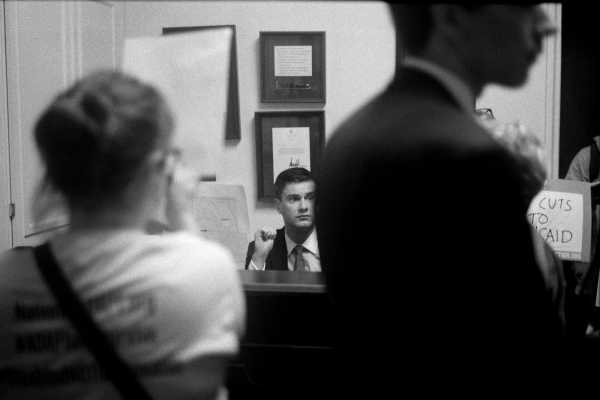

Last week, around seventy members from across the United States returned to the Capitol to protest the Republicans’ debt-ceiling budget bill. The legislation would nearly halve the Section 8 housing-voucher program, impose work requirements and administrative burdens on poor people covered by Medicaid, shut down Social Security field offices, and remove hundreds of thousands of poor children from Head Start education. Some of these changes would directly affect disabled people; others wouldn’t. Taken together, they constitute an historic assault on the social safety net. Activists with ADAPT, wearing transparent rain ponchos and house-shaped cardboard hats marked up with slogans (“Housing Not Guns,” “Free Our People”), lined the hallway outside the district office of House Speaker Kevin McCarthy. A group of them, many of whom were in wheelchairs, forced their way in and refused to leave. The Capitol police arrested fourteen people, including Rhoda Gibson, from the ADAPT chapter in Massachusetts. “They’re cutting so much,” she told me. “And Trump basically gave to the rich and stole from the poor.” (Neither McCarthy nor the Capitol Police responded to my questions.)

Perhaps because G.O.P. budget-slashing is commonplace, and perhaps because righteous demonstrations are, too, the latest ADAPT action got no press. The protesters were, however, memorialized on film. Nolan Trowe, the twenty-nine-year-old photographer who made these images—of a caravan of people in wheelchairs zooming past a gleaming police car, of a spiral-haired woman’s defiant stare as she’s forcibly moved through a doorway—is himself disabled. He was mostly paralyzed from the waist down in a cliff-diving accident in 2016 and moved from California to New York for graduate school. He took up photography and began to document a community he never expected to be a part of. “The cool thing about the disability community is that it’s so nebulous—anyone at any time can become disabled,” he told me.

Trowe often shoots from his wheelchair, a vantage point that privileges “elbows, buttocks, feet, and hands clutching phones.” He has photographed disabled friends in the New York City subway to show the system’s failings: only twenty-seven per cent of the stations are fully accessible. He has cast his own changed body in Super 8 reels about love. His photographs of ADAPT were his first of a “very political” nature, he told me. “People always look at the disability community as fragile and weak, but to see people out there, not giving a shit if the cops are roughing them up—to have so much power and grace in the face of all that—it was the first time I really felt like people were not just standing up for their rights, but my rights at the same time.”

A photographer named Tom Olin, who has covered ADAPT and the larger disability-rights movement since the nineteen-eighties, gave Trowe the idea of joining the protest last week. Seeing Olin there, Trowe felt a sense of inheritance, of “the old guard having to turn over to younger folks.” It’s emotional to look at their pictures side by side—the same grayscale contours, the same police, the same columns of wheelchairs, and the same exceedingly modest appeals on handmade signs. “We were demanding no cuts to Medicaid, no cuts to housing,” Gibson, the activist from Massachusetts, said. “How can you do that to people that are just trying to survive?” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com