Rosalind Fox Solomon’s vision of the American South pulls whiteness from its position as infinite and invisible “background,” as Zora Neale Hurston once wrote, to instead examine the white body as a site of difference. This by no means translates to capturing only white subjects, as the system haunts any and all who have lived within its nightmarish logic. Like a foreigner—and there was, in fact, a formative period in her youth, in the Midwest, in which Fox Solomon’s Jewish ethnicity made her a person of suspicion—she looks for signs of otherness and strains of the self in the humid embrace of mother and child, the crushed doll, the dilapidated gate of the estate, the cold gaze of couples. These extraordinary portraits and scenes are not quite documentary, but they pursue a truth about fear, pleasure, confusion, family history, and who and what whiteness feeds on in order to cohere.

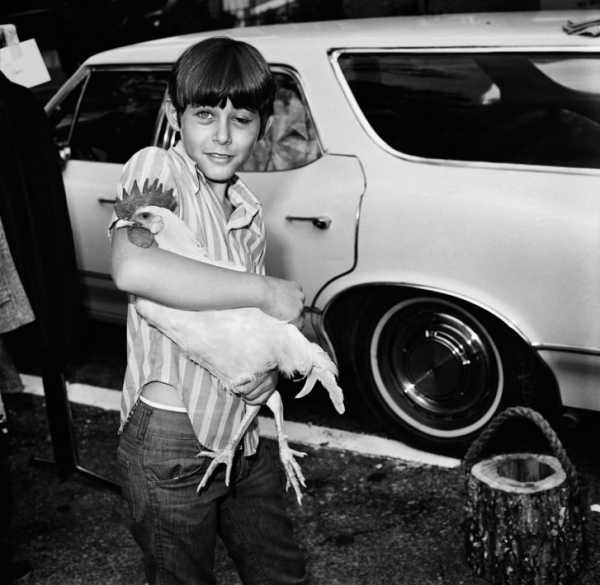

“Boy with Cock,” Scottsboro, Alabama, 1976.

The eighty-eight-year-old master was born Rosalind Fox, in 1930. She was raised in a secular Jewish household in Highland Park, a suburb outside of Chicago, by an aloof father and a dissatisfied mother. The childhood was one of “white gloves, white teeth,” she has said, and a degree of loathing, courtesy of her mother, who “hated the fact that she was Jewish,” even though “all of her friends were Jewish.” Perhaps owing to hostility from home and from schoolmates—she has recalled “dirty Jew” being hurled at her on her walks home—Fox Solomon internalized, from a young age, that forging an identity requires witnessing how the perceptions of others invade you. She has described her photography, which turns outward in order to look in, as a method of “talking to myself.”

“Cotton Hearts,” Scottsboro, Alabama, 1974.

“On the Road and Going Somewhere,” Mississippi, 1997.

Before Fox Solomon travelled to the Far East and to the Global South to take pictures of “chaos and pressure” during wartime, before she was ostracized by a dishonest and politicized viewership for her honest series “Portraits in the Time of AIDS,” and well before she became a student of the Austrian artist Lisette Model and her revolutionary bluntness, Fox Solomon got married. And, in 1953, she moved to Chattanooga, Tennessee, to join her husband’s tribe, where she absorbed shocks. The Solomons owned movie theatres, including a blacks-only one. The connection to segregation filled her with guilt. When the Civil Rights Act passed, in 1964, Fox Solomon rejoiced, alongside the new black friends she had made. But the Gothic trouble in the theatre’s name—freedom as an illusory set of images that both blacks and whites have a reason to be tormented by—stayed with her.

