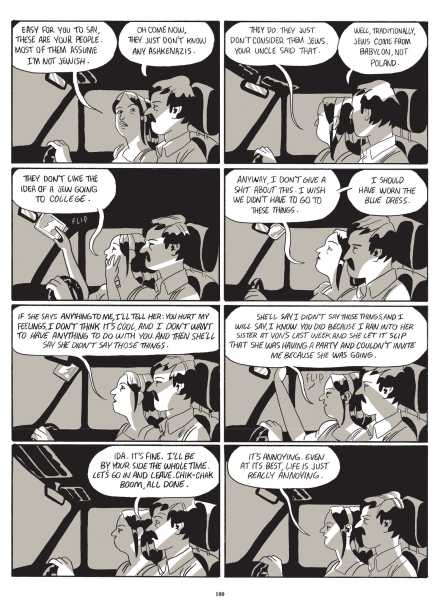

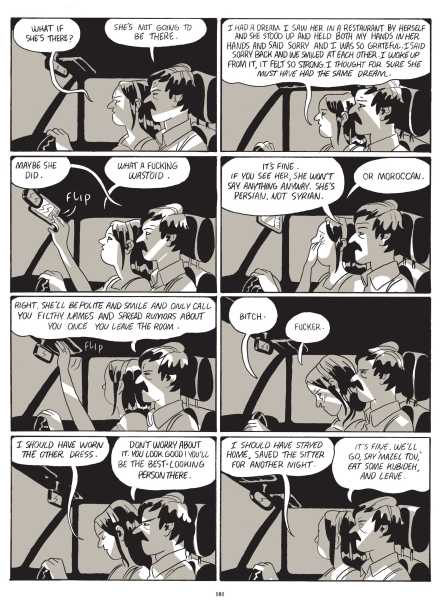

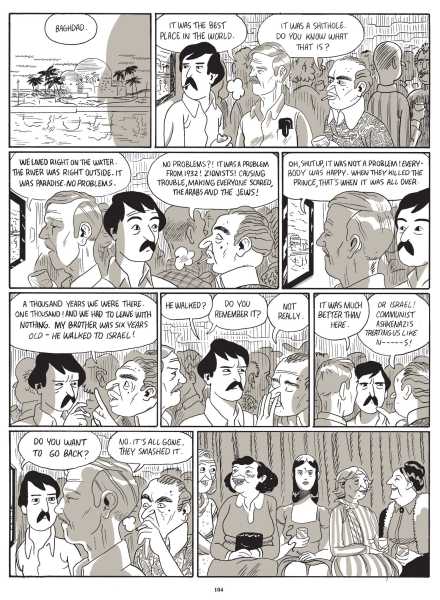

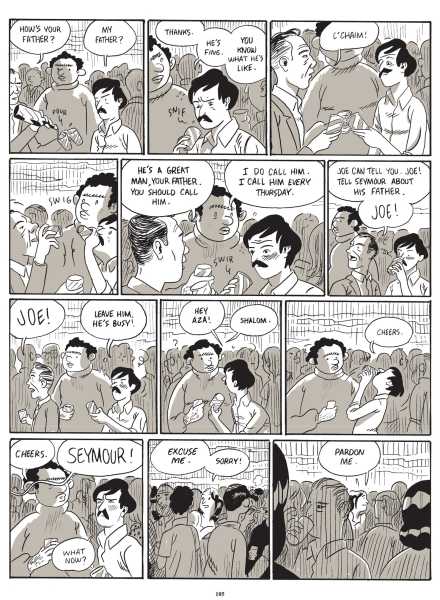

The new book by cartoonist Sammy Harkham, “Blood of the Virgin,” a nearly three-hundred-page magnum opus to be published this spring by Pantheon, is a labor of love. It took fourteen years to complete. Fittingly, it follows its main character, Seymour, through his desire and struggle to realize a creative dream, and details his romantic and familial entanglements in all their messy glory. The twenty-seven-year-old Seymour, who hails from an Iraqi Jewish family, is an aspiring filmmaker in nineteen-seventies Los Angeles. His wife, Ida, was born to Holocaust survivors in New Zealand, and finds herself unmoored as a new mother in their new home. As they settle in California, Seymour’s artistic aspirations jut up against the responsibilities of partnership and parenting, as well as the realities of the film industry. He reckons with losses of all shapes and sizes—the loss of dreams, of generational identity, and of his relationship—and considers the mundane and lasting compromises that life requires.

