The problems examined in Lacombe, Lucien are still with us 50 years later.

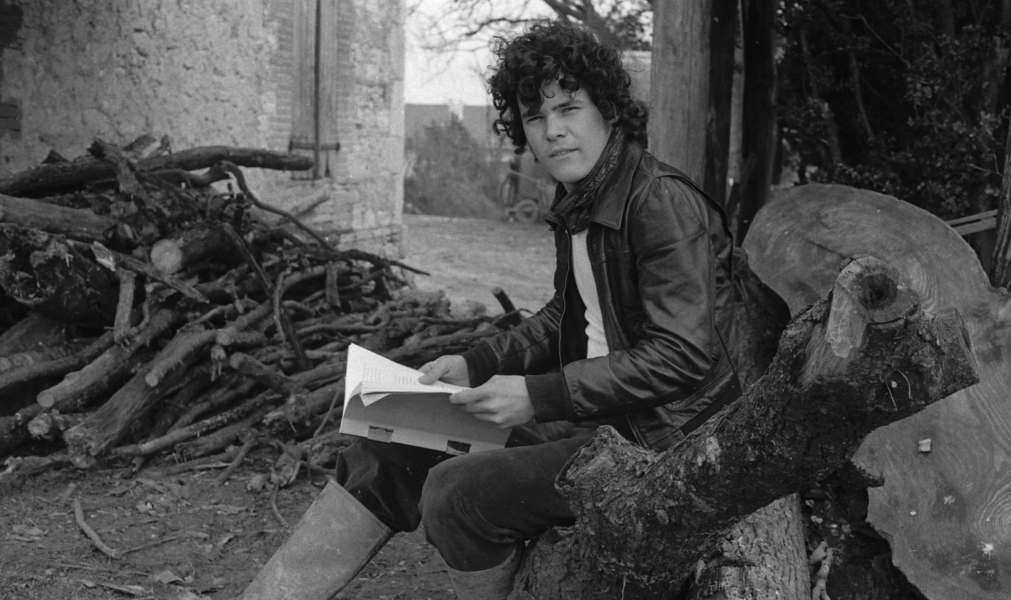

Credit: WikiMedia

The French Resistance looms large in our collective memory of the Second World War. The chain-smoking, beret-clad partisan is a stock character in countless movies and TV shows; more soberly, the genuine heroics of the maquis have been chronicled in thousands of books, articles, and documentaries. Such has been the prominence of these portrayals that one could be forgiven for supposing that a large proportion of Frenchmen—perhaps even a majority—spent the war fighting their Nazi occupiers.

Yet historians estimate that, at most, 2 percent of the population was involved with the Resistance. From the fall of France in 1940 until her liberation by the Allies in 1944, collaboration—whether with the German military administration in the north or the puppet Vichy regime in the south—was a vastly more common response. There were understandable reasons for this: Active resistance carried with it the risk of torture and death, and even passive forms of noncompliance could lead to serious social and material consequences. Moreover, France was still reeling from the totality of its “strange defeat,” which seemed to have as much to do with the internal weakness of the Third Republic as the power of the German war machine.

Under such circumstances, many people chose to go along to get along. Some held high positions with the occupation authorities, informed on friends and neighbors, and even donned Nazi uniforms to fight on the Eastern Front. Others merely continued in their careers as postal workers or government clerks, sold goods to German soldiers, or enrolled their children in “patriotic” youth groups. (Whether or not such actions should be described as collaboration is perhaps an open question; certainly there was a spectrum).

When the tide eventually turned, and Allied tanks drove the Axis first from French soil and then into historical oblivion, there was left the tricky question of how to deal with this sordid aspect of the country’s wartime experience. The first months after liberation had seen Resistance partisans effect a kind of impromptu reckoning in hundreds of towns and cities across the country, and the chief collaborators—Philippe Pétain, Pierre Laval, etc.—had been duly tried and punished.

That done, there was little appetite for more thoroughgoing purges. After all, many of the civil servants who had worked for Vichy were now needed to staff the bureaucracy of the new Fourth Republic, and the nation—embarking on the period of economic recovery that would become known as les trente glorieuses—preferred to lean into its future rather than dwell on painful episodes from its past. When the topic was broached, the usual reaction was a kind of fatalism, in which collaboration (at least of the rank-and-file variety) was understood as a passive response to overwhelming outside forces. There were even some who saw Vichy as a lesser evil, a distasteful but in some sense defensible way of precluding outright Nazi rule over the whole country (this, not incidentally, was the argument deployed by Pétain and Laval at their trials).

