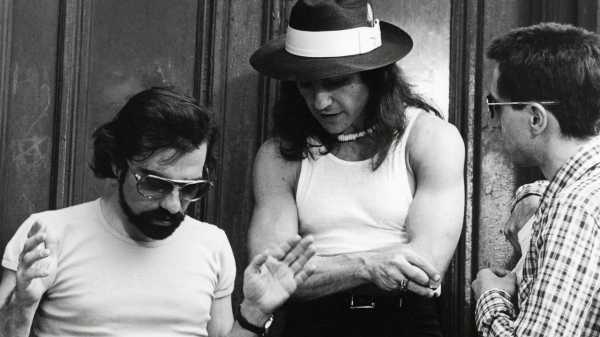

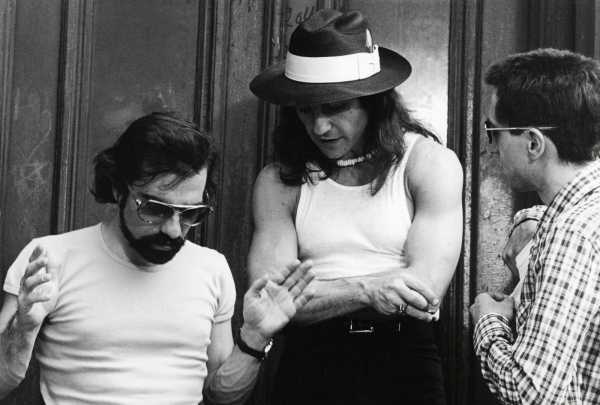

Martin Scorsese, Harvey Keitel, and Robert De Niro on the set of “Taxi Driver.”Photograph from Alamy

There’s something in the middle of Quentin Tarantino’s new book, “Cinema Speculation,” that made me want to kiss it on both the front and back covers. It’s an encomium to the actor Barry Brown for his performance in “Daisy Miller,” Peter Bogdanovich’s 1974 adaptation of Henry James’s novella. The tribute to Brown is not the most intricate or insightful part of a book that is often delightfully both, but it’s a heartfelt and melancholy memorial for a gifted, distinctive actor who died shockingly young, at twenty-seven, in 1978, by his own hand. There’s an awkwardness to Tarantino’s enthusiasm—he likens his grief to that of Frederick Winterbourne, the character whom Brown plays in the movie—that nonetheless conveys intensity and sincerity. In “Cinema Speculation,” Tarantino ranges widely through the movies of the nineteen-seventies that captivated him in his youth and that still inspire, fascinate, and haunt him. It’s a book of cinema-centricity and Tarantino-centricity that is nonetheless populated by a vivid array of characters—whether real-life ones, such as Brown, or ones seen in the movies—to whom Tarantino offers alluring moments in the spotlight.

There are three basic kinds of good nonfiction: the kind that results from consummately professional work, featuring thorough research, organizational clarity, analytical insight, wide-ranging knowledge, and writerly style; the kind that represents an outpouring of passionate affinity to the subject matter, a Virgil-like journey into otherwise inaccessible realms; and the kind that delivers the uniqueness of personal experience. “Cinema Speculation” has a foot in all three domains, and, since Tarantino has two feet, it makes for a lot of fancy footwork—which he pulls off, for the most part, with jittery, skittery energy. He tells the story of his destiny: of how, when he was seven, in 1970, his mother and stepfather began taking him to films that were wildly age-inappropriate. These films fascinated him, even frightened him, and he responded to them with an unusual curiosity. His mother could have left him with a babysitter, and he understood his side of the moviegoing bargain, which was to keep quiet and behave. As a result, he paid close attention to what he was watching, and he learned what adults got up to when they go out and the sorts of things that they found entertaining.

Barry Brown, Cybill Shepherd, and Cloris Leachman in a scene from “Daisy Miller.”Photograph from Getty

When young Quentin watched the Oscars broadcast in 1971, he’d seen all five Best Picture nominees (“Patton,” “M*A*S*H,” “Five Easy Pieces,” “Airport,” and “Love Story”) and knew well that his movie exposure—and his habit of telling his classmates in detail about what he’d seen—made him stand out. He stood out as well because his mother was dating a Black man named Reggie, who took him to see Blaxploitation films in predominantly Black neighborhoods. He cites their moviegoing habits as the bedrock of his cinematic destiny: “To one degree or another I’ve spent my entire life since both attending movies and making them, trying to re-create the experience of watching a brand-new Jim Brown film, on a Saturday night, in a black cinema in 1972.” The book is centered almost entirely on violent films, action films, horror films, the kinds of films that delighted the child Quentin and the teen Tarantino and that, to all appearances, are still—for better or worse—at the core of his cinematic universe.

