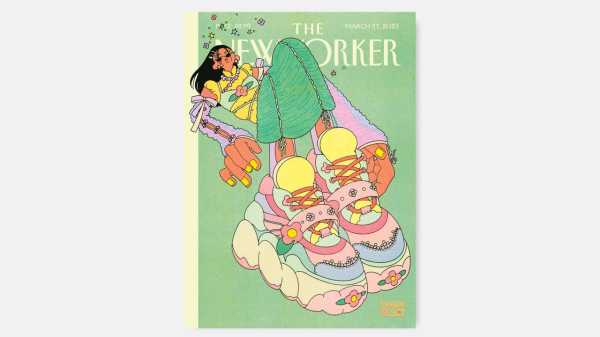

The cover of the March 27, 2023, Spring Style & Design Issue is by Sarula Bao, her first for the magazine. Bao’s image features bows, flower decals, and transparent sleeves—some of the design elements from the fashion world that excite her most. The chunky sneakers in the foreground are a familiar feature in her recent work, typifying the ways in which style so often takes the old and makes it new. I spoke with the artist about the ways in which fashion and design can engage people in conversation and community—and how to make that connection more accessible for all.

Some of your images have combined traditional Chinese garment styles, like hanfu, with chunky sneakers, reinterpretations of the nineties’ “dad shoes.” What’s most appealing to you about pairing disparate elements like these?

I love fashion that creates connections in culture, in history, in memory, in community. I love the way that everyone is experimenting with styles, drawing from American, European, and Chinese vintage and street fashion, as well as Japanese culture and anime, taking it all and mixing it together. Hanfu is the clothing of the Han ethnic people; recently, young Chinese people have been getting really into it, saying, “We’re interested in our culture,” and making it fashionable. I’ve seen a lot more hanfu on Chinese social media, and now it has spread to U.S. social media, too. And, beginning around 2020, chunky sneakers started to get really hot—also in East Asia—a callback to nineties street fashion, to Y2K fashion, Black street style. It’s these reinterpretations of old elements in new and creative ways that make me feel excited and energized.

Two examples from a recent series, Hanfu x Chunky Sneakers.

Which fashion designers have caught your eye?

There are so many: I really love Simone Rocha for her romantic style and combination of hard and soft elements. Celine Kwan has also been a big influence on me as well for her playful shapes and colors. I’ve also been enjoying the Sultry Virgin brand a lot, with their Y2K-inspired pieces.

When working on this piece, you produced a Riso print, a kind of screen printing made digitally, at the School of Visual Art’s RisoLAB. What’s so special about this technique, and why did you choose it?

I think that Riso is a really cool, really beautiful tool, because it combines the easy accessibility of what is essentially a copy machine with the quality of traditional printmaking, in an affordable way. Each color goes on individually, one at a time, and as a result you can experiment with three-, four-, or even five-color prints, mixing color on paper. When used as an art-making process, it creates that handmade quality: the grainy texture, the misalignments, the trademarks of traditional printmaking. And it’s so fast. It aligns with a lot of the things I care about when I’m making art.

To support yourself as an artist, you’ve had a number of jobs. When you chose to become an artist, was that something you anticipated?

Yes, because it’s all people talked about in art school. I was prepared to work multiple jobs after graduation. But I discovered that I don’t actually want to work as a freelance artist full time. I got stuck at home, drawing all day, and I didn’t have much of a schedule. The work came and went—either you get a lot at once and it’s way too much, or it trickles and there’s nothing at all. I was always stressed about my income and had to say yes to everything, because I didn’t know when the next job would come. I’d get a lot of assignments in February and in May, around Lunar New Year and A.A.P.I. month, often all at once. I really wanted the flexibility to say no if I needed to.

More and more, my main passion has become my work with a small press, Endless Editions, that was founded by Paul John and Anthony Tino in 2014 with the aim of supporting emerging and underrepresented artists. In the past two years, I’ve taken the reins as manager, helping to organize the Brooklyn Art Book Fair and arranging programming. It’s all volunteer, though. Any money that comes in goes back to the artists. So now I feel like my job as a tech in the S.V.A.’s RisoLAB and my freelance work are actually in support of my work at Endless. While it’s not helping me survive financially, it gives me other things crucial to my life: I need to be outside multiple times a day, to see people, to make books with other people. It’s given me more space to be a person.

