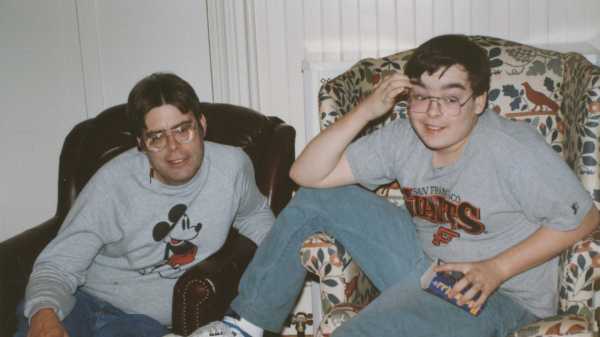

My father gave me my first job, reading audiobooks on cassette tape. He had caught on to the medium early, but, as he explained later, “There were lots of choices as long as you only wanted to hear ‘The Thorn Birds.’ ” So, one day, in 1987, he presented me with a handheld cassette recorder, a block of blank tapes, and a hardcover copy of “Watchers,” by Dean Koontz, offering nine dollars per finished sixty-minute tape of narration.

This was an optimistic plan on my father’s part. Not only was I just ten years old, but when it came to reading aloud I had an infamous track record. My parents and I still read books together each night, and I had recently begun demanding an equal turn as narrator. Along our tour through Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Kidnapped,” I had tested their love with reckless attempts at a Scottish accent for the revolutionary Alan Breck Stewart, whom the novel’s protagonist, David Balfour, befriends. Even as they pleaded for me to stop, I made knee-deep haggis of passages like the following:

“Do ye see my sword? It has slashed the heads off mair whigamores than

you have toes upon your feet. Call up your vermin to your back, sir,

and fall on! The sooner the clash begins, the sooner ye’ll taste this

steel throughout your vitals.”

Despite this, my father enlisted me to narrate “Watchers.” (If Stephen King wants to listen to a Dean Koontz novel, he will listen to a Dean Koontz novel.) And for those nine dollars—an outrageous wage—I did, in fact, complete the task. Or I read “Watchers” as well as any ten-year-old could, seated at my bedroom desk beneath a poster of Roger Clemens in mid-delivery, stuttering my way through the hard words and letting the tape fill with room tone while I paused to contemplate the longer sentences.

The plot of “Watchers” follows a super-intelligent dog that communicates with his human master, an ex-Delta Force commando, via Scrabble tiles. Wikipedia tells me that the main threat in the story is a genetically altered baboon, which does sound frightening, but the Scrabble part is what I recall. One of the shortcuts that bad critics use to signal their dislike of a genre novel is to list all the wild elements—i.e., “ ‘[Novel Title]’ features a battleship in 1943, Siamese twins in 2017, a subplot involving a serial killer named Ducky, and a corpse that vomits locusts”—without putting them into any sort of context. I suspect that part of the reason that Dad still loves to kid me about “Watchers” is that he’s justifiably sensitive to this kind of dismissal. For the record, I would never reject out of hand a novel about a magic dog, an ex-Delta Force commando, and a genetically altered baboon. I’m certain that I didn’t actually say I hated the book. It just bothered me, the convenience of this singular dog being found by an ex-Delta Force commando. That was awfully lucky, wasn’t it?

I’d read plenty of books, but I hadn’t thought much about them; I’d just consumed them. Paperbacks from the “Three Investigators” series lay in drifts around my bed, enjoyed and discarded. But, when I closed my bedroom door, sat down, pressed the red button on the tape machine, and began to narrate aloud from “Watchers,” my experience of reading shifted. As always, the story made the world fall away, but now a part of me stayed present. It’s much harder to neglect words when they are coming out of your mouth.

“Watchers” was just the beginning. Through my teen-age years there followed at least two dozen more book recordings. My father hired my brother and sister, too. He claimed that he wasn’t trying to broaden our literary horizons; he just wanted to hear the books. Nonetheless, they broadened mine. An incomplete list of my own assignments includes mainstream fiction (“A Separate Peace”), fantasy (“The Fellowship of the Ring”), crime fiction (“The Grifters,” “You Play the Black and the Red Comes Up”), science fiction (“Dune,” “Ring Around the Sun”), and various anthologies.

Left to my own devices, I’m sure I would have found “The Fellowship of the Ring” and “Dune,” but I doubt that I would have picked up a novel like Jim Thompson’s “The Grifters,” the title of which meant nothing to me, and the cover of which bore an illustration of a simian-faced man, a morose woman smoking a cigarette, and a pair of large dice, perched atop a worrisome blurb from the Boston Globe that cautioned, “Strong meat.” I must have been thirteen or fourteen when I read the book, and the harsh, mendacious world it described startled me. The insane contrast between it and “The Fellowship of the Ring” was a pleasure in itself; to go from one to another was a form of teleportation.

The job was also excellent practice for writing. Closing my door and sitting at my desk echoed what my parents did each day, when they shut themselves in their respective offices and sat alone for hours on end. (Dad sometimes returned to work after dinner and kept on into the night. If, lying in bed on the other side of the house, I discerned the sinister bass line of one of the AC/DC LPs that he liked to listen to at jet-engine volume, I knew that he was revising.)

I was alarmed by the amount of time that my parents spent alone. I couldn’t understand how they could bear it. I thought being a writer must be not only the worst job in the world but the scariest. I remember loitering on the carpeted step outside Dad’s office, with Marlowe, our corgi, sprawled in front of his door. Marlowe was among the most gregarious of creatures, but if Dad shut the door he’d collapse into a bleak pile on the spot. His tragedy was my best opportunity to pet him, so I’d plunk down, too. In the background, the plastic tumult of Dad’s keystrokes came from inside the office. It occurred to me once, as I petted Marlowe and the rattle of keys went on and on, to wonder if my father was actually typing anything specific, or just making as much noise as he could to keep bad things away.

To my knowledge, no tapes of “Watchers” survive, though I do have my reading of “Dune.” It’s a lamentable document; I narrate, rhinal and breathless, like a telemarketer fighting to keep someone on the line. But I still record the odd book for my father as a gift. A few years ago, I undertook “War and Peace” as a Christmas present. It ended up being delivered a couple of Christmases late, and I committed crimes against Russian nomenclature that only God can forgive, but I believe it represented a major improvement in technique. I might have been a bad Alan Breck Stewart, but I had the right idea: when you read to someone else, it’s easier for them to absorb the language if you put a little character into the characters. You’re not calling from Resort Rewards Center. You’re reading about a pissed-off man with a sword.

Dad’s a much better reader than I am, though. He’s recorded a number of books for me over the years: novels by Louise Welch, Jon Hassler, Graham Greene. He doesn’t do many accents, but he’s terrific at shading certain voices, dampening the speech of a drunk, adding a touch of a sneer to an abrasive character. What he’s especially good at is the pacing—no surprise if you’ve read his novels. Those tapes and CDs are very special to me, warm and living. It’s a comfort to have a familiar voice there in the car, telling a story. I get why you’d be willing to pay for that.

Sourse: newyorker.com