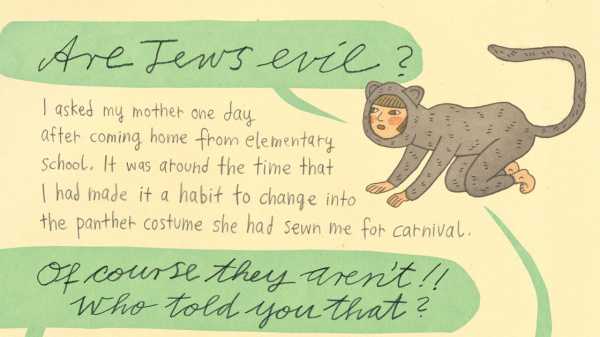

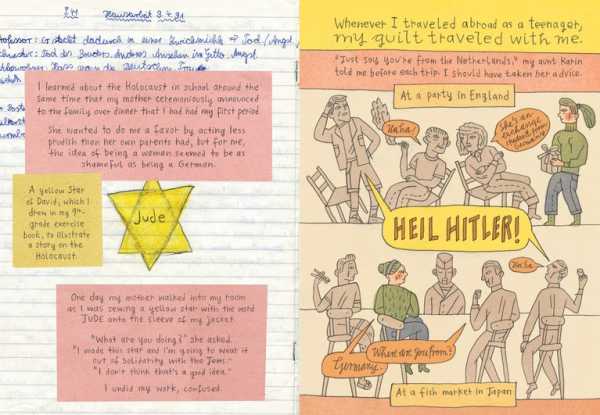

The artist Nora Krug was born decades after Nazi rule, but, growing up in Karlsruhe, Germany, she felt yoked to the sins of the Holocaust. This wasn’t just because the war was studied closely at school. There were shadows closer to home. Her grandparents had lived through the war, but never discussed it; her uncle had been a teen-age S.S. soldier when he died, in Italy. Krug has now lived abroad for almost two decades, in the U.S. and the U.K., and in the past few years she’s compiled drawings, photographs, and writing to make sense of her family’s past and her own German identity.

The resulting work, “Belonging” (Scribner), which will be published in the fall, has the informal feel and arresting candor of a diary. I recently talked to Krug about the process of mining her family’s communal memory, and what she has learned in her time away from Germany.

7

You’re known as an illustrator, and it’s what you teach. What drove you to write and draw a graphic memoir? Would you have tackled this if you could only write? If you could only draw?

I always begin my process by writing, but I don’t believe there is a hierarchy between the two mediums. They naturally complement each other. Combining visual and literary forms allowed me to jump between the present and the past, the factual and the poetic, the documentary and the imagined. My goal was not to translate the writing into images but to use pictures to give the reader a more emotional access into the narrative. For this particular book, it was especially important to weigh the text and the images carefully, in order to avoid a sense of sentimentality, or the impression that I was trying to create false sympathy for the Germans.

All that said, we’re currently considering producing an audio version of my book, and I look forward to thinking more about how the story can be told without images.

You grew up in Germany but have lived abroad for most of your adult life. Do you identify as German or German-American? What did you learn about your country once you left?

Of course, the country where you grow up shapes you most—culturally, historically, politically, emotionally. But what I associate most with Heimat (the German term for the place where you belong) is Germany as a site of childhood memories: the trips with my family to the countryside, the landscape of the Black Forest, our walks in the fields and vineyards. When I return to Germany now, I feel estranged from some of its culture: the directness with which people express their opinions; their constant fear of making mistakes; the lack of commitment toward one’s community, which results partly from the expectation that the government takes care of everyone. But there are also things I learned to appreciate only after I left: the willingness to discuss serious topics at length (without concluding the conversation prematurely with a joke, as is often the case in the U.S.); the commitment to social welfare, the protection of nature and animals, and a healthy legal system; and the beauty of the German language—one that is lacking, perhaps, in melody, but not in melancholy.

What was your German family’s reaction once you started asking questions about the Second World War? Who do you feel was most truthful, close relatives or strangers?

My parents and my aunt were supportive of the book from the start. Like me, they were eager to find out more, and they fully supported my research and my writing a book about our family and the war. They were raised at a time when Germany first started to confront its Nazi past, and, even though talking about your own family’s experience was an unspoken taboo during their childhood, the idea that it is our responsibility to face up to our past is deeply embedded in their psyches.

Did anyone refuse to talk, or give you answers you felt were inaccurate? If so, how did you deal with that?

Nobody refused to talk to me, even people I encountered during my field research, people I had never met before in my life. Inaccuracy was a problem when it came to some of the wartime stories that had been told over the course of generations in my family. For instance, there is a rumor that my maternal grandfather’s mother had been Jewish, and that that same grandfather had hidden his former employer, who was Jewish, in a garden shed during the war. I tried as much as I could to get to the bottom of those claims, but don’t believe that they are true. I suspect that they were a by-product of the guilt my family felt after the war—stories that made living with the shame a little easier.

You have a young child—was that a factor in deciding to tackle this project? Are there German traditions you’ll be proud to pass on?

I knew long before my child was born that I needed to write this book. As a German among non-Germans, I felt a growing urge to move beyond the abstract, collective guilt I had come to feel. Part of our German identity is, of course, its Nazi heritage. I want my daughter to grow up with the same sense of responsibility, but without the paralyzing guilt.

“Pride” is a word I shy away from as a German, but of course I want my daughter to live with a sense of German identity. There is a whole cultural heritage that was lost because the Nazis largely misappropriated it—old folk songs from the nineteenth and eighteenth centuries, for instance, that we were never taught at school. Many of those songs convey a notion of belonging, and emphasize the importance of old values such as steadfastness and faithfulness, a love for nature, the ability to accept death as part of life. Growing up without this heritage as an emotional anchor can leave you feeling utterly disoriented. I play these songs to my daughter regularly, and she sings along. I hope she always will.

You talk in the book about learning, in school, about American cultural identity. Living in the U.S., how did you relate to that identity? Was it appealing?

In German, we have a word called Zusammengehörigkeitsgefühl, meaning the sense of identifying with a larger group with which you share the same values and ideas. As I write in my book, we grew up using this word only to describe American cultural identity, but never our own, because the notion of believing in an idea bigger than yourself felt too close to what our people had aspired to under the Nazi regime.

A lot of Germans feel critical toward the way America expresses its sense of national pride, but they forget that a country as large as the U.S.—that consists of so many different cultures, political perspectives, and religious systems—could never exist without the belief in such an overarching idea, as utopian as it may seem. [For myself,] as a German moving to the U.S., the prospect of cultural belonging held a particular appeal. Obviously, the U.S. has arrived at its own moment of identity crisis, and the question of whether we’ll learn from the past—our own and that of other countries—seems more pressing than ever before.

Sourse: newyorker.com