In line with a long tradition in the comics world, you make zines and prints and participate in comic- and art-book fairs. What is the impulse behind self-publishing?

There’s a lot of satisfaction in making my own comics because, when people like it, they’re seeing me, and not me filtered through a bunch of practical concerns, not me appealing to a certain audience. I can just put myself out there and reach people, which creates a very special relationship. That’s what interested me in the first place.

But I was also drawn by the community, because small-press publishing attracts people who believe that art should be accessible. A book is accessible; it’s an object, you can have your own unique relationship to it when you hold it in your hand, versus, say, entering a gallery space, which is inherently élitist—everything there costs ten zillion dollars. There’s also a long political history of zines and community-building that led me to small-press work. I’ve found people that I’m really interested in sharing the same space with, if not through working together, then through supporting one another. And it’s been incredible to participate in that community.

For more Style covers, see below:

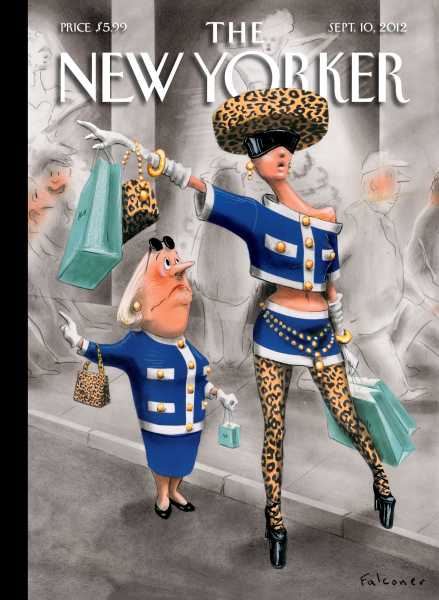

“Stiff Competition,” by Ian Falconer

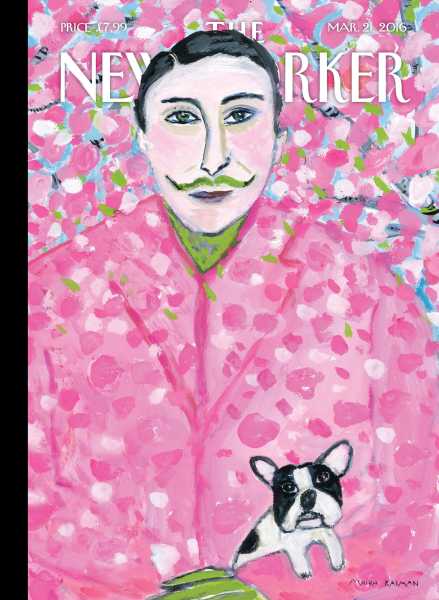

“Spring Forward,” by Maira Kalman

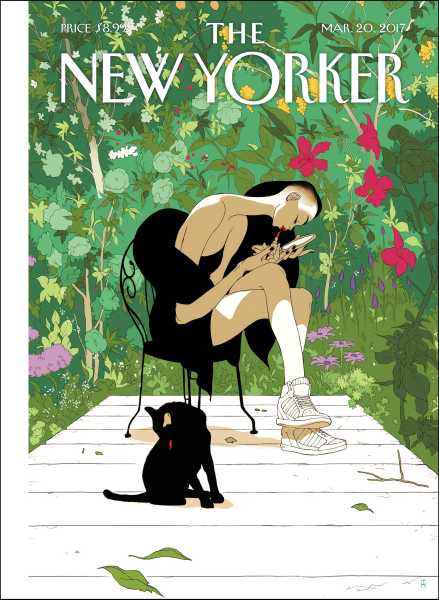

“Spring Awakening,” by Tomer Hanuka

Find Sarula Bao’s covers, cartoons, and more at the Condé Nast Store.

Sourse: newyorker.com