“Cinema Speculation” is the work of a filmmaker whose knowledge of movies is prodigious, and who, by dint of his professional experience, can add the insights he has gained from inside the industry, along with interview access to many of the people whose work he writes about. That’s the perspective that informs the book and that raises it above what would in any case be an engagingly garrulous memoir. For instance, Tarantino’s consideration of “Bullitt” is centered on his interviews with the screenwriter and director Walter Hill, who was an assistant director on the film, and with Neile McQueen (known professionally, as an actress, as Neile Adams), Steve McQueen’s wife at the time it was made. Tarantino credits her “good taste and her keen understanding of both her husband’s ability and his iconic persona,” which he identifies as the decisive force behind McQueen’s choice of projects. These interview subjects talk about how McQueen, unlike other actors, would reduce his own dialogue on-set, handing his lines to other actors, knowing that what made his stardom was essentially silent.

Tarantino closely and lovingly scrutinizes the work of character actors, and often makes them the fulcrum of his analysis. He treats “Dirty Harry” as the seminal serial-killer movie and spotlights the performance of Andy Robinson, in the role of the Scorpio killer, as the reason for the movie’s historic effect. He looks closely at John Flynn’s “Rolling Thunder” (which he calls “the best combination of character study and action film ever made”) and tells the story of how, at the age of nineteen, he met and interviewed Flynn. He offers overarching historical views on the changes that took place in Hollywood in the late sixties and early seventies, and the overlapping generations of new directors who worked there (and the underlying cultural differences that marked their movies). In his discussion of Sylvester Stallone’s career, he devotes rapturous attention to both “The Lords of Flatbush” and “Paradise Alley,” along with a recollection of the cultural prominence, in the mid-seventies, of fifties nostalgia and the appreciation (strengthened by film-historical details) of the epochal influence of “Rocky.” And he looks gratefully at the career of the critic Kevin Thomas, whose coverage of genre films in the L.A. Times Tarantino considers crucial to the course of movies in the seventies and beyond.

The book’s title is more than rhetoric. The best sections involve Tarantino’s counterfactual speculations, based on his copious reading of books and articles about Hollywood, his familiarity with early versions of scripts, his acquaintance with Hollywood notables, and his critical insights regarding the careers and passions and inclinations of these notables. In the long chapter on “The Getaway,” there’s a great riff on Peter Bogdanovich being attached to the project before Sam Peckinpah was signed to direct it, an extended discussion of how Ali MacGraw came to co-star in it with McQueen and the effect that her performance and her persona had on its reception; a careful look at how the casting of supporting roles determines the movie’s tone as well as its effect on viewers; and a detailed study of the differences between the film and the novel, by Jim Thompson, on which it’s based. The book’s intellectual engine is its auteurist perspective. As a director as well as a virtual critic, Tarantino delves deep into the kinds of decisions that directors make, both at the macro level of major career moves and the micro level of behavioral details and camera angles, with an absorbing acuity.

Steve McQueen and Ali McGraw in “The Getaway.”Photograph from Getty

The extended portraiture of Brian De Palma stands out for the idiosyncrasy of its insights, which spill over into a detailed study of “Taxi Driver,” which De Palma was originally supposed to direct. Tarantino muses on what kind of movie would have resulted, and how De Palma’s entire career may have shifted as a result. (It wouldn’t be Tarantino if the discussion of “Taxi Driver” didn’t pivot on race—he’s obsessed with the fact that the movie’s pimp, played by Harvey Keitel, is white, and he assumes, for reasons that he details at length, that, had De Palma directed it, the pimp would have been Black. It wouldn’t be Tarantino if the book didn’t include the N-word—albeit in quotes.) The book’s concluding chapter is an act of duty and penitence, a reminiscence of a man named Floyd Ray Wilson, a Black man who dated the best friend of Tarantino’s mother and, years later, rented a room from Tarantino’s mother. Wilson was a post-office employee and a movie fanatic who went to movies with the teen-age Tarantino; he also wanted to be a screenwriter. Mentioning a script for a Western that Wilson showed him, Tarantino belatedly credits him with inspiring “Django Unchained.”

“Cinema Speculation” is consistently engaging; with its zinging and zipping observations, its casual opinion-flinging, and its sharp-edged divisions of personalities and eras, it seems designed to arouse fruitful arguments. Like the experienced fictioneer that he is, Tarantino creates images and stories and scenes, tells tales that entice and bewitch even as they invite the same sort of criticism that his movies do. Above all, “Cinema Speculation” is a vision, in motion, of a Hollywood-centric mind. It’s like seeing a watchmaker take apart other craftsmen’s watches and show how they function and why they have marketplace appeal, but never looks at chronometry over all, its place in the world, the existence of other kinds of timepieces, or whether and why people even need such watches anymore. It tells the story of being, in effect, born as an insider (even without an actual professional or industry portfolio), coming to consciousness by way of Hollywood movies. Tarantino displays an extraordinary understanding of how things work; his responsiveness to the industry’s traditions of script construction, character psychology, and genre frameworks is the heart of the book—as it is of his movies. He’s so deep in the conventions that he has gone from loving them, studying them, and revising them to being trapped in them. If, as Tarantino has said, he’s going to make just one more film, this book may well be the clearing of the ground before his great escape—the reckoning of his lifetime on the inside before breaking out. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com