Between the covers of all the cookbooks published each year, there are more recipes than it is humanly possible to make—it would take a lifetime of daily dinner parties to make it through October’s releases alone. I know I’ll never cook everything I want to cook, let alone read everything I want to read, so picking the best food books of the year comes with an inevitable asterisk: my teetering to-be-read pile has more than a few titles that I have a feeling ought to be on this list, like Rachel Herz’s pop-science explainer “Why You Eat What You Eat,” the chef Edward Lee’s travelogue-cum-cookbook “Buttermilk Graffiti,” and “The Donut King,” Ted Ngoy’s memoir of his path from Cambodian refugee to the head of a Southern California donut empire, and then precipitously downward from there.

2018 in Review

New Yorker writers reflect on the year’s best.

Among what I did read (and cook from) this year, my favorites are the books that treat what we make and what we consume not as an escape (or, as with diet books and other packaged scoldings, a problem to be solved) but as a prism, a way of deepening our understanding of the world. Every time we take a bite, we’re engaging with history, science, and culture. These books wrap that truth in beauty, or something sort of like it.

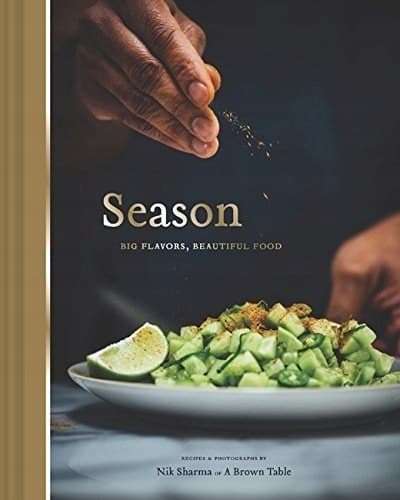

“Season: Big Flavors, Beautiful Food,” by Nik Sharma

Sharma has honed his distinctive culinary style over the years on his blog, “A Brown Table,” and in his regular column in the San Francisco Chronicle. The recipes in his exceptional first cookbook are simple enough for novice cooks but rise to thrilling and unexpected places through Sharma’s savvy use of a spice pantry that draws from around the globe. I keep coming back to his flavor combinations—lately, a savory tea soup featuring Lapsang souchong steeped with ginger, cloves, and mushrooms, in which ribbons of yellow squash wave like flashes of sunlight. The volume’s recipes, and gorgeously moody photos, use food to gracefully tell Sharma’s own story: India to America, Ohio to Washington, D.C., to California, hard science to culinaria, solitude to a loving family with his husband, whose Appalachian roots introduced even more flavors to Sharma’s already formidable arsenal.

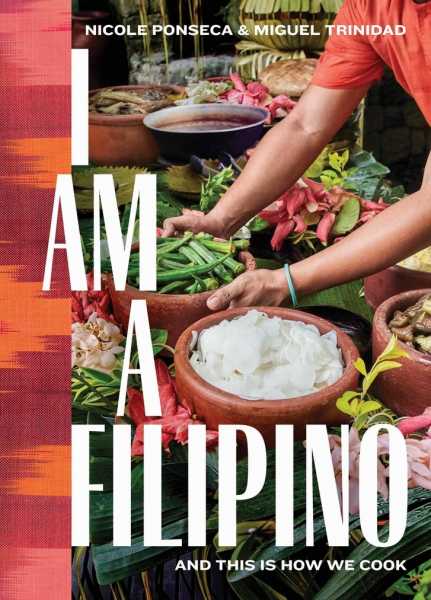

“I Am a Filipino: And This Is How We Cook,” by Nicole Ponseca and Miguel Trinidad

Filipino cooking is among the brightest, sweetest, sourest, and funkiest of world cuisines; by comparison, almost any other food seems bland. Ponseca and Trinidad, the proprietors of the excellent Manhattan restaurants Maharlika and Jeepney, weave together threads of Filipino history, culture, and diasporic traditions into an exuberant gastronomic manifesto. It’s a brilliant cookbook that doubles as an important work of cultural scholarship, or maybe an important work of cultural scholarship that doubles as a brilliant cookbook—from foundational recipes like pinakurat (a sweet-tart-hot condiment made with fruit, fish sauce, chiles, and vinegar) to a rainbow of adobo styles, meats, and methods.

