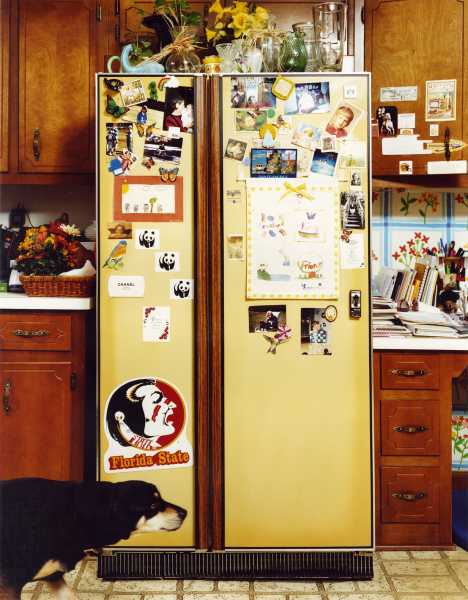

The first picture in Roe Ethridge’s “American Polychronic,” his hefty new slab of a career survey from MACK, is of a butter-yellow, two-door refrigerator covered with papers and snapshots, in his parents’ suburban Atlanta home. As an introductory image, it’s at once spectacularly insignificant and, in the style of William Eggleston, casually iconic, even a little marvellous. It’s a style that, since the turn of the new millennium, Ethridge has redefined on his own terms, and with remarkable success in both art and commerce. Like so many contemporary photographers (Wolfgang Tillmans, Collier Schorr, Juergen Teller, Cindy Sherman), he doesn’t isolate his editorial from his gallery work, and in “American Polychronic” they are thoroughly shuffled together. Trying to distinguish one from the other is both futile and pointless. As two aspects of one career, they inform, spark, and subvert each other—which brings us back to that refrigerator. Ethridge shot it as part of an assignment for the New York Times Magazine that was never published, but he liked it too much to let it die. He included it in a show at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, in the summer of 1999, where it was seen as a signature image. A year or two later, it appeared in a print ad for a kitchen-related product that never took off. Now, Ethridge says, he sees it as “a bit of a key to everything.”

“Refrigerator,” 1999.

“Gossip Girls for Dazed,” 2021.

“American Polychronic” is full of photographs that slip among definitions and functions, refusing to be pinned down. If Ethridge wasn’t so good at this, he could be dismissed as a joker, a provocateur. He already flirts with the role. The second picture in his book is a self-portrait, in which he looks handsome, scruffy, and vaguely preppy, but with a gorgeous black eye. As a portrait of the artist as a young punk it’s hard to beat, except that Ethridge topped it with a shocking head shot of the performance artist and rocker Andrew W. K. with blood streaming from a busted nose. It’s an exaggeration to say that those two portraits made Ethridge’s career, but they immediately made him someone to watch.

“Self-Portrait,” 1999.

“Andrew W.K.,” 1999.

He was also someone difficult to keep up with. “American Polychronic” features more than four hundred and fifty pages of pictures made between 1999 and 2022, including many that audiences haven’t seen before, either on a gallery wall or an editorial page. Aside from a slew of magazine covers (Vice, Self Service, Texte zur Kunst, Aperture), much of the work appears deliberately context-free. The result is an overload of images, both indigestible and irresistible. A note at the end of the book explains the sequencing, which is chronological but with a twist—the art-exhibition work is ordered oldest to newest, the commercial work newest to oldest, and there are “too many exceptions to this rule to mention.” To make things even more disorienting, the only captions are included on a few scattered pages as screenshots of text files, which, the photographer points out, are “images,” too.

“Spaghetti Junction, Atlanta, Georgia,” 2003.

“Great Neck Mall Sign,” 2006.

“Moldy Peach,” 2020.

Ethridge has always played fast and loose with the idea of the picture as document. Some of his best photographs record just what the camera sees: a bowl of moldy fruit, an overflowing ashtray, strip-mall signage, a black-gloved hand holding a ripe red apple. Many more of them are manipulated, both obviously and subtly, with results that range from arresting to cheesy. Ethridge’s fashion work tends to be faux generic: spoofs of catalogue shoots, they are amusing one by one but grating en masse. But more often than not Ethridge knows how to make the balance between attraction and repulsion tip in his favor.

“Louise Parker for Luncheon,” 2016.

“Lightning,” 2003.

“Decanter with Fish for Tiffany,” 2017.

In a conversation with the critic and curator Antwaun Sargent at the end of the book, Ethridge explains that in high school he was excited by the work of Warhol, Lee Friedlander, and Irving Penn. But he says that stock photography “felt like the script I was supposed to pick up,” adding, “This sort of generic, Methodist, Southern, middle-class world was mine.” After graduating from the Atlanta College of Art, he assisted catalogue photographers and began to think, What if I worked as a commercial photographer and made the images that Richard Prince is appropriating? As an ambition, that was at once modest and perfectly pitched. His discovery of the great oddball Paul Outerbridge, who made disconcertingly conventional commercial work alongside fetishized nudes and high-modernist still-lifes, was encouraging. Ethridge sums him up simply: “He was an American who wanted to be an artist but needed to make some money.” With Prince and Outerbridge as guideposts, he charted his own eccentric route between the gallery and the marketplace. Ethridge may not end up in the comfort zone, but he has plenty of room to play.

“Lakeith Stanfield for CR Men’s Book,” 2018.

Sourse: newyorker.com