We talked to Harkham about what inspired him to use comics to depict life in the movie industry of the early seventies.

You spent fourteen years working on this book. Did it turn out the way you planned back when you started? If not, what did you set out to do, and what surprised you about where you landed?

I started the book with amorphous questions and notions, confounding images in my mind that I couldn’t shake; images which, when explored, often became trapdoors to even more confounding images. The creation of the book was a process of digging into a time and a place, and trying to get a grip on it, like looking at an old photo of a family member and straining to understand them. You never get to the bottom of a quest like that. The book continually surprised me during the years I worked on it. I never got sick of it—it was a pleasure, in that way.

To tell your complex story, you use many different styles and graphic approaches. Do you have a system as to what is better shown with each style or as to how you deploy color?

No, I’m not self-consciously formal in that way. I don’t write a script for my comics, so I put a lot of stock in trusting my intuition, into what feels right at any given point in the story. Most of my ideas for scenes are anchored in a strong feeling, in an emotional shape, and every visual decision is in service of capturing that feeling on paper.

You’re also well known as an editor of comics, having produced the anthology “Kramers Ergot” for many years. Did editing a wide range of talented artists serve you as a model for editing your own versatile plethora of styles?

I’m in awe of the artists I got to work with on “Kramers Ergot,” but it would only hinder me to think about them (or any other artist) too much while trying to work. If anything, when sitting at the drawing table, I’m trying to forget every influence, in order to speak as plainly and as honestly as possible with drawing, which serves as a kind of handwriting. You don’t want your voice to echo anyone else’s; you want to speak directly, and that’s not something you can fake.

Most of Seymour’s ambitions are focussed on filmmaking. Do you ever fantasize about being a film director?

No. I love comics and books above all other mediums, and I think one can easily spend one’s life trying to master one good page. Seymour’s love of oft-maligned genre cinema is not that different from loving comics, an oft-maligned medium, so that’s where we overlap. Yet, would a film director ever be asked if they fantasized about being a cartoonist? I doubt it. Theirs is an aspirational and romantic job in our culture, while anyone who chooses to be a cartoonist is looked at as mildly deranged. We don’t pick our poisons.

Many cartoonists—including some you admire, like Dan Clowes—have written and directed films. What do you think a cartoonist, who is essentially a one-man band, can bring to an understanding of the very collaborative medium of cinema?

Very little. Comics, at their best, are the ideal medium to get a deep, unbleached view inside the mind of another person. Marks on paper go beyond language itself. The drawing is the end point of something that starts in the subconscious and works its way out of the brain and down through the arm and out of the tip of a pen. The authorial voice of a cartoonist has a rawness and clarity that is almost unnerving. The work will inevitably reveal more than the artist wants to share. It’s deeply powerful and exciting. Cinema is an entirely different thing in both process and feeling, despite the obvious visual storytelling overlaps, and most cartoonists can’t make the leap between mediums unfazed.

You were born in Los Angeles, and though you moved with your family to Australia at age fourteen, you’re now living back in L.A. with your wife and three children. What is your relationship to the city and why did you want to raise your family there?

L.A. really is a city of ghosts to me. You can feel the energy of all the maniacs who came before you—emanating from the hills and the dusty sidewalks. It’s so, so beautiful. It’s a place that is forever revealing itself in new ways, even for people who have been here their whole lives. So while it’s a frustrating and an ugly place at times, it’s also big enough that everyone can make their own version of the city—tailor it to their own needs and aesthetic pursuits. That’s why you get such a wide variety of wild, wonderful people here, all living very differently from one another. Each can carve out their own little piece and make it work.

Now that you have accomplished such a major œuvre, what are the other projects you’re eager to tackle?

More comics, better comics, God willing.

