When I was seven or eight years old, my mother’s father, Gene Ellis, bought a large pontoon boat, which he docked at a remote cove on Kaw Lake, not far from the small town where we lived, Ponca City, Oklahoma. My grandparents’ house was on Monument Road. A short walk from their gravel drive brought you to the iron gates of the Marland Mansion, the former estate of E. W. Marland, the oil tycoon who’d done more than anyone to shape Ponca City’s history. In the nineteen-twenties, before getting outfoxed by J. P. Morgan, Jr., and losing control of his company, he’d controlled more than ten per cent of the world’s known petroleum reserves. Later, in the thirties, he was a congressman and governor of Oklahoma.

Marland was long dead by the time I was born, but the company he founded, which became Conoco, was still our town’s largest employer. It was also the reason so many of my friends had to move away to Houston—because their parents were transferred there. The jobs were leaking away, not quickly, but quickly enough that you felt it.

For the next year or so, when the weather was warm, we were often on the lake, amid sunscreen and potato chips. Northern Oklahoma on a pontoon boat may not be what you picture when you think of a boating idyll. At Kaw Lake, the vibe was intensely landlocked. Ramshackle piers with tall grass growing alongside them. I have mostly good memories.

Once, it’s true, I missed the step off the dock and plunged straight down into the water, too startled to close my eyes. That had been scary, but the water of Kaw Lake always fascinated me. I’d heard that when the Corps of Engineers dammed the reservoir many years ago, an entire town, Kaw City, had been submerged. (This was true.) Whenever I swam in the lake, I half expected fingers to seize me by the ankles and pull me down to the drowned city, where I’d be lost to the sun and air.

I’d never known my grandfather to show any interest in boating, but, even at seven or eight, I understood that this was how he did things, with an impulsiveness so decisive and so laconic that the whole question of premeditation seemed somehow beside the point. Explanations, generally speaking, ran counter to my grandfather’s mode of being. If he had an idea about how to farm pigs more efficiently, he became a pig farmer. If he wanted to fly, he bought an airplane. Was there a boat he liked? Let’s hit the water. Why would someone need to know what he was thinking, when anyone could see what he was doing?

One day around this time, he showed up at our house with a trailer hauling a small circus carrousel. He’d seen it at a barbecue trade show and traded a smoker oven for it. Now it was a gift for my sister and me. It had a blue horse and a flying elephant. It had candy-striped poles. When they finally got it installed, it took up half the back patio. It played tinny music. If he ever told anyone what possessed him to acquire it, the report never got to me.

The author’s grandfather Gene with an unknown friend, in the spring of 1943.

Gene was born in 1920. He grew up on a farm in the deep nowhere of Red Rock, Oklahoma, where his family gritted out the Dust Bowl in a house they’d ordered from the Montgomery Ward catalogue. Windmill, chickens, faded laundry on a line. The land had belonged to the Otoe-Missouria tribe—that is, the tribe was forcibly resettled there—before the government broke up the reservations in the eighteen-nineties; it was still largely surrounded by Otoe-Missouria allotments. During the war, Gene trained as a pilot with the Navy. The fighting stopped before he was sent overseas. Like many men of his generation, he left the military determined that no one would ever again tell him what to do, a determination that in my grandfather’s case cannot have lain too far below the surface to begin with. Having always been both a little too rough and quite a bit too clever for his surroundings, he promptly moved back to them, returning to Red Rock with a new wife—Judy, my grandmother—and beginning a career of this and that. He tinkered with machines. He farmed. He hunted in the woods. He invented a new kind of feed mill and sold it around the country under the name Ellis Feed & Seed. He got elected mayor of Red Rock. He was brilliant, impatient, not infrequently drunk. He’d build beautiful knotty-pine cabinets for my grandmother’s kitchen. (Where had he learned do that with wood? He just knew.) Then he’d come home with ugly plastic furniture he hadn’t bothered to show her first.

My mother, the second of three children, grew up in a house with a gas pump at the end of the drive. Her pet raccoon out back. Gene’s Cessna in the field. From their house it was miles to the nearest paved road. My grandfather’s idea of a vacation was to pile the whole family into the car and drive for a week, then turn around and drive home. Roadside diners and motel pools. You got away, saw what was there, kept moving, went back.