But with the sociopolitical ferment of the ’60s and ’70s came a new willingness to challenge this convenient postwar orthodoxy. Two works exercised a particularly strong influence: Marcel Ophüls’s 1969 documentary The Sorrow and the Pity, which undermined France’s image of itself as a “nation of resisters” by vividly showing the extent of collaboration in a single, fairly typical city; and Robert Paxton’s 1972 book Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940–44, a meticulous and brilliant history of the Vichy years that centered French agency rather than Nazi coercion. (“Collaboration,” the book’s thesis ran, “was not a German demand to which some Frenchmen acceded…. Collaboration was a French proposal.”)

It was against this backdrop that, 50 years ago, Lacombe, Lucien made its theatrical debut. Masterfully directed by Louis Malle (perhaps best known in the U.S. for making My Dinner with Andre) and scored by the great jazz musician Django Reinhardt, the movie follows the short career of Lucien Lacombe, a wayward teenager who becomes a combination errand boy/hit man for the Vichy secret police.

We first meet our protagonist in June 1944, when he is living on his family’s farm in southwestern France. Despite the loveliness of his surroundings—Malle shot on location in Figeac, a medieval Occitan village—home life is no idyll for Lucien. His father went missing in the war, and his mother’s new beau has moved in and wants to clean house. The teen’s first thought is to join the Resistance, but he is turned down by the local commander. “You’re too young,” he is told, “and we have enough like you.” Milling around town dejectedly, Lucien stumbles into the headquarters of the Carlingue—French auxiliaries to the Gestapo—who find his naïveté charming and his indiscriminate appetite for excitement useful.

Unsurprisingly, this office doesn’t exactly pull in the best and the brightest. Its members include a dissolute and disinherited aristocrat, an over-the-hill bicycle racer, and a police inspector drummed out of the prewar force. They do the job more for its perks—power, the odd bit of cash, opportunities to inflict pain—than from any kind of ideological commitment. Indeed, the group’s only zealous fascist is seen as something of an oddball by his confreres, who crack dirty jokes about Pétain and use his portrait for target practice.

Lucien himself takes to this new line of work without any misgivings; the bullying and violence interest him as much as the champagne and fancy clothes. This, in fact, is one of the remarkable things about this movie—Malle’s protagonist is utterly incapable of any kind of ethical or ideological engagement. He’s neither innately evil nor especially brutish, although he does have a thing about shooting animals (especially rabbits). Rather, he is deeply, profoundly stupid. He puts one in mind of DiCaprio’s character in Killers of the Flower Moon, albeit less voluble and more believably characterized. Even his romantic attachment to a Jewish girl—the daughter of a tailor who is being extorted by one of Lucien’s colleagues—fails to provoke any kind of self-reflection until it’s far too late. And his stupidity doesn’t only impose moral costs. The very night he joins the Carlingue, the radio is broadcasting a report on the Allied landings in Normandy; as it turns out, June 1944 was a less than propitious moment to throw one’s lot in with the Axis.

Subscribe Today Get daily emails in your inbox Email Address:

The deepest clue to Lucien’s motivations comes when he is assigned to guard a captured Resistance partisan. The prisoner, whose interrogation has been mercifully interrupted, tries to talk Lucien into setting him free. Meeting silence, he finally appeals to his captor’s sense of patriotism. “So you’re with the Germans. A young Frenchman like you! Aren’t you ashamed?” This gets a response: Lucien tapes the prisoner’s mouth shut. “I don’t like people talking down to me,” he says.

Of course, Lucien is an extreme case. Much more typical is the experience of his mother’s boyfriend, Laborit. Before D-Day, he appears to be a solid supporter of Vichy, speaking contemptuously of the local Resistance partisans. But as the months pass, and a German defeat appears more and more likely, Laborit comes all the way around, denouncing as treason Lucien’s collaboration (in this regard, Laborit embodies the attitude of the attentiste, that recurring figure in French history—think Talleyrand—who can survive and thrive amidst endemic instability).

However unrepresentative the specifics of Lucien’s trajectory, the motives that set him on that path—the desire for agency and belonging, the temptation to indulge one’s animal appetites—were and are universal. Or, as one French statesman (and Resistance veteran) put it after the war: “There are certain tendencies and habits which, when they are fired, fed, or stimulated, crop up like weeds… and so we must always be on the defense.” As ever more of the world falls under the shadow of war—and passion increasingly strains the bonds of affection here at home—it is precisely this insight that makes Lacombe, Lucien as essential today as it was five decades ago.

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com