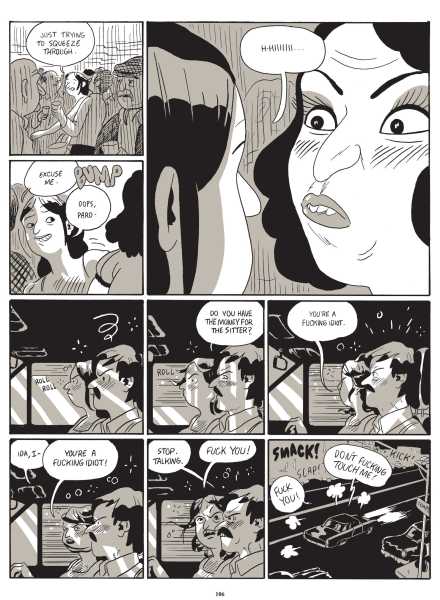

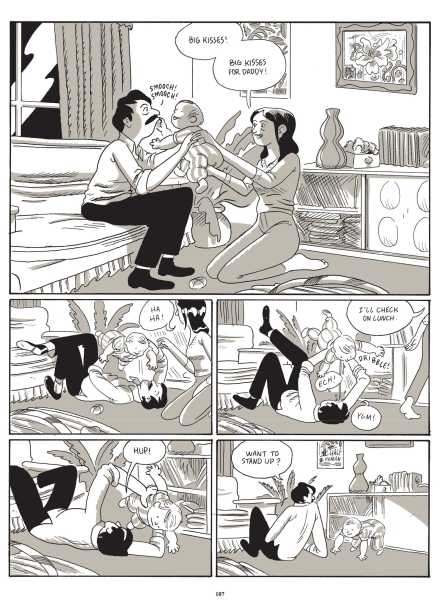

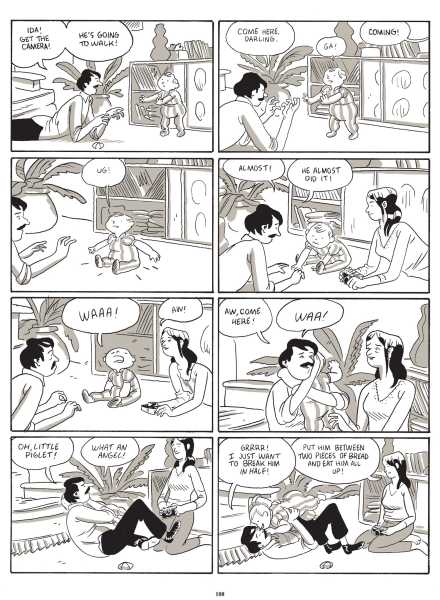

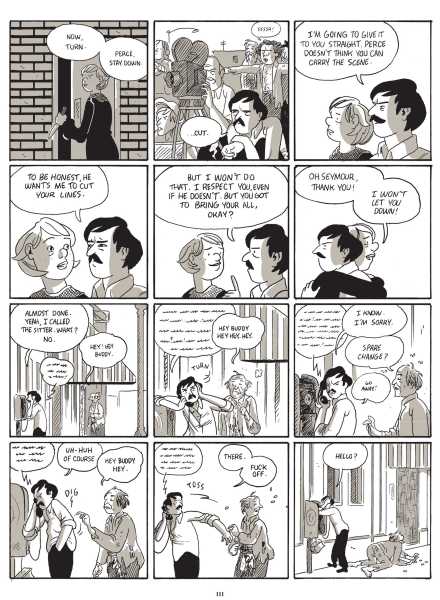

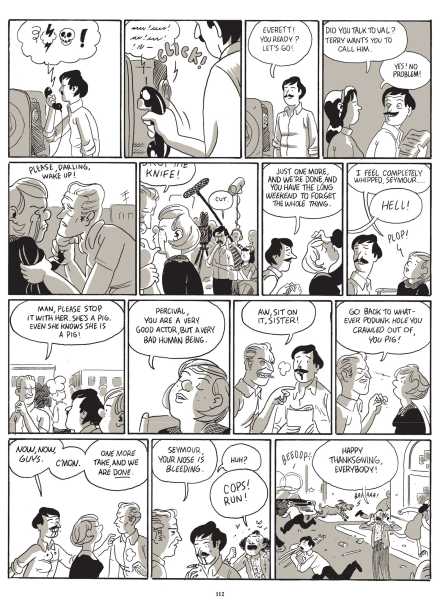

In the excerpt below, Seymour and Ida bicker on their way to a party, and Seymour gets a surprise while directing on the set.

This is drawn from “Blood of the Virgin.”

Sourse: newyorker.com