My grandmother also came from Oklahoma, but she met my grandfather in California, during the war. He was in flight school, and she worked for Lockheed, building aircraft. A mutual friend introduced them. I have a box of letters he wrote to her after he left California for training in Texas. My grandmother saved the letters. There were hundreds, often more than one a day.

Dearest Brat,

How’s that for confidence—three days with no letter and tomorrow

(Sunday) will make four days and then I call you “dearest.”

They were wildly unalike. Judy had grown up in Oklahoma City. Her father, my great-grandfather, was a blacksmith. He was also an alcoholic. During the Depression, Judy had to drop out of school and take a job to bring money home. She worked at a soda counter. The Baileys weren’t among Oklahoma City’s élite—the opposite—but still, it was a city; you had culture, taste, refinement, even if only of the shop-window variety. You could hear music they didn’t play in the country. You could go dancing. You were close enough to civilization for some of it to rub off on you, if you wanted.

All her life, my grandmother had a quality of delicacy that never quite made sense in her surroundings. She was patient. She approached the world with sympathy and a kind of nervous gentleness, qualities whose frequency fell wholly outside my grandfather’s range of hearing, except that he loved them in her. She liked floral teacups, English novels, really anything English; I remember, as a small child, playing in her room while she watched “Masterpiece Theater.” She loved “All Creatures Great and Small.” I didn’t entirely know what England was, but it seemed to be a calming influence in the house on Monument Road, where there were elk heads on the walls, clumps of uprooted machinery on the breakfast table, and fierce tribal masks that my uncle sent home from New Guinea, where he lived. My grandmother had a turquoise bathtub, which struck me as deeply exotic, and when I was very small, three or four, I was sometimes allowed to take baths in it. She had sweet-smelling bath salts. I remember hearing her say “Crabtree and Evelyn.” To me, not understanding the words but catching the hint of what they meant to her, they sounded like portals to some larger, richer world.

The author’s mother and grandmother in their yard in Red Rock, Oklahoma, in 1949.

You can imagine, then, what a jolt it was for my grandmother to find herself in Red Rock after the war. In California, the world had looked full of possibility; now she was living in a cramped house in the middle of nowhere, with a husband who butchered his own deer carcasses. Who periodically vanished on three-day benders. In a county where the dirt roads turned impassable whenever it rained. She rolled up her sleeves, but it was hard. My grandfather had a brother. Family lore is unclear on what precisely was wrong with him—something with his brain, he’d had a high fever as a boy—but he’d drift over from the farm when my grandfather was away, and he behaved in ways that frightened my grandmother. Certainly he was threatening, probably sexually so. My mother and her siblings were taught to hide when he appeared. Finally my grandmother had to fight him off with a broom. After that, Gene paid him a visit, and he didn’t bother my grandmother again.

They moved to Ponca City in the nineteen-sixties, around the time my mother started high school. No doubt my grandmother had dreamed of the day—Ponca, with its twenty-five thousand souls, being the metropolis of legend where Red Rock was concerned—but, on my grandfather’s end, the change seems to have been characteristically impetuous. He was angry over the result of a school-board election? Something like that.

As Gene was getting tired of pig farming, he found that he was now extremely interested in barbecue, so he invented a kind of smoker oven and started a new company to sell it, along with a line of barbecue sauce and tubs of my grandmother’s chili spice. Judy kept the books. They opened a factory outside Ponca City. The company made a lot of money, and success or age or their combination mellowed my grandfather. He drank less. No doubt he still terrorized his employees; to my sister and me, he was a lamb. The year before, he’d shown us our first VCR tape, of a race from the Olympics: he pushed a button and suddenly the runners were wriggling backward, toward the starting line. On a trip to Germany, he got inspired by the construction of some little cottages he saw, and when he came back he built an astonishingly ornate playhouse in our backyard, across from the carrousel. It had levels. It had insulated walls.

That playhouse became the base for every game of my childhood, the command center for every neighborhood battle. Years later, when I was in junior high, my friends and I blacked out the windows and played Dungeons & Dragons by flashlight. Gene’s unpredictability, often a frightening quality for his own children, manifested for us only as a thrilling capacity for surprise.

