The French miniseries “Represent,” which is streaming on Netflix, veers toward movie-ness for practical reasons. With its six half-hour episodes, it’s shorter than many features, and all six are directed by the same person, Jean-Pascal Zadi—who is also its star, its co-creator (with François Uzan), and the co-writer of every episode (with Uzan and others). Zadi is a longtime director of independent films and music videos, and is also a rapper and a comedian. His 2020 feature, “Simply Black,” a comedy about the efforts of a well-intentioned but blundering Black French actor (played by Zadi) to convert his artistic frustration into political action, is among the most effervescent and pointedly original of recent French films. Like that film, “Represent” is something of a one-man show, albeit one that teems with a broad array of characters and settings, and that embraces a wide-ranging vision of France at large.

“Represent” essentially starts where “Simply Black” left off: the feature film, set in Paris, is centered on the lack of Black people, and of meaningful depictions of Black lives, in French media. “Represent,” however, is anchored in the workaday lives of Black people who are shunted off to massive, ghetto-like housing projects in the suburbs of Paris. The series is premised on their lack of real political power, owing in part to the false and distorted images of Black people that the media perpetuates—and the show dramatizes, with a grandly conceptual exaggeration, a comedic fast lane to that power. Zadi plays Stéphane Blé, a youth counsellor in a housing project, who is transformed by a rapid turn of circumstance into a candidate for France’s Presidency. The series is filled with extravagant (and sometimes far-fetched) byways, sharp satirical observations, and comedic performances that range from antic to caustic, from self-deprecating to moralizing. Unlike “Simply Black,” “Represent” groans under the weight of convention, or of dictate, but its ideas are as potent as those of the movie, and are even more diagnostically significant. “Represent” draws its over-all force from a surprising and audacious idea: an attempt to define, and to redefine, France’s political left.

The front-runner in the Presidential campaign, Éric Andréï (Benoît Poelvoorde), is a doughy, middle-aged, white left-wing candidate who is tacking toward the center; he’s also the mayor of the suburb in which Stéphane lives. When Éric arrives for a photo op at Stéphane’s housing project, campaign handlers and media in tow, Stéphane, a longtime acquaintance, bluntly and wittily challenges him on his policies and his attitudes regarding the project’s residents. The video of the takedown goes viral, it gets broadcast on TV, and Stéphane becomes an instant celebrity. When some news commentators facetiously imagine him as a candidate, an experienced political consultant, William Crozon (Éric Judor), who’s also Black, takes the idea seriously and recruits Stéphane to run.

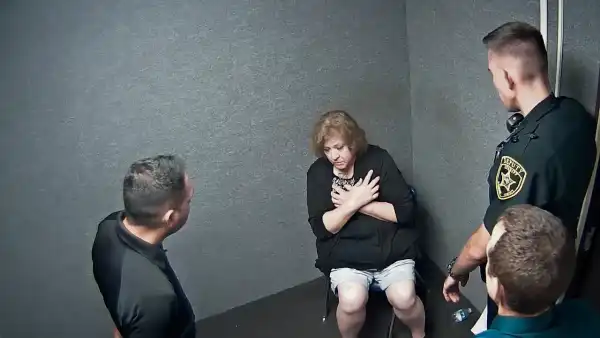

The series cast a satirical spotlight on a wide range of French political and social ills, primarily ones involving France’s deep-rooted and largely unchallenged racism, which targets nonwhites of any ethnicity. One far-right candidate campaigns on a platform of expelling “Arabs” (i.e., North Africans and Middle Easterners) from France. After Stéphane declares his candidacy, white people in a focus group associate him with “the projects,” drug dealing, and polygamy. The police are presented as hostile occupiers who arouse fear and sow chaos. (When Stéphane questions police about the dubious arrest of a young man, he, too, is arrested, and the police assail peaceful protesters with pepper spray.) As for Éric, an ostensible Socialist, Stéphane challenges him for shifting funds from social services to security measures and for pursuing educational programs to prepare children of the projects for manual labor only.

