Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

In the literature of late twentieth-century cruising, its physical choreography stands out. David Wojnarowicz, in his 1991 memoir Close to the Knives, recounts exploring abandoned warehouses on Manhattan’s West Side, “weaving his way through shadows and corridors, catching a glimpse of a group of men in various stages of arousal at the back of a room.” Andrew Holleran, in his 1978 novel The Dancer of the Dance, depicts “dark clusters of people gathering in empty parking lots, around parked trucks, in alleys, worshiping Priapus under the summer moon.” And when Samuel Delaney brings his girlfriend to witness a sex scene at a Manhattan all-night movie theater, she notes in her memoir Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, “There are a lot of people walking around…”

Delaney’s 1999 memoir laments the closing of urban spaces where men, seeking other men, once came for anonymous sexual encounters. Broadly defined, “cruising” is the search for impersonal sex in public spaces—restrooms, parks, saunas, movie theaters. The practice has been around as long as cities have, and has traditionally been a response to taboos on certain kinds of sexual relations. “Exchanging brief glances or knowing nods at the urinal wall, tapping a foot, flicking away wads of crumpled toilet paper,” Alex Espinosa writes in Cruising: An Intimate History of a Radical Pastime (2019). “We developed ways to communicate in secret and coded languages because we had to.” In the 1960s and 1970s, cruising spots were listed in printed directories like Bob Damron’s Address Book, a self-published catalog of gay bars and “cruising zones” across the country and beyond. But after the AIDS epidemic and the disappearance of many urban cruising spaces due to sanitation and gentrification, the practice of the idea moved online.

There’s a palpable sense of nostalgia in Petite Mort: Reconlections of a Queer Public, a 2011 essay collection of writers and artists edited by Carlos Motta and Joshua Lubin-Levy. “Every conceivable option was there: laborers, delivery boys, salespeople, managers, tourists, random dads, and… well, you name it,” writes Aiken Forrett of the World Trade Center’s lower-level restroom. In the same collection, legal scholar Katherine Franke describes an “afterlife of homophobia” in which queer sex—following the decriminalization of “sodomy” in the 2003 Supreme Court case Lawrence v. Texas—has become not only legalized but privatized. Franke calls for a kind of rethinking: “It’s time to confront sex that is hygienic, that seeks to cleanse homosexuality of its obscenities.”

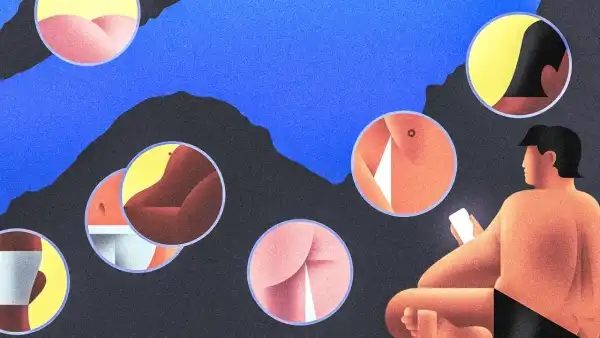

The emergence of Grindr, the first major dating app to use location-based technology, in 2009 marked the beginning of a new era in hookup culture. Its liberating potential—free sex available via phone—captured the imagination of both straight and queer people, and OkCupid, Tinder, Scruff, and Growlr soon began copying Grindr’s feed, which showed users’ proximity to one another. But what was initially perceived as a new freedom eventually became a form of labor: the effort of creating a sexually appealing profile using curated photos and a short bio; hours of scrolling. Today, Grindr may be the most popular LGBTQ social network, with over fourteen million monthly users, but it has also been accused of further pushing LGBTQ life into the private space—one study found that the number of LGBTQ bars in America declined by 36% between 2007 and 2019.

As the pursuit of sexual connection has become increasingly digital, a palpable yearning has emerged—not for the moral repression that gave rise to cruising, but for its qualities of anonymity and spontaneity. In a 2016 essay praising cruising, the writer Garth Greenwell wrote of spaces “where the radical potential of queerness still resides, a potential that has been largely erased from the mainstream, homonormative version of gay life.” It is in this context of nostalgia for something less predetermined that Sniffies.com began to gain popularity in 2018.

Sniffies bills itself as a “mapping app for gay, bi, trans, and just plain sex-curious people.” It’s accessed through a web browser. There’s no need to create a profile, upload photos, or even provide an email address. Open the app, sign in as an anonymous user, and you’ll get a real-time sexy map of your neighborhood. Sniff

Sourse: newyorker.com