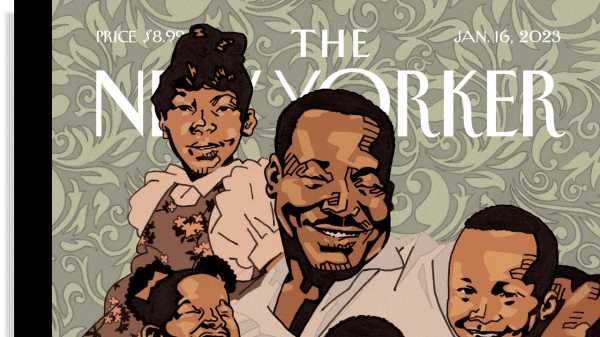

The campaign to establish a federal holiday in honor of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., began soon after his assassination, in 1968, but it wasn’t signed into law until 1983, and it wasn’t observed in all fifty states until 2000, thirty-two years after his death. By now, King’s name and image are familiar to every American. Perhaps less familiar is the man himself. In his cover for the January 16, 2023, issue, his first for the magazine, Pola Maneli depicts the civil-rights hero in a personal context, surrounded by his children. I recently spoke to the artist about King’s legacy and the difficulty in recognizing the humanity of our heroes.

You grew up in South Africa. As a child, how did you encounter Martin Luther King, Jr., and what does he mean to you now?

I was first introduced to him as an orator, so as a kid I didn’t really know anything about him other than the fact that he gave really stirring speeches. I feel like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., along with Nelson Mandela, was one of a few figures that young Black boys in South Africa were encouraged to emulate, even though much about the way they were presented to us was heavily decontextualized and redacted.

As for what he means to me now, I would say that he has helped shape my ideas of how one can participate in politics, as a model for civic engagement. Dr. King showed me how an invested individual can make important contributions toward radical change.

Why was it important for you to highlight Dr. King’s role as a father, instead of depicting his activism and accomplishments?

My first impulse was to try to depict him in an explicitly radical or assertive light as a response to how heavily sanitized his politics have become in the decades since his passing. But, while I definitely think that’s a valid impulse, as that part of his life should be highlighted more often, I quickly became uncomfortable with the thought of enlisting my work and his memory in a proxy battle with structural racism. Part of the problem with memorializing people as symbols and ideas is that we risk obscuring parts of their humanity. The challenge of portraying as much of that humanity as possible really excited me, and I couldn’t imagine an environment where that would have been on display more than in his moments as a father. So I set out to create a portrait of him that felt as candid and tender as the way he comes through in some of Michael Ochs’s photographs of his family.

You worked in advertising, academia, and education before landing on illustration. How do your past experiences in those fields inform your work now?

The writing I was exposed to as a postgrad research assistant did a good job of keeping some of the cynical elements of advertising in check. However, the pragmatic limitations I experienced in advertising also keep whatever utopian idealism I may have picked up in academia in check as well, so, believe it or not, I’d say that those two experiences complemented each other quite well. Neither of them compared to the fulfillment that teaching gave me, though. Education taught me how to evaluate my work more honestly, and being with students really reinvigorated my love for drawing—so much so that I had to quit teaching to pursue freelancing full time. I hope to go back to teaching one day, but, first, I feel I have much more to do as an artist.

In a world that is awash with so many images, what do you think the purpose of art is?

I’m interested in creating work that I personally find evocative; if within that there’s space for some kind of critical thought that can be presented in a graceful way, then that’s even better. I think there’s only so much one illustration can do, but, if it can provide a viewer with a little bit of refuge from the world, then that’s a success, in my opinion.

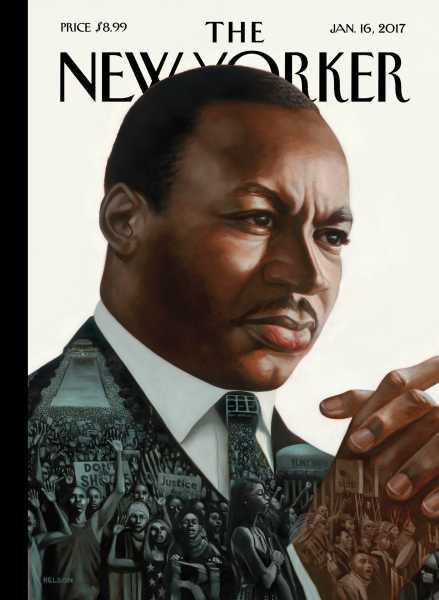

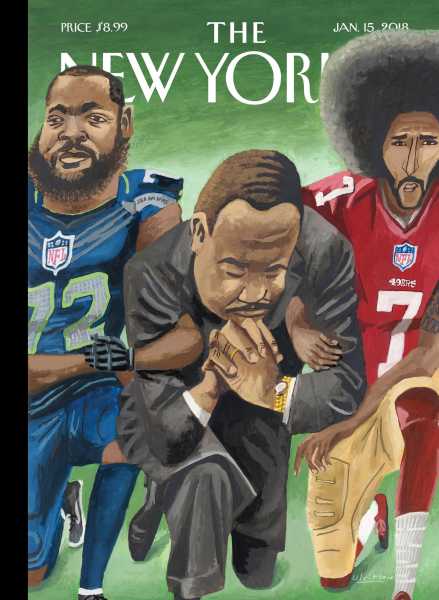