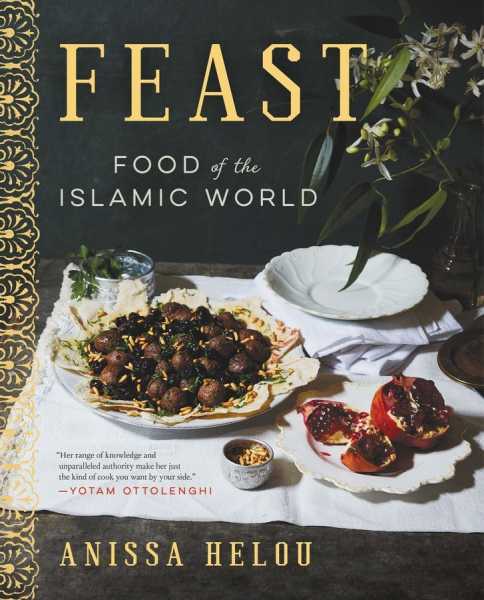

“Feast: Food of the Islamic World,” by Anissa Helou

Helou is one of the great chroniclers of Middle Eastern cuisine, but the recipes in this book are bounded by religion, not geography. They span not only the Arab world and north Mediterranean but Asia and Africa, telling a story of migration, conversion, and conquest, and the effects of these forces on the eating and preparing of food. The book is breathtaking in its scope—and beautifully cookable, too, with clear explanations of ingredients and techniques, and reader-friendly adaptations of traditional recipes, like a Tunisian fish stew sweetened with quince, a tart Iranian meatball soup swirled with pomegranate molasses, or gado-gado, the Indonesian salad made of a wild array of vegetables, crisps, eggs, potatoes, and other delectables, served with a luscious peanut dressing.

“Hippie Food,” by Jonathan Kauffman

There is no new food trend under the sun. Kauffman’s tack-smart and phenomenally entertaining history of the radical food movements of the nineteen-sixties and seventies places our current avocado-and-ancient-grains moment in its proper context: one of activists, gurus, and back-to-the-landers who rebelled against postwar systems of growing, cooking, and eating food, bringing then-radical ingredients like tofu, brown rice, granola, yogurt, and dreaded carob into the American mainstream.

“How to Eat a Peach,” by Diana Henry

This is the eleventh cookbook by Henry, a culinary icon in Britain, and it tackles a subject that most books fail to address: the art of putting together menus. Pairing a main dish with simpatico sides and desserts can inspire terror in the home cook (especially, Lord help us, when planning dinner parties). Henry’s fine culinary taste (particularly her fluency with vegetables—leeks with Breton vinaigrette, Korean cucumber kimchi, a pistachio pesto spooned over fresh asparagus) and sparkling-wine prose make it all sting a little less. She writes that she’s been composing fantasy menus since her teen years, and these recipes—elegant and unfussy, drawing on fresh produce and a gorgeous global pantry—have exactly the sort of confidence that I look for in times of kitchen crisis.

“We Fed an Island: The True Story of Rebuilding Puerto Rico, One Meal at a Time,” by José Andrés with Richard Wolffe

In the fifteen months since Hurricane Maria tore through Puerto Rico, dealing unprecedented ecological damage and leading to almost three thousand deaths, the island has received infuriatingly little from the federal government. By contrast, in the days and weeks after the storm, the Washington, D.C.,-based chef (and frequent Donald Trump antagonist) José Andrés managed to rally the ingredients, tools, and labor to feed more than three million meals to Puerto Ricans in need—a feat of large-scale selflessness that raised the bar for what a celebrity chef can do, and earned a Nobel Peace Prize nomination. Then he wrote and published an entire book about how he pulled it off. The book’s damn good, too.

