Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

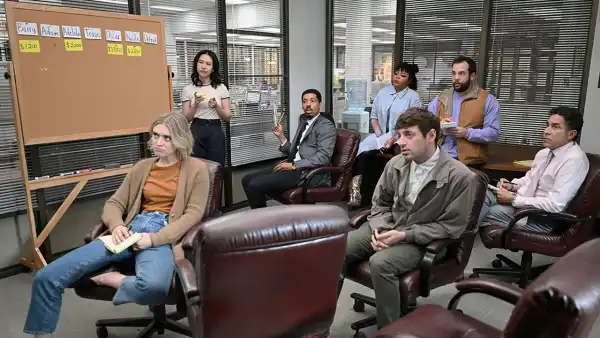

The fictional newspaper at the core of the new comedy, “The Paper,” the Toledo Truth Teller, dwells in the memories of its former glory. Fifty years prior, the daily had a payroll of more than a thousand individuals, with a hundred reporters committed only to Ohio state politics; presently, it occupies merely a segment of the towering Romanesque Revival edifice that shares its namesake. Mare (Chelsea Frei), its most promising staffer, spends her time populating the subsequent edition’s cover with syndicated articles penned by external reporters about distant locations. Local reporting is now limited to scores from high-school sporting events. “I’m not even certain it’s a legitimate newspaper,” Mare confides in Ned (Domhnall Gleeson), the arriving editor-in-chief, who, upon starting, pledges to prevent the Truth Teller from “collapsing in the style of an aging smoker’s lungs.” Unseasoned and impractical, Ned introduces two cringe-worthy items to the newsroom: a typewriter and a firm conviction of a promising future.

Debuting this week on Peacock, “The Paper” was co-created by Greg Daniels, who is celebrated for his adaptation of Ricky Gervais’s “The Office” for viewers in America. Like its antecedent, this program is presented as a mockumentary, with the documentary crew trailing Ned’s time revealed to be the very same one that chronicled the previous series. (The two also feature a shared, minor character, the bookkeeper Oscar Martinez—among a number of nods that feel like transparent attempts to woo fans.) Though humorous, the franchise has consistently been imbued with a distinct sense of post-industrial weariness: “The Office” unfolds in a paper-supply business, where the staff are aware that their vocations are soon to be outmoded. Later seasons focused on the shaky financial state of the enterprise, which, by the opening of “The Paper,” has been absorbed by a bigger entity whose leading commodity is toilet tissue. The Truth Teller, too, is sinking.

Unlike Michael Scott, the tyrannical boss from “The Office,” Ned is a thoughtful superior—though one prone to virtue signaling and affected self-denial. (As a matter of fact, Ned is more akin to a different Daniels character: Leslie Knope from “Parks and Recreation,” an enthusiastic, formal reformer who, when distressed, succumbs to the mania that lurks below the surface.) Nevertheless, bringing the Truth Teller back to life turns out to be a difficult undertaking. Corporate leaders refuse to support Ned’s revamp of the paper, compelling him to seek reporters from the business departments: accountants, the advertising person, the subscription director, even a toilet-paper sales representative—basically, anyone willing to give a handful of hours weekly. Although Mare flourishes quickly under his direction, the others trail dumbly behind, employing journalism as justification to confront a former love interest, or being deceived by some teenagers into writing a naive report about an outlandish youth trend. Despite Ned’s aspiration of “cultivating sources over whiskey in a smoky tavern,” his initial significant exposé stems from an ethically questionable scheme at a mattress retailer.

“The Paper” surpasses “The Office” in its allusions to decline. But I discovered my focus wandering from its nostalgia for Watergate-era journalism to my own longing for early-2000s network comedies. During that time, the demands of broadcast TV put firm structures on comedy composition, yielding such contemporary mainstays as “Arrested Development,” “30 Rock,” and “The Office” at its best—each distinguished by quick characterizations and remarkably dense humor. Conversely, “The Paper”’s sluggishness typifies the pacing dilemma of the streaming age. A large portion of the cast is underdeveloped; an improbable misconception concerning Mare’s sexual orientation is somehow extended into a plotline that lasts for multiple episodes. After some time, the realization that the Truth Teller’s parent corporation is named Enervate starts to appear somewhat unsubtle.

On occasion, “The Paper” presents a welcome flashback to the apex of the workplace sitcoms of the early millennium. The greatest asset of “The Office” was its characters: the program encouraged you to relish time with the sort of individuals you’d generally be relieved to leave at five P.M. The most memorable character in the new ensemble is Ned’s second-in-command, the flamboyant, attention-grabbing Esmeralda (Sabrina Impacciatore), who refers to herself in the third person as “a single mother, even though you’d never know given that her physique is insane.” Esmeralda, who is truly proud to generate the kind of celebrity-focused clickbait that Ned desires to abandon, is a former participant on reality television, and it’s appropriate that she, surpassing her peers, is aware of how to perform for the cameras: she likens her colleagues to lobsters, cockroaches, and copulating dogs, including bold physical impressions. (I would eagerly watch her on “The Real Housewives of Toledo.”) Unsurprisingly, she is the least-liked individual on the staff. A subplot in the middle of the season in which a romance scammer targets lonely women, including Esmeralda—and wherein an office pool materializes trying to pinpoint the precise amount of funds she’s forfeited to the plot—amounts to the show’s first brilliant episode by first upending, then enriching, her connection to the remaining members of the newsroom.

“The Paper” endeavors to extract amusement from the disparity between the present state of journalism and its potential. It captures aspects of the modern media landscape appropriately, such as when a corporate manager seeking a revenue stream inquires, “What is our Wirecutter? What is our Wordle?” or when Ned articulates that composing on deadline resembles “having homework every single day, indefinitely, until the newspaper fails and I am unemployed.” However, white-collar work has also changed in other ways in the decade since “The Office” concluded. Efforts to integrate these shifts, including a weak, early joke regarding how Ned has not been MeToo’d, are awkward at their best. Mare’s unconvincing declaration that “A.I. will never supplant me” is similarly difficult to accept as comedy. While one might like to support the underdog, it is undeniable that the triumphs of the revamped Truth Teller are minimal. “The Paper,” like the publication it features, is sporadically charming—and inevitably eclipsed by what preceded it. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com