One day in the spring of 1985, we spent the evening on the boat with my grandparents. I was nine. It must have been a Saturday, because it was the evening before Mother’s Day. The previous afternoon, my grandmother had taken my sister, who was five, shopping, and they bought a set of wind chimes for my mother, which we hung near the carrousel, on the back porch. That evening, on the boat, something felt off. Not alarmingly, but noticeably. It had to do with my grandfather. His voice was loud. He was drinking whiskey out of a teacup, and when he teased me about taking karate lessons (actually Tae Kwon Do, I said seriously), he did a mock hai-ya! kick from his seat that caught me on the hip; it was hard enough to bring tears to my eyes. But I didn’t think much of it. We puttered around the lake in the pontoon boat, wearing our life jackets, and then my father rowed my mother and my sister and me around the cove in the green rowboat that my grandparents kept at their dock.

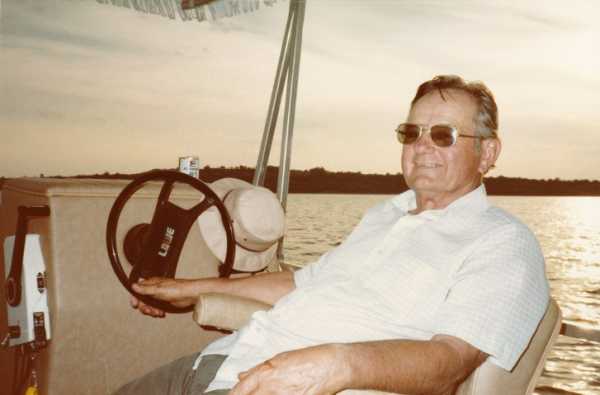

Gene, boating on Kaw Lake, in the summer of 1984.

When it was time for us to go home, my grandfather said he would stay at the lake a little longer. He wanted to set some fishing lines. My grandmother said she’d stay, too. My grandmother had driven us to the dock in her car, but not to worry: we could drive Judy’s car back to our house, and the two of them would pick it up later, on the way back to Monument Road. Simple enough. I was excited to ride home in my grandmother’s silver Ford, because it had a keypad lock, four numbered buttons in a horizontal row above the door handle, and I had never seen another car with a lock like that, and it was fun to tap in the combination.

That night, my mother woke up and noticed that the silver Ford was still in our driveway. But that wasn’t anything to worry over. My grandparents had probably just decided to go straight home after a long day on the water. We’d all been tired. My grandfather had looked especially tired, my mother thought. They would probably come for the car in the morning.

In the morning, the car was still in the driveway. Well—it was Sunday, Mother’s Day, a day to sleep in. Still no reason to worry. Just to be safe, my mother called Monument Road. No answer. It would be just like my grandfather, we all agreed, to have lit out on some trip without telling anyone. My parents decided to drive over to Monument to check whether anyone had been home.

We were sure it would come out all right. This was a temporary confusion, one we’d laugh about later—how dire the misunderstanding had felt, how harmless it had turned out to be.

My parents didn’t know how long they’d be gone, so they dropped my sister and me off at our other grandmother’s house, on Berkshire, a block away from home. Our other grandmother, Bonnie, my father’s mother, was at that time very sick with cancer. She had become, in her illness, deeply religious, religious in a way I understood to be intense and ultra-evangelical, and that morning she was being looked after by someone from her church, a woman whose name I can’t remember. Diana? All I remember is sitting at the counter in Bonnie’s kitchen and looking at a copy of the Ponca City News while the caretaker stood over the stove. Diana, or whatever her name was, explained to my sister and me that we were not worried enough about our missing grandparents. God was watching us, she said, and if we really loved Gene and Judy we would be praying for them. If they were dead, she told us, it was because we were not praying hard enough. God heard. She was making oatmeal, I think, as she said this? Stirring a steaming pot. After what seemed like a very long time, my father came, alone, and picked us up.

Back at our house, things were different. Some adults were there, in the living room. As we came through the front door, I had a glimpse of my aunt, my mother’s older sister, sitting on the couch with her feet curled under her, her face looking smeared and strange. My mother met us in the entryway and took us back to her bedroom. She knelt down and put her hands on our shoulders and told us that Grandma Judy was dead and that Papa Gene probably was, too. She said that my grandmother had drowned in the lake. They had found her body. They had not found my grandfather, but Robert Hardee, my aunt’s boyfriend, an artist, was back on the water with the Lake Patrol, and they were looking for him now.

