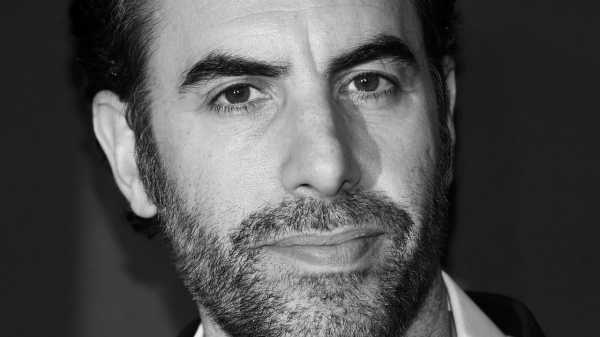

The sporadically excellent conceptual art of “Who Is America?” (Showtime) originates in the impostures of Sacha Baron Cohen and extends to the show’s publicity campaign, which expands the stage of its satire and enriches its terms as both a pop entertainment and a situation prank. The spectacle around the show was born on the Fourth of July, when Baron Cohen posted a video, titled “A Message from Donald J. Trump,” based on old video of Trump wishing violence upon him. Back in the day, Trump was one of Baron Cohen’s unwitting guests on “Da Ali G Show,” where the performer, disguised as one of several foolish characters, would encourage a mark to betray, ideally, a baseness so embarrassing as to call the norms of society into question. Baron Cohen followed his Trump video with a brief tease of the new series in which a relaxed Dick Cheney responds cheerfully to an off-screen request: “Is it possible to sign my waterboard kit?” Soon, news about “Who Is America?” was lodged atop the Drudge Report, like a treasure glittering in a sewer grate, as some idols and élite rogues of the Republican Party—a parade of shady sheriffs, lusty judges, and Fox News fanboys— hastened to get ahead of the news that they’d been had. Their effort gave the spectacle noise and momentum. The hot air blew a fanfare. A distinguished troll of the old school engaged our fresh hell of media manipulation with great aplomb.

In a Facebook post, Sarah Palin accused Baron Cohen of having gained her trust by impersonating a disabled veteran. Palin must have been referring to Billy Wayne Ruddick, Jr., Ph.D., one among a new assortment of usefully idiotic disguises, each with his own funny voice and noisy idiom. Billy Wayne wears a leather coat that suggests a collaboration between Chuck Norris and J. C. Penney, and he rides a mobility scooter decorated with two pins promoting Trump and a newspaper folded to flourish the words “outlet” and “caught” and “Weinstein” in a headline. He publishes a conspiracy-theory Web site called Truthbrary. A bit of text at truthbrary.org, which is done up with persuasively homely graphic design and an apocalypse of misplaced apostrophes, explains the site’s name: “REJECT THE MAINSTREME MEDIA + THE LIEbrary OF FALSE INFOMATION THEY TRY TO PUSH INTO THE PUBLICS MIND’S.” The site now features Billy Wayne’s response to Palin, which includes his all-caps counterdemand for an apology and also a lament that she has lost her way. (“You used to hunt the most dangerous animals in the country, like wolves and people on welfare,” Billy Wayne writes.) Even before the show’s début, it was aerosol-spraying the fourth wall with hostile graffiti.

In the first of this season’s seven episodes, Billy Wayne confronts Bernie Sanders about the horrors of Obamacare: “I was forced to see a doctor, and suddenly I had three diseases.” Also, Billy Wayne proposes to solve income inequality by simply moving one hundred and ninety-nine per cent of the population into the most affluent percentile. A struggle between credulity and courtesy plays out on Sanders’s brow. It is frequently Baron Cohen’s aim to see how far a subject will go in accepting, abetting, and perhaps even surpassing the inanity of a persona. If the figure is guided by skepticism, as in the case of Sanders, the segment transforms into an endurance test of tried patience.

When the subject reveals weakness and vanity, then the way forward is clear for Baron Cohen to agitate and produce savage satire. In the final segment of the first episode of “Who Is America?,” Baron Cohen adopts the guise of a brawny Israeli counterterrorist officer. He’s here today to talk about guns, including the silly suggestion that school shootings are best deterred by arming teachers. “This is crazy,” Colonel Morad says. “They should be arming the children.” The segment collects video of prominent Republicans endorsing the character’s plan to put lethal power in the pudgy hands of “kinder-guardians.”Hats off to the prop department for constructing a “Puppy Pistol”—a hybrid of plush-toy and personal firearm for the “PAW Patrol” set—which looks cuddly-but-deadly enough to support this perfectly calibrated sick joke. The segment is delirious and stunning. How is it possible that Trent Lott, among others, does not see the outlandishness of the teleprompter script he recites? The surrealism of the segment measures the distance between the cruel joke of gun politics and the daily reality of senseless death.

The New Yorker Recommends:

Our staff and contributors share their enthusiasms in books, music, podcasts, movies, TV, and more.

Another new character is like a propaganda caricature of a contemporary progressive—Dr. Nira Cain-N’degeocello, a self-hating white heterosexual cisgender male. (On the eve of the show’s début, a Twitter page associated with the character rested, like an idle bot, at the handle @drmiracain, where it identified him as a lecturer on Gender Studies at Reed College based in Bend, Oregon, and a stay-at-home “Male Mom.”) The good doctor rides his bicycle with a hand-knit pussy hat pinkly stretched atop his helmet and a bushy ponytail flowing at its back. In an oblique reprise of the dinner scene of “Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan,” Baron Cohen, got up in this “Portlandia” drag, ventures to South Carolina to break bread among the silver candelabra of a married pair of Trump supporters. The hosts are ridiculed mostly for their gullibility in accepting their guest’s clowning in earnest. They’re not so much marks as foils. The character, who is ostensibly working to bridge a cultural divide, shares the difficulties of raising children according to his values. He explains that, when his daughter began her menstrual cycles, the family encouraged a program of “free bleeding” on an American flag.

For Baron Cohen, gross-out comedy is sometimes kinetic but always essentially physical. Disgust enhances our vicarious embarrassment. Violations of etiquette prod at taboos. Another new character is a recently released ex-convict with a neck brace, a facial tattoo, and a passion for the visual arts. At a basic art gallery in Laguna Beach, he shares some work he made while imprisoned, with mixed media including excrement and ejaculate, in the tradition of Dash Snow and such. Much of the tension of the segment is in the viewer’s discomfort with settling into it. Is it wrong to bother this random gallerist, who is not exactly Mary Boone? Is the character’s lisp on the wrong side of the line between depicting a speech defect and mocking it? Is the project funny enough to justify its process?

The title sequence of “Who Is America?” opens with a stock scene of pastoral promise, amber waves of grain. It proceeds through a patriotic montage combining footage of Presidential speeches—“Ask not what . . . ,” “Nothing to fear but . . . ”—with film of Jackie Robinson coming home in black and white. And then Trump erupts onto the intro, in footage of the 2016 campaign rally where he curled his right arm and distorted his body to mock the congenital joint contracture of a reporter whom he sought to discredit. Who is America? This cruel buffoon? (And, by the way, does Baron Cohen have any unaired tape of Trump?) The letters and the punctuation of the title flash and dance in red and white and blue, against a black background—a Godard-type design scheme suited to Baron Cohen’s political mission, here, with its “Week-End” vibe of merry derision. “Who Is America?” is a great name for this project, in our new era of craven nonsense. It’s an existential question phrased as an ignorant Google search.

Sourse: newyorker.com