Waiting to be let into the gallery to see the Metropolitan Museum’s “Richard Avedon: MURALS” exhibition, a friend leaned over and asked me, “Haven’t we seen this before?” Well, yes and no. Gagosian showed four of Richard Avedon’s large-scale, multi-panel group portraits—“Allen Ginsberg’s Family,” “The Chicago Seven,” “The Mission Council,” and “Andy Warhol and members of The Factory”—at the gallery’s massive space on Twenty-first Street, in Chelsea, in the spring of 2012. The installation, designed by the Ghanaian British architect David Adjaye, drew almost as much comment as the works themselves. Standing in the middle of the gallery, surrounded by high white walls, viewers could glimpse each of the murals in the distance, down corridors that opened up into enclosures hung with smaller photographs. The clash of maximalism and Minimalism was overwhelming and not entirely flattering to the images. Avedon’s biggest photographs, rendered in the scale of history paintings (or Times Square billboards), seemed oddly downsized, their impact diffused in all that imposing space.

“The Mission Council, Saigon, South Vietnam, April 28, 1971.”Photograph courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, © The Richard Avedon Foundation

That’s hardly a problem at the Met, where three of those four murals (all except “Allen Ginsberg’s Family” were Avedon donations to the Met in 2002) are installed in a long and relatively narrow gallery usually dedicated to photography on a more conventional scale. Here, it’s the work that overwhelms, as it was intended to. Each piece is ten feet high; the largest is thirty-five feet long. At Gagosian, they were hung behind plexiglass barriers. At the Met, they are naked, protected only by low barriers designed to keep viewers at a safe distance but allowing for a startling and tantalizing intimacy. Even before you take in the subjects of Avedon’s work, you can’t help but appreciate its terrific physical presence. Otherwise traditional gelatin-silver prints on heavyweight photographic paper, the murals are backed with linen and they hang like tapestries, with no apparent supporting hardware and a distinct curl at the base. The installation doesn’t allow for much big-picture contemplation—if you pull very far back from one image, you’re backing right into another—but the trade-off in close examination is worth it.

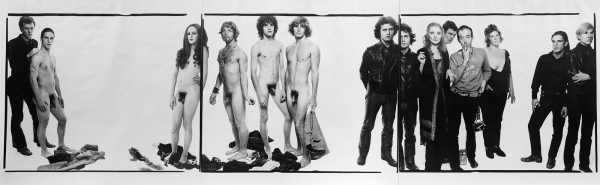

“Andy Warhol and members of The Factory, New York, October 30, 1969.”Photograph courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, © The Richard Avedon Foundation

At the time the murals were made and first shown, in the late sixties and early seventies, their size was more remarked upon than their contents. This was long before Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff, and Jeff Wall. No other photographers were working at such a large scale. But Avedon was coming off a period when he felt that his portrait work had come to a standstill, and he was determined to make a breakthrough. Outrageous scale was crucial, even if that riled some viewers, who found the murals not just wildly ambitious but show-offy. If Avedon was stung by the criticism, he wasn’t cowed. He’d found a way to adapt the directorial mode he’d refined over the years in his fashion work to create group portraits that were charged, complicated, impeccably finished, and impossible to ignore.

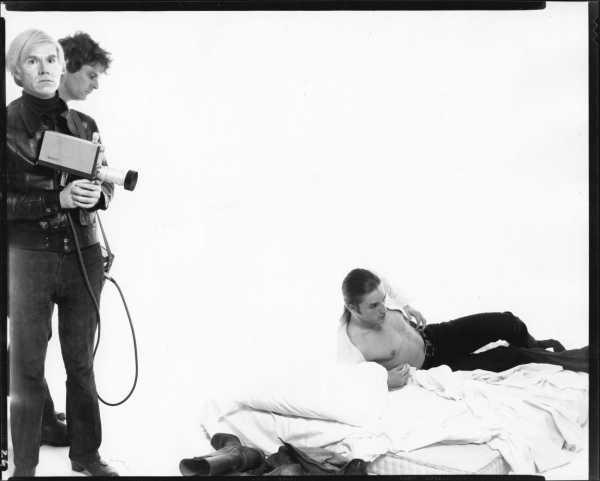

“Outtake from Andy Warhol and members of The Factory, May 21, 1970.”Photograph courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, © The Richard Avedon Foundation

“Outtake from Andy Warhol and members of The Factory, October 25, 1969.”Photograph courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, © The Richard Avedon Foundation

