Stuff is a problem. Just ask the wellness experts. “Clutter is bad” is a mantra so ubiquitous that I sometimes think we are all living in the wake of that Steve Jobs portrait from 1982: black turtleneck, hi-fi, bare floors, the Zen master of simplicity. We associate success with the same streamlined visuals that we expect from our highways and electrical appliances. We look for a slickness that keeps us moving to a better place, when, really, the better place is right here, with things that we can touch and feel. Suzanne Bocanegra’s art is an antidote to the history-free, prepackaged world that threatens every day to overwhelm us. Her work is also beautiful.

Bocanegra is often referred to as an artist who crosses boundaries, which gets at what she does but maybe also insults artists, who are by definition boundary-crossers. She has worked as a painter and a sculptor and in costume design, but she is probably best known for performance pieces that she refers to as her “artist talks”—the quotation marks invoking her version of the age-old presentation of an artist with slides. They are theatrical performances of the classic slide-show-and-lecture variety, along the lines of Spalding Gray’s monologues, though, in Bocanegra’s version, an actor, rather than the artist herself, takes the stage and plays the part of Bocanegra. (Last year, Lili Taylor performed “FarmHouse/Whorehouse”; in 2013, Frances McDormand performed “Bodycast”; in 2010, Paul Lazar appeared in “When a Priest Marries a Witch.”) During these performances, Bocanegra sits to the side of the stage, reading into a microphone that transmits her voice to the ear of the performer playing her. Last summer, all three of Bocanegra’s artist talks were performed in a daylong marathon, at Bard College. At the end, when her three avatars took a bow, the real Bocanegra was in awe. “I liked that,” she said.

Her new solo exhibition, which is at Philadelphia’s Fabric Workshop and Museum through February 17th, is titled “Poorly Watched Girls.” It’s a good idea to start at the top floor of the workshop, where Bocanegra has made sets and costumes for “La Fille Mal Gardée,” the French ballet that is the namesake for the show. Possibly the second-oldest work in the modern ballet canon, “La Fille” was seen as radical in its day, because it is a love story between two mere peasants. (It premièred in 1789, less than two weeks before the Bastille was stormed, to give you an idea of precisely how revolutionary it was.) Bocanegra’s peasant costumes are really assemblages. Two mannequins greet visitors, and they are not so much clothed as they are sculpted from a thousand talismans—items that feel precious even if you aren’t precisely certain what they are. One character wears a piece of a sweater, a part of a tea towel, a child’s drawing, a faded picture of a seventeenth-century English cabinet, and swathes of cut-up watercolor paintings, and it has sticks of bamboo for arms. The other figure wears a collar fashioned from chicken wire and papier-mâché derived from the New York Times arts section, adorned with a pendant replication of a John Marin painting of an island in Penobscot Bay. You would be afraid to try on any of these ensembles, partly because it would be impossible, and partly because they feel haunted.

Haunted by badly wired power and by dreams and realizations that are double-crossed and short-circuited, the storyline of the ballet involves a girl who is engaged to a man she does not love. One day, her mother falls asleep at the spinning wheel, and the girl manages to slip away to marry her true love: a happy ending in an exhibition that concentrates on how women are managed, thwarted, or worse. “All of these are about women who have no power, who need to be guarded, who need to be watched,” Bocanegra said, about the exhibition pieces, on a press tour last week. “It’s like Superman guarding Lois Lane. We never get tired of it.” One thing that makes Bocanegra’s work so smart and powerful in dealing with the relentless characterizations of women as lost and misguided and in need of one kind of surveillance or another is her deft use of farce and satire. In this case, she comically juxtaposes high culture’s fetishizing of rural life with the drudgery of rural reality, simultaneously skewering the trends of high culture in both contemporary America and eighteenth-century France.