When Stéphane undertakes his candidacy, he’s not running to win but to get out his message about the deprivation, frustration, oppression, and exclusion of French people of color. He’s playing politics for the media attention, whereas William has dubious motives of his own for launching Stéphane into a real and serious candidacy, which, fuelled by Stéphane’s candor and charm, takes off. The men are aided by Yasmine (Souad Arsane), a graduate of a prestigious school of government, whose administrative skills and media savvy give stability and credibility to a freestyle campaign. Yet Zadi delights, with bitter humor, in the chicanery, double-dealing, and backstabbing that take place behind the scenes of political life. The underlying rumble of “Represent” is: who benefits? It’s obvious from the start that the rise of an outsider leftist like Stéphane is a boon to the far right, and that, as the butt of Stéphane’s nationally celebrated display of wit, Éric is more threatened by his candidacy than are Stéphane’s ostensible political adversaries—and, consequently, Éric plays even more dastardly games to undermine it.

Amid the high-level machinations taking place behind Stéphane’s back, Zadi presents exactly the kind of street-level stories that the candidate himself is trying to put on the national stage. Stéphane is married to Marion (Fadily Camara), who owns a beauty salon and is struggling to pay back her loan on the shop. The couple is trying to have a baby and needs to rely on in-vitro fertilization to do so. (The scheduling of medical appointments—complete with Stéphane’s on-site delivery of sperm—around his political obligations is an inevitable element of comedy.) They share an apartment with Stéphane’s mother, Simone (Salimata Kamate), who’s from Ivory Coast; a devout Christian, she and her friends express deep-rooted, albeit trivial, prejudices against people of Senegalese and Malian descent (including Marion). They sprinkle conversations casually with prayers and sometimes sprinkle people with holy water. What emerges is warmhearted, sitcom-like family joshing and antics that reflect an essential average-French normalcy, one that gets nonetheless knocked out of whack by all that’s uneasily abnormal in the situation of Black people living in the projects. The foreclosed opportunities prompt an enterprising young man named Désiré (Homayoun Fiamor), Stéphane’s cousin, to become a local marijuana lord, and then to get entangled in political intrigues that cause trouble in Stéphane’s campaign and marriage alike.

Stéphane, too, is also the target of some stinging satire—some of it dubious and tone-deaf, as when he admits to having drunkenly pressured a woman into sex, years earlier, in an incident that Yasmine investigates as rape but that is revealed, with a sordidly dismissive humor, as having been altogether innocuous. The comedy hits more cleanly in the repeated trope of Stéphane stumbling into microaggressive faux pas toward Yasmine, who wears a hijab; at the start of a campaign trip to a remote, seemingly all-white rural village, where he asks her to remove her hijab, she retorts, “Yeah, sure, no problem, as soon as you stop being Black.” That trip, the series’ most elaborate and extended sequence, gives rise to Zadi’s most purely comedic inspiration, when a churchgoing white couple obliviously coaxes Stéphane to sing gospel for them, and he delivers a giddily fractured rendition of “Oh Happy Day”—a song that he doesn’t know.

The series features violence on the part of a white racist (albeit with a comedic upshot), spurious police raids, large-scale hacking of candidates’ e-mails, and plenty of ribald humor. But, for all the exuberance of its fine-grained yet high-energy cast, and despite Zadi’s blithely mighty performance at its center, “Represent” doesn’t match up to the artistic originality of “Simply Black.” In the feature film, the scenes tend to run at length, giving Zadi and his fellow-actors time to riff while also providing the star with enough space to maneuver—and its mockumentary basis, featuring Zadi in a role bearing his own name, allows him to conjure a sly, daring complicity with viewers. By contrast, “Represent” is an unambiguous fiction that runs tightly, with generally brief shots, impatient editing, and dialogue and action cut to the bone of informational necessity—yet it nonetheless energetically delivers Zadi’s bold and bracing political message.

Avoiding spoilers, suffice it to say that Stéphane’s most formidable rival is another leftist, Corinne Douanier (Marina Foïs), the environmentalist candidate, who’s running on a “green” platform of degrowth and makes opposition to nuclear energy a touchstone of her campaign. She’s less a target of Zadi’s satire than the other candidates (only her dumpster diving comes in for a glance askance), because her unimpeachable principles and probity set up not a clash of personalities but a serious conflict of ideas (which is nonetheless couched in broad comedy). The series suggests the cruel absurdity of advocating degrowth to citizens who’ve been deprived of the benefits of the country’s years of growth. Though the tone stays bright during scenes in which Corinne and Stéphane face off, Zadi makes Stéphane his mouthpiece to define racial, ethnic, and religious equality as the core ideal of the left, as the fundamental basis of economic justice and social progress. The series leaps out of its frame and into the real political arena with the suggestion that it takes an outsider, an amateur, such as Stéphane to say so—that racial justice has little place in France’s actual political establishment. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com