Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

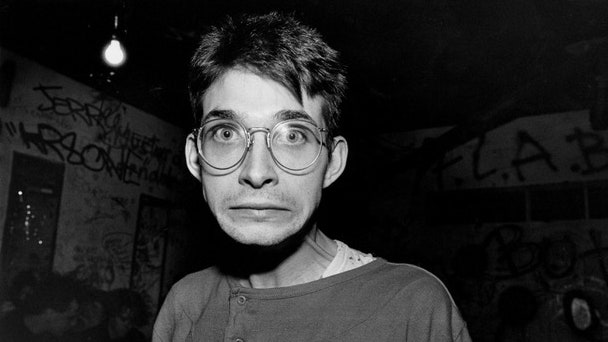

This past Tuesday, May 7th, the engineer, producer, and musician Steve Albini died, of a heart attack, at his home in Chicago, where he has run a recording studio, Electrical Audio, since 1997. Albini was sixty-one. It’s almost impossible to quantify his impact on underground music. It’s also almost impossible to quantify, in a more literal way, the precise number of records he worked on, though he once estimated it to be in the thousands. When I was a teen-ager coming of age, in the late nineties, “Steve Albini” was more of an idea than a person, a pair of words—melodious, mysterious—stamped onto every other record I loved or was terrified by. He led two heavy and careening punk-rock bands (Big Black and Shellac), but his discography as a producer and engineer is stunning: Nirvana’s “In Utero,” PJ Harvey’s “Rid of Me,” the Pixies’ “Surfer Rosa,” Joanna Newsom’s “Ys,” Palace Music’s “Viva Last Blues.” Albini was sought after for his ability to demand and protect spontaneity in recorded music, a pursuit that sometimes felt at odds with evolving technology, and sometimes felt at odds with the idea of recording itself. Albini never made an album that seemed as though it were happening somewhere else, at some other time. These were not fixed and polished documents. Everything he worked on felt raw, urgent, instantaneous, live; it was always occurring for the first time, just then, just for you.

My sense is that Albini thought of himself as a shepherd, and regarded the work with a corresponding humility. He was not a sentimental guy. He was snide and withering and judgmental, sometimes grossly so. He could be incredibly mean. The line between righteous provocation and poisonous needling is thin, and Albini occasionally misjudged it. (In 1987, he formed a band called Rapeman, which dissolved two years later; he once complained online about an encounter with the rap group Odd Future, repeating a racist word, and later excused it by saying, “I was simply describing their behavior and language.”) Sanctimony and spitefulness can be an acidic combination, and, in 2021, Albini underwent a kind of spiritual reckoning, posting an apology of sorts to Twitter: “A lot of things I said and did from an ignorant position of comfort and privilege are clearly awful and I regret them,” he wrote. “Life is hard on everybody and there’s no excuse for making it harder. I’ve got the easiest job on earth, I’m a straight white dude, fuck me if I can’t make space for everybody else.” In an excellent and wide-ranging interview with Jeremy Gordon, published in the Guardian last summer, Albini again copped to his mistakes. He knew enough not to ask for forgiveness: “I’m embarrassed by it, and I don’t expect any grace from anybody about that,” he said.

I don’t know that Albini deserves our generosity on these matters, but one gets the sense that, as a younger man, he was driven by a kind of crazed frustration with polite society, all the ways in which we have defanged and neutered ourselves. In the end, that anger is also what fuelled his work. Albini would probably have found it unbearably pretentious of me to drop the word “vocation”—he didn’t even like “producer,” and avoided it assiduously—but no other engineer was quite as attuned, in an almost metaphysical way, to the humanity of recorded music, its senselessness and magic, the truths it could crystallize or reflect back at us. The creation and consumption of music serves no plain biological purpose—how utterly reasonless and inexplicable that we do this at all! How beautiful! Albini was a ferocious champion of preserving that purity, awake to all the ways in which our sharpest and best instincts are endlessly and tediously eroded by corporate machinery, by external meddling, by our own fears and insecurities and self-regard. He was not polite about his policing of those forces. They received no quarter in his studio. He seemed to despise record labels, especially the big ones. He once told Nirvana that he wanted to be “paid like a plumber”—meaning he didn’t want anything to do with points or percentages, just a flat fee for services rendered. He remained opposed to the monetization and degradation of creative spirit. It’s easy to deride this sort of staunch incorruptibility as a Gen X relic, incompatible with the way we live and consume now, but I find it awesome. Whatever Albini did in that studio—the way he placed a microphone; the particular manner in which he tracked a snare drum, so dry and testy, so good—was focussed on cutting through bullshit. Who does that anymore? We Auto-Tune; we filter. We blur reality until we don’t know which end is up.

Recently, the entire typewritten letter that Albini sent Nirvana prior to the “In Utero” sessions has been making the rounds on social media. Integrity is an undervalued and under-considered quality in art these days; somehow it has come to seem childish to insist on ethics while navigating the marketplace. I can’t help but marvel at Albini’s certitude on this front. When Nirvana made “In Utero,” in the winter of 1993, they were one of the biggest and most important bands in the world. Albini didn’t give a fuck. He was interested in making music that was free, as he wrote to the band, of “click tracks, computers, automated mixes, gates, samplers and sequencers.” He believed in a kind of lunatic freneticism, an immediacy, the notion that the more a song was worried over, the less potent it became. “If a record takes more than a week to make, somebody’s fucking up” is how he described it. Mostly, he didn’t want to genuflect to boneheads in suits who didn’t know anything about punk rock. “If, instead, you might find yourselves in the position of being temporarily indulged by the record company, only to have them yank the chain at some point (hassling you to rework songs/sequences/production, calling-in hired guns to ‘sweeten’ your record, turning the whole thing over to some remix jockey, whatever . . .) then you’re in for a bummer and I want no part of it.” There was no amount of money or fame that could entice Albini to compromise. How many artists can we still say that about? “The record company will expect me to ask for a point or a point and a half. If we assume three million sales, that works out to 400,000 dollars or so. There’s no fucking way I would ever take that much money. I wouldn’t be able to sleep,” he wrote. (“In Utero” has sold at least fifteen million copies.)

It’s tempting to call Albini a misanthrope, and certainly he had tendencies toward a kind of knee-jerk cynicism. But there is evidence of deep love and delight in his life, too. (He was married to the filmmaker Heather Whinna; in a charming food diary he wrote for New York, in 2018, he reveals himself to be a feisty gardener, an excellent cook, a formidable poker player, and a connoisseur of something called “fluffy” coffee, or a cappuccino with cinnamon and maple syrup. He also said that he happily prepares his wife whatever she wants for dinner each night: “I’m not picky, and I like making food for other people.”) The evening after I learned of Albini’s death, I took to Instagram—as one does—to post a photo of “The Magnolia Electric Co.,” an Albini-produced album by Songs: Ohia, released in 2003. Songs: Ohia was then the alias of the musician Jason Molina, who died young, in 2013, at age thirty-nine, from complications due to alcoholism. It’s a formative record in my life, heavy and deep and flawlessly recorded, which is to say that when I put it on, there’s nothing in the way. No distance between me—between any listener, anywhere—and Molina. Because of that, it feels like a portal to another sphere, a lifeline, a hand to hold in the night. It sounds like air and starlight. Molina’s voice is plaintive, desperate, close. Art like this is inherently benevolent. It is there to help us. Albini could be caustic, often combative, but perhaps he was simply saving all of his love and care for this one gesture. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com