Much later, my mother gave me a more complete picture of what had happened. My parents had driven to Monument Road and let themselves in by the back door. (My grandparents never locked their house.) Gene’s pickup wasn’t in the driveway, so they knew my grandparents weren’t home—the question was whether they’d been home at all since we left them the previous night. My mother thought, I’ll check Mom’s bathroom sink, and, if the sink is wet, I’ll know they were here this morning and just forgot about the car. The sink was dry. My mother called her sister and said, I think something is wrong. So my parents had driven with my aunt and Robert Hardee back to the cove. My grandfather’s truck was parked in the same place, and there was no sign of the rowboat. The four of them took the pontoon boat out to search the lake. My grandfather liked to use cutoff barbecue-sauce jugs as floats for his trotlines, and they saw one of these bobbing in the water, not connected to a line. Then my mother saw a speck of orange floating a long way off.

The speck was the color of a life jacket. It took a long time, my mother told me, to get close enough to see that the life jacket was attached to a body, and then it took a long time to get close enough to see whose body it was. My grandmother was floating facedown. Her hands were flexed as if she were clutching at something. Later, when they found my grandfather, he was not wearing a life jacket. (Of course not; he never did.) The coroner’s best guess was that he had fallen out of the rowboat and my grandmother had drowned trying to save him. He had been drinking, obviously, but there were certain signs, a bluishness of the torso, that suggested a heart attack, which might explain why he had fallen out of the boat. No one really knows what happened. Possibly my grandmother drowned with my grandfather, or possibly she died later, of hypothermia, trying to get back to shore.

I don’t remember my immediate reaction to the news that my grandparents were dead. I remember that I was calm. I was not as upset as the caretaker, the maybe-Diana, would have wanted. I said to myself, you will never see them again—my grandparents, whom I had seen several times a week since I was born—but I still felt, at the level of unconscious certainty, that this was a brief confusion, that there would be a happy ending. At some point the doorbell rang, and my friend Kyle was there with his dad. They had baseball gloves and a ball. They asked if I wanted to go to the field behind the school and throw the ball around. I said okay, thinking this was a little strange, because Kyle and I hadn’t really been friends since second grade, and now we were in third grade, so that seemed like a long time ago. Kyle lived down the street. Later, I realized that someone must have called his parents and asked them to take me out, to give me something to do, but at the time that didn’t occur to me. This just seemed like the next thing that was going to happen.

Kyle’s dad drove a tan truck. The old cab smelled like his tire shop, licorice sweet. There was a soft, red grease rag on the floor and, behind the seat (I knew), a battered tackle box. We drove to the elementary school and parked in the empty teachers’ lot. There were eight or ten elementary schools in Ponca City and most of them were named after Presidents, but ours was named after a local mortician, E. M. Trout. We were the Trout Tornadoes. E. M. Trout had been president of the school board. It occurs to me now (it didn’t then) that E. M. Trout & Sons, the funeral home he had founded, was probably where they were taking my grandmother. Kyle and his dad and I went behind the school and started throwing the ball. They had a bat so we started doing some hitting. It was a little odd, because I didn’t usually play baseball, but I seemed to have acquired a temporary ability to decide for myself how things would feel, so I decided it was fun to be there with them. Kyle’s dad pitched for us. I got some good hits.

I thought that what might have happened was that my grandparents had gone to London. They had gone to London on vacation a year or so earlier, and I remembered how much they liked it. They brought me back a handful of funny coins. My grandmother had always wanted to see Buckingham Palace. I had never been on an airplane, but I knew that to get to London you had to ride on one. In London, my grandparents went shopping for Burberry raincoats. They took pictures of each other in front of a red telephone booth. In her picture, my grandmother was wearing a raincoat and big glasses and smiling under her small cloud of dark gray hair. My grandfather was wearing red suspenders over his short-sleeved button-down shirt, and he was grinning in a private way, as if he were remembering the punch line of a joke. How was it possible to say someone was gone forever? We needed to check their closets. I would tell my mother to do it. We would find that their suitcases were gone.

Judy on the family boat on Kaw Lake, in the mid-eighties.

Forever would mean: no more walks with my grandmother to the gardens at the Pioneer Woman. No more rides with my grandfather on his green John Deere. No more sweet smell of bath salts. No more runners wriggling backward. No more carrousels. All this lost somehow, gone somewhere, pulled down to the city at the bottom of the sea.