“Provisions: The Roots of Caribbean Cooking—150 Vegetarian Recipes,” by Michelle Rousseau and Suzanne Rousseau

“The story of Caribbean food cannot be told without telling the story of Caribbean women,” the sisters Michelle and Suzanne Rousseau write. Their book is an ode to culinary matriarchs and a welcome reconsideration of the culinary legacy of the Caribbean, which is too often caricatured as a cuisine of simplistic tourist staples. The Rousseaus chronicle how the region’s history of colonization and slavery extends into the present, shaping the Afro-Arabic-Asian-Caribbean ingredients and techniques that form the foundation of their cuisine. (The book’s vegetarian focus is a nod to the limited diets of enslaved Africans brought to the islands.) I learned a tremendous amount reading this book, and I love its recipes—dishes like a raw pak choi salad with crunchy ramen noodles, and fiery pickles of cucumbers and hot peppers are already staples in my kitchen.

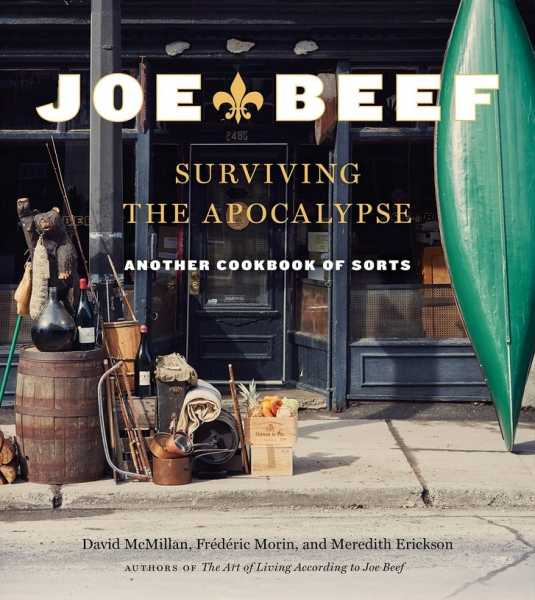

“Joe Beef: Surviving the Apocalypse: Another Cookbook of Sorts,” by David McMillan, Frédéric Morin, and Meredith Erickson

The first Joe Beef cookbook is one of my favorite food books of all time—a weird, obsessive scrapbook of high-end gluttonous ephemera, wrapped around recipes that would be deranged if they weren’t so ingenius. In their second book, the Quebecois chefs McMillan and Morin are still at it. They’re the sort of people who publish “Potage Télépathique,” a buttery turnip soup that pays homage to their claim to reading each other’s minds, just a few pages past a recipe for calf brains served atop Indian-spiced peas—“Brains over Matar” (get it?). The “Apocalypse” of the title is a vague and compelling creative conceit: everything is ending, so why not make a towering savory confection of smoked whitefish salad garlanded with pastry swans? Or not. As the headnote points out, it’s quite an ordeal: “David says, ‘Just don’t do it.’ ”

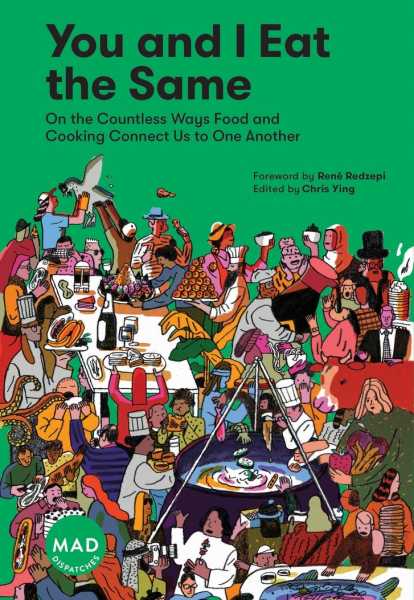

“You and I Eat the Same,” edited by Chris Ying

This is an argument disguised as an anthology, built around the straightforward thesis of its title. It’s the sort of platitude that could collapse into a gooey mess of kumbaya, but these essays—by an all-star lineup of writers, including Osayi Endolyn, on fried chicken, and the scientist Arielle Johnson, on what it means to cook with fire—are concrete and eye-opening, touching on how food affects (and is affected by) migration, immigration, war, flight, history, and home. The book is published by MAD, a culinary nonprofit organization affiliated with the ultra-famous Copenhagen restaurant Noma; two of the essays are by Noma’s René Redzepi and David Zilber, the co-authors of “The Noma Guide to Fermentation,” another of my favorite books of the year.

Sourse: newyorker.com