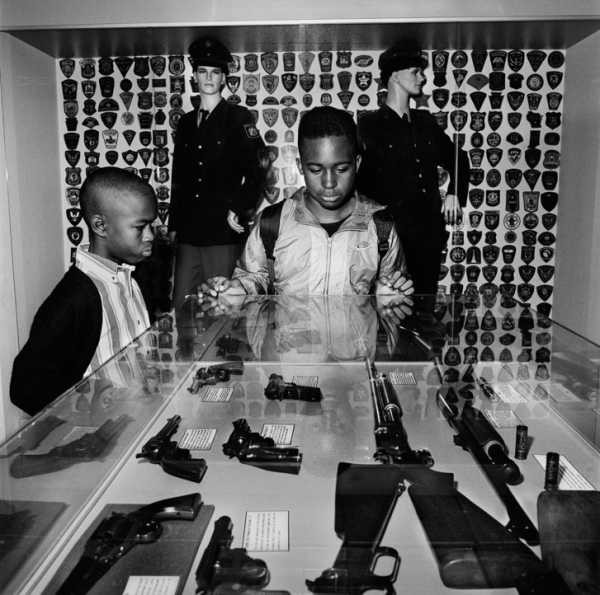

“Police Museum Tour,” Miami, Florida, 1994.

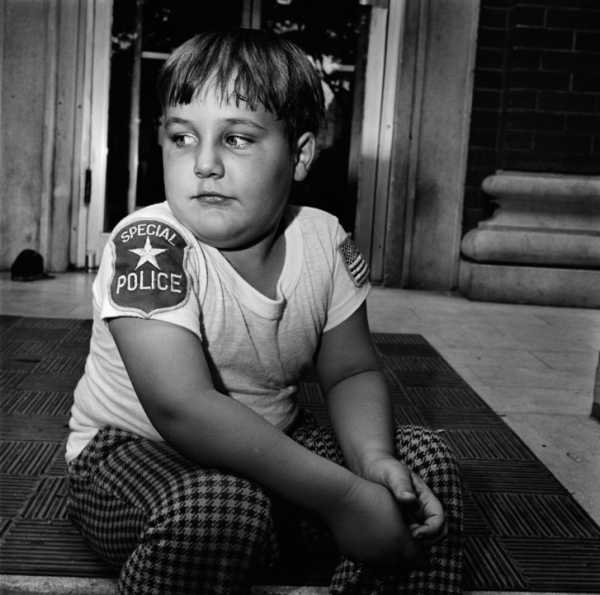

“Little Policeman,” Scottsboro, Alabama, 1975.

And, with “Liberty Theater,” her fifth monograph, the artist revisits her uncanny excoriation of the great myths of the South. Taken in the early-to-middle stage of her career, the images span from the seventies to the late nineties, and document the children and the enforcers and the workers of seven states. Like the photography of Diane Arbus, who also studied with Model, all of her work is black and white. But their color vacuum only increases our hunger to have seen for ourselves these spaces of lust and racial lunacy, mask and metaphor, family connection and interpersonal breakdown. No work can truly be post-segregation, because the color line, as W. E. B. Du Bois prophesied, remains viciously entrenched on psychological and physical ground. So “Liberty Theater” captures the color line’s psychic work, its oppressive potential to frame and dictate how we see.

“Foxes Masquerade,” New Orleans, Louisiana, 1992.

New Orleans, Louisiana, 1993.

The first image in the book, a menacing still-life of Americana including a K.K.K. belt buckle and beer medallions, is not representative of what we will experience on subsequent pages but, rather, a catharsis, asking us to cleanse our eyes of stock representation and documentary cliché. The book will allow us a forbidden travel. Next are successive portraits of manageable pathos, of two different white women who could be one: the first, older and gleaming, under a cotton bonnet, and the next, younger and nervous, mouth-dropped, turned sidewise so that we see one drooping hair roller. After that comes a gate and a plantation-like home in the distance, which gets us thinking about the ghost economy of slavery, the institution that may have separated the races but also placed them in ruthless and unending reciprocal relation. And then, like an angel of innocence, there is a black girl with barrettes, squinting a bit under a Mississippi sun. Do the earlier women think about her, and has the legacy of their agency already limited how she thinks of her own?

“Sick Child,” Chattanooga, Tennessee, 1975.