Which was not London. My brain felt light and distant, but it was okay, I thought. The sky was huge and gray over the field. The wind was coming up. The school’s flagpole kept up a steady clanking. That night, I later learned, Robert Hardee, my aunt’s boyfriend, the artist, who had brought in my grandmother’s body, went back to the cove and performed some kind of Indian blessing for my grandparents. At our house, a storm blew in. Rain turned dark and glittery on the glass. We could hear the wind chimes ringing.

In my parents’ house in Oklahoma City, there is a painting by Robert Hardee of E. W. Marland’s castle on Monument Road, which was built between 1925 and 1928. A Renaissance palace, with light-brown sandstone walls and a crinkled red-tiled roof. Porches and gargoyles. Four roofed chimneys, which as a child I confused for prison towers. In the painting, there are nineteen-twenties sedans parked outside, as if for a party. A family in period clothes holds hands and walks toward the house.

The entrance to the Marland mansion lies through a pair of arched wooden doors, studded with iron. You pass through the heavy doors into the deeper shade of the vestibule and then through an elaborate archway, into the gloom of the grand foyer. The purpose of the foyer is perhaps less to embody any particular beauty than to tell you in unmistakable terms what kind of house this is. This is the kind of house where footsteps echo, where the quantity of stone, the depth of shadow, the massive height of the ceiling create an effect calculated less to please than to overwhelm. This is the kind of house where wall sconces take the shapes of satyrs. Where the stair rails terminate in wrought-iron dragon heads. Where the ceiling of the ballroom is coffered in gold leaf. The house is now a museum, and visitors repeat the familiar real-estate terms—forty-three thousand square feet, fifty-five rooms—as if they retained any meaning in the presence of a dining room whose pollard-oak panelling was cut “by special permission from the royal forests of England.” There is a secret room, concealed within the mansion’s third kitchen, where a door designed to look like a safe leads to a cavernous cellar in which whiskey was once kept hidden from Prohibition agents.

The house required vast sums not only to build but also to inhabit. E.W. and his wife, Lydie, who married in 1928, managed to live here for a little over two years. In 1931, they found they could no longer afford to heat the ballroom, to light the satyr-head sconces, to pay the large domestic staff necessary to man the three kitchens and keep the royal-oak panelling free from dust. They moved, first into the artist’s studio that E.W. had built on the estate, and then into the chauffeur’s cottage. They opened the mansion for special occasions. Political events, for instance. E.W. ran for Congress in 1932, and won. He ran for governor in 1934, on a platform of bringing the New Deal to Oklahoma. He won again. He turned the mansion into a political headquarters. He strode through the halls, signing papers. He threw an inaugural ball in the ballroom, under the gold leaf.

Once, when I was eleven or twelve years old, a therapist asked me if I had cried when my grandparents drowned. My parents had taken me to see this therapist, a child psychologist whose name I no longer remember, after I told them I felt nervous all the time, a true statement if not, clinically, a particularly interesting one. The therapist I recall as a sagging man in his late thirties with large clear aviator glasses and shaggy straw-colored hair. He wore baggy suits. His office was in a sort of prefab office park just outside town. I liked going to see him, because at the end of one fluorescent hallway in the medical suite there was a small refrigerator, and at the start of every session I was allowed to take out a Coke. After that, we sat in his office and talked, or else he gave me little tasks to perform and watched me do them. I had to arrange blocks in a certain way, or he’d show me how to draw triangles in a pattern that would create an infinite series of triangles, then tell me to “stop when it’s finished.” I didn’t see how any of this was supposed to help me feel less nervous. I didn’t see how questions about my grandparents were supposed to help me feel less nervous, either. They had died a long time ago, two years, and what did that have to do with anything? But I was used to being given quizzes and tasks, and I liked the Cokes, so mostly I went along and made things up only if I thought he wouldn’t understand the real answers.

I told him that I had cried when my grandparents drowned, but only alone, in the bathtub, where no one could see me.

This was one of the times when I made something up in order to seem understandable.

In fact, I had not cried when my grandparents drowned. In fact, I had not even felt sad when my grandparents drowned, at least not in the way I understood the word. What I felt was something else, a big, loose, empty feeling, and the right words for it didn’t seem to come from the language of emotions at all. I didn’t think I was wrong to feel this way, exactly. But I sensed that in some way it was a wrong answer, an answer that lay outside the interpretive paradigm we were meant to be working within, so without really thinking about it I told the therapist a story I thought he would know how to explain.