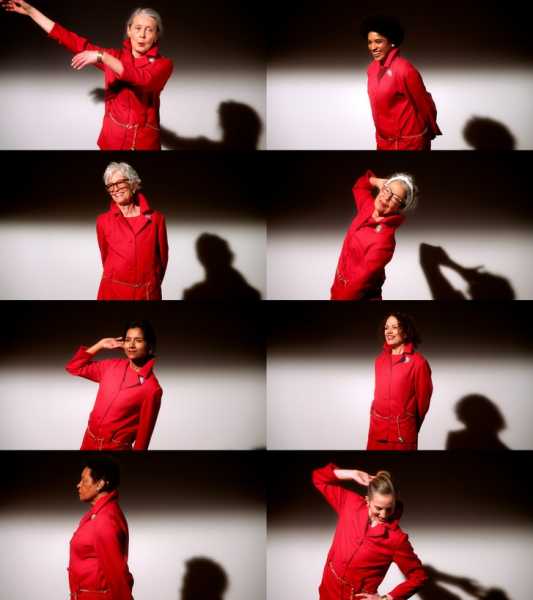

In “Valley,” eight women reënact Judy Garland’s wardrobe test for “Valley of the Dolls.”

Photograph Courtesy Suzanne Bocanegra

On the next floor down is a video montage by Bocanegra, titled “Valley,” which takes as its starting point the wardrobe tests for “Valley of the Dolls”—the 1967 film, in which Judy Garland was initially cast as Helen Lawson. The story of what happened to Garland on the film’s set, two years before she died from an overdose, is tragic, to say the least. Reports describe the studio medicating the child star to her end, and all that remains of Garland’s involvement in “Valley of the Dolls” is the wardrobe test. Garland moves and turns at the bidding of a barely seen director, saying a few nervous things. In “Valley,” Bocanegra redeems the actress by casting “eight strong women I admire” (according to the wall text): Anne Carson, Deborah Hay, Joan Jonas, Alicia Hall Moran, Tanya Selvaratnam, Kate Valk, Carrie Mae Weems, and Wendy Whelan. For each of Bocanegra’s Judys, designers at the Fabric Workshop and Museum re-created Garland’s now legendary suits from her last concerts, performed in the two years between when she left the film—when she quit, was fired, or some dark combination of the two—and when she died. And so, when we enter the Fabric Workshop’s long, dark gallery, eight videos run simultaneously—eight women performing Judy, who is herself not exactly performing but being a particularly vulnerable Judy. Wearing an earpiece that neatly refers to Bocanegra’s “artist talks,” each actress speaks Judy’s words, moves as Judy moved. If you think about Judith Butler’s famous take on Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology—“One is not simply a body, but, in some very keen sense, one does one’s body . . .”—then you can stand there for a long time, feeling mesmerized the way you do when in a dressing room, when you look into an infinity of repeating mirrors, enactment on enactment, an operatic Greek chorus.

The visit builds to the two pieces on the first floor, one based on an opera, the other based on a few phrases that Bocanegra’s grandmother repeated through dementia, when Bocanegra, as a young girl, knew her: “Would you like some lemonade? My roses are so beautiful. Why won’t he give me money for my satchel?” The composer and singer Sara Nova wrote a song for voice and harpsichord from these three phrases, and the result is sad but thrilling. It’s performed by Nova in a peasant costume that Bocanegra designed—a bundle of sticks and roses attached precariously to her braided red hair, all of it glorifying the beauty of vulnerability.

In the last room of the exhibit is Bocanegra’s staging of “Dialogue of the Carmelites,” a nineteen-fifties opera based on the story of a French convent where the nuns are executed by anticlerical French revolutionaries. This piece works almost like a side altar for the show. The artist was (obviously) educated in a Catholic school. In a darkened room, we see a four-walled tableau of pages from “A Catholic Sisterhood of the United States,” a catalogue of religious orders for women. Each page is touched with embroidery. A piece composed by Bocanegra’s husband, David Lang, runs on a loop, like a sonic rosary. The chapel-like room is contemplative; the viewer reads what was expected of a nun in the fifties, what they took on, what they gave up, while guarded, while in religious costume. “Sewing, cooking and sacristy work are available for those not attracted to teaching or nursing,” according to the entry on the Franciscan Sisters of Our Lady of Perpetual Help, of Saint Louis, Missouri. “I was alone,” Caroline Shaw sings, and the room allows all the other rooms to form a collage in your head, to resonate, before returning you to the present, somehow renewed.

Sourse: newyorker.com