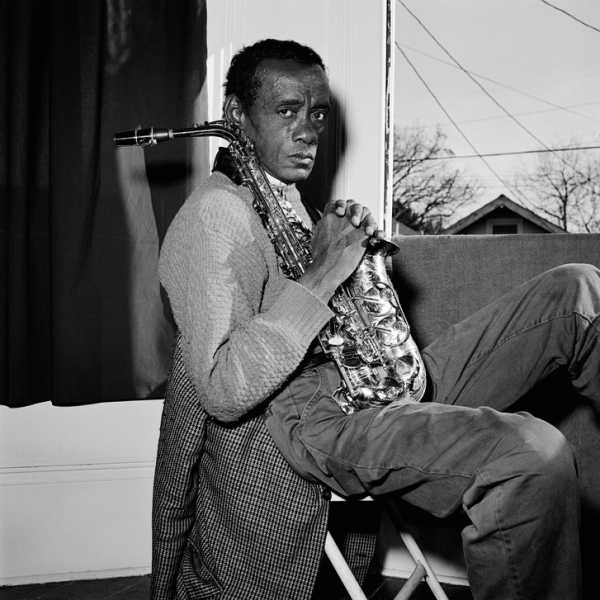

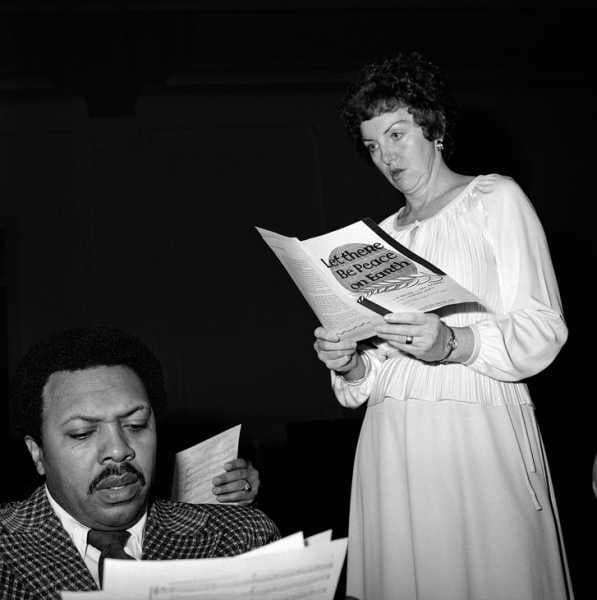

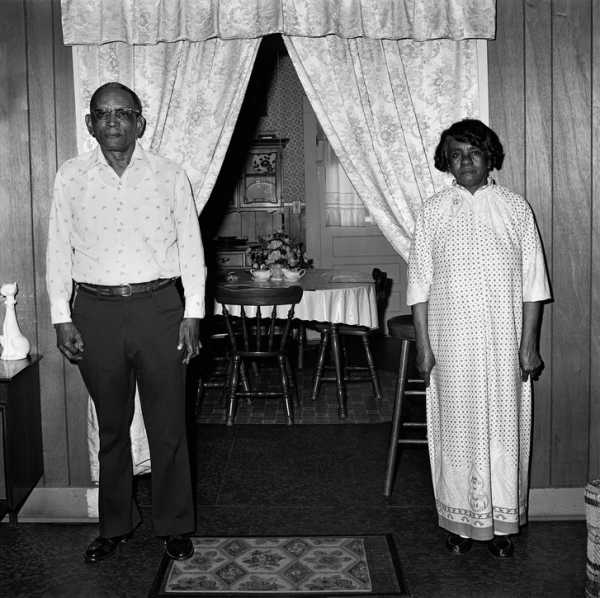

Fox Solomon has said that she barely talks to her subjects during the process of photographing them: “Rather than make people feel at ease, I find that some tension between me and the person I am photographing yields something more complex.” “Liberty Theater” taught me something about the power of viewer discomfort, which has been depressingly eroded in our era of artistic pandering. Looking at the stiffened old black couple standing on opposite ends of their doorway, emanating all the vitality of a Victorian corpse portrait, I wonder what alchemical effect Fox Solomon has on her black subjects in their black spaces. It’s one that seems to be built not on trust but on more candid, and more revealing, forces: secrecy and distance. The saxophonist clutches his instrument and glares, judgy, wary. Fox Solomon’s scenes telegraph the well-earned feelings of prejudice that blacks had toward photography and its threatening ability to reduce them to totems.

“Singers,” Washington D.C., 1979.

“After the Funeral,” New Orleans, Lousiana, 1992.

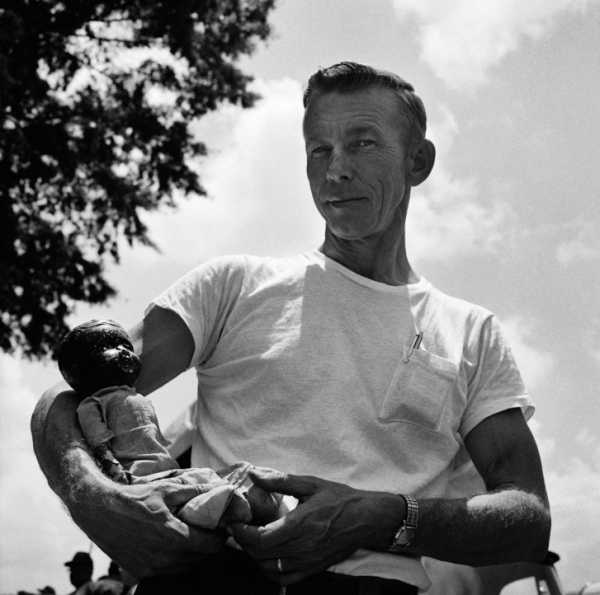

But how did her whiteness and her class work on white people? Here, some of the photographs are chilling. A favorite, and a difficult one, is “Battered Doll.” Fox Solomon will frequently shoot men from below their center of gravity, which renders them portentous stereotypes of the sky. This figure, mildly grinning, has a tight haircut and tight T-shirt, which exude militarism, and a paternal pose, which rouses hope. But the “baby,” the promise, he’s cradling is a maimed black baby doll. The hacking could have been the work of a child—his child? his black child?—or perhaps a prop of Fox Solomon’s, who first learned about eeriness through photographing dolls. Its comment on the link between care and destruction is strong, but what is overwhelming is the man’s look, which says, I know what you’re thinking and I’ll never tell. The inscrutability of white power is one of Fox Solomon’s recurring themes.

Leland, Mississippi, 1977.

Dark humor runs through “Liberty Theater,” a collection that is in profound touch with the Southern thirst for domestic pageantry. Fox Solomon gives the drama of racism its garishness. How else does one cope with the tragicomedy of “Boss, Peanuts, Sorter, ” where a murderous misery wrinkles the black female worker’s face, while her white boss stands by in buffoonish bliss? Or the poem of the older white woman at church, ignoring the lyrics on her “Let There Be Peace on Earth” pamphlet, so she can glare at the black man in the congregation beneath her? Violence, a kind of intimacy, is always a possibility, and then so is sex. Fox Solomon’s distinctly humanistic understanding of the paradoxes of the South, where the secessionist flag waves but blacks and whites are more integrated socially than in the North, composes many portraits of the sexual politics of interracial union. Some are hopeful, some are ugly, some are wild, and some seem hermetic, sealed off from the deadening hierarchies of the world.

“Ready to Fire,” Scottsboro, Alabama, 1976.

There is no artist text to orient us in “Liberty Theater.” (“Seeing comes before words,” as John Berger wrote.) The geographical captions of “Mississippi,” “Alabama,” and “Tennessee” are enough to set the mind remembering. There are discomfiting images from pro-gun rallies and of the paranoid effects of the Scottsboro Boys trials, as in a scene of a white woman in Scottsboro, standing sentinel with a gun, around the time George Wallace pardoned the last of the wrongly accused. But the genius of her work is that it does not tend to present its violent histories straight. Cruelty lurks, looks calm, hardens into an action, or dissipates into nothing. We do and don’t know. There is one exception in “Liberty Theater.” It is a closeup of a beaten black man, unceremoniously slotted between a primadonna getting highlights and a working couple taking a lunch break at a Burger King. His face horrendously recalls that of the earlier battered doll. The lack of an explanation is maddening. Who did this? Who is he, and did he survive? Can anyone?

Chattanooga, Tennessee, 1975.

“Battered Doll,” Scottsboro, Alabama, 1975.

Sourse: newyorker.com