Note that I never imagined I might not understand what he was looking for. Only that it would be impossible for him—for other people, possibly for anyone—to understand me.

Where on earth, at eleven years old, had I gotten the idea that it was my job to be easily understood?

The author fishing on Kaw Lake, in 1984.

I spent a lot of time dreaming about leaving Ponca City. This, too, was something I had to be careful about expressing, because it could so easily be taken the wrong way. The problem wasn’t that I didn’t like Ponca City; it was simply that I did not belong there. Liking Ponca City, even loving it, as I sometimes thought I did, was a trap, because I could only relate to Ponca City from a kind of sideways angle, and, if I loved it too much, I might end up never finding the place where I was straightforwardly supposed to be. I was not supposed to be surrounded by churches. I was not supposed to have science teachers who believed in the gospel of creation, to hear commercial country music on every radio, to spend my life cruising down Fourteenth Street. I was not supposed to feel obscurely haunted by the half-ruined and mostly abandoned downtown, full of crumbling relics of the oil boom, or by the residential streets that bordered it, where what had once been the grand houses of Marland Oil lieutenants were now going to seed among old cars and trampolines.

I could see that these things suited other people, somehow fit the DNA of other people, often people I loved. But, when I imagined spending my life among them, I felt a wild desire to escape to the ends of the earth. When I was a little older, the place where I went to escape was the Marland mansion. I would drive there, past my grandparents’ old house, which had long since been sold, and park in the little parking lot beside the hedge garden. I had to sneak past the admissions desk in the gift shop, partly because I couldn’t afford the entrance fee, but also because I liked imagining I had the freedom of the place, that I could come and go as I pleased. I would walk straight across the grand foyer, stepping softly on the hard floor. I would climb the vaulted stone stair. The stair was dark. On the landing a pair of stone owls stood on pale columns. They looked down on you as you climbed. There were tiny red lights in the eyes of the owls. The owls’ eyes, in the dim stair, were four bright red points. For me, climbing the stair was like passing into another world. What my grandmother had found in the idea of England, I, having hardly ever left Oklahoma, found here. A place where things felt old. Where things were beautiful. The mansion made me feel a bit of what I’d felt when I discovered the nineteen-sixties book-club copy of “Poems of Byron, Keats, and Shelley” in my parents’ bookcase, a book I’d read so often it was now almost in tatters. I hadn’t known anything like that existed before. I wanted more things like it. The mansion was a link to the larger, richer world—the place where books like that came from.

Upstairs, I walked among the bedrooms, trying all the doors. Always, I visited Lydie’s room, which was my favorite in the mansion. Not because it was the grandest—it was modest compared with the spectacular public rooms downstairs—but because the quality of its loveliness was the hardest to define. The delicately carved limewood panelling around the walls had been contrived in such a way that there were no sharp corners anywhere in the room, only curves. The effect was serene, yet somehow also unnerving, as if the very fineness of the design blurred out something that might otherwise have been apparent.

At around this time, they brought Lydie’s statue back to the foyer. She’d ordered it destroyed, no one knows why, in the mid-nineteen-fifties, when she left Ponca City. The monument worker whom she hired to destroy it, Glen Gilchrist, took the pieces of the statue and buried them behind his barn, keeping the secret for decades. In the nineteen-nineties, it was rediscovered and pieced back together by art restorers. The reconstruction took two years.

The statue depicts Lydie at the age of twenty-five, in a thin dress. She has one hand on her hip and the other hand, which holds her hat, behind her back. She is standing with her left leg slightly in front of her right, and the skirt of her dress clings to her left thigh. The first time I encountered the statue, in the mansion’s foyer, I came close enough to see the pale lines crisscrossing Lydie’s white stone face where the sledgehammer struck it. I tried not to notice them. The hopes I had invested in the mansion, which I saw, impossibly, both as a means of escape and as a power capable of bringing lost things back, made it seem unwise, almost rude, to notice them. You see, I was still so young that I thought I should be looking at the statue. I should have been looking at the cracks.

This piece is adapted from “Impossible Owls: Essays,” published by FSG Originals.

Sourse: newyorker.com