The most successful, most memorable, and the most difficult piece to pull off was “Andy Warhol and members of The Factory.” It is dated October 30, 1969, but was begun months earlier, on August 14th, in a session that served as both a test run for Avedon and a tryout for his subjects. Over the following months, he refined his cast of characters and orchestrated their relationships across the bright, featureless white space that had become his signature. Warhol was always present at one end of the frieze, holding his tape recorder at the ready. Eventually, Avedon decided to introduce a bit of drama to the scene, anticipating the jealous antagonism that the filmmaker Paul Morrissey was beginning to exhibit toward Warhol, over the shifting alliances of his protégé Joe Dallesandro. In the final image, a composite, Dallesandro appears naked and under Morrissey’s possessive hand, at the left edge of the mural, and also clothed and close at Warhol’s side, on the right. In between, Morrissey reappears—behind a group that includes Viva, Taylor Mead, and a breast-baring Brigid Polk—and casts a suspicious eye on his rival. That friction gave Avedon the same hint of narrative that had driven many of his most successful fashion photographs, but the Warhol mural hardly depends on it. Not when the actors Jay Johnson, Eric Emerson, and Tom Hompertz make an unlikely version of “The Three Graces,” casually nude amid a tangle of their cast-off clothes. And especially not when the uncommonly beautiful Candy Darling stands just as naked nearby, in wig and full makeup, with what she referred to as her “flaw,” a penis, on matter-of-fact display. Although none of this looks especially groundbreaking today, it was rather extraordinary at the time, and it still reads as a marvellous coup, at once shrewd and playful—far from spontaneous yet full of surprise.

“Outtake from Andy Warhol and members of The Factory, October 9, 1969.”Photograph courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, © The Richard Avedon Foundation

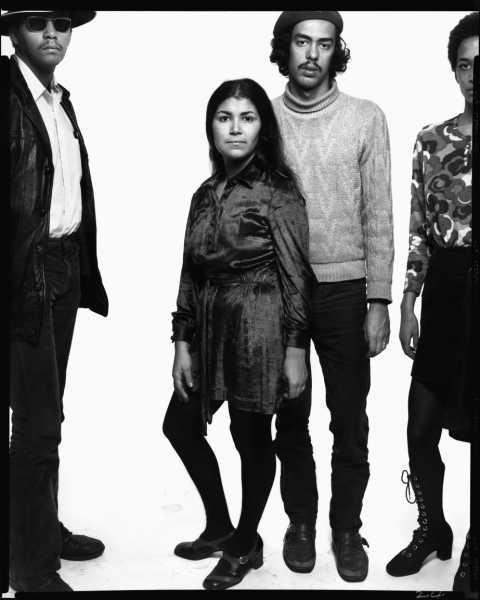

Avedon’s interest in the counterculture and the radical left was never idle curiosity. The Warhol sessions and the other murals and related materials at the Met were produced as offshoots of a project titled “Hard Times,” which occupied him and his collaborator Doon Arbus (Diane’s elder daughter) for much of the sixties and early seventies. The exhibit includes smaller images made in Vietnam, where Avedon photographed journalists, shoeshine boys, napalm victims, and the members of the Mission Council, and in New York, where he set up sessions with the civil-rights lawyers William Kunstler and Florynce Kennedy, the Weather Underground leader Bernardine Dohrn, and members of the Puerto Rican activist group the Young Lords.

“The Young Lords: Pablo ‘Yoruba’ Guzmán, Minister of Information; Gloria González, Field Marshal; Juan Gonzaléz, Minister of Education; Denise Oliver, Minister of Economic Development, New York, February 26, 1971.”Photograph courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, © The Richard Avedon Foundation

“Hard Times” grew sprawling and unwieldy, and Avedon eventually abandoned it, but the work was critical to his creative advances in that period. (Much of the material, including Arbus’s interviews and texts, was published in a 1999 book titled “The Sixties.”) His group portraits “The Mission Council” and “The Chicago Seven” became the templates for his 1976 Bicentennial Rolling Stone project, “The Family,” which comprised sixty-nine frontal, deadpan studies of the American establishment, from Ronald Reagan to Katharine Graham. The Met exhibition celebrates another milestone: a hundred years since Avedon’s birth. From early on, he was anxious about his legacy, and no accomplishment or breakthrough could put that anxiety to rest. Nearly twenty years after his death, one can’t help imagining his brow furrowing over every damn detail of the Met’s installation. He needn’t worry. The work is as tough, intelligent, and vivid as he was.

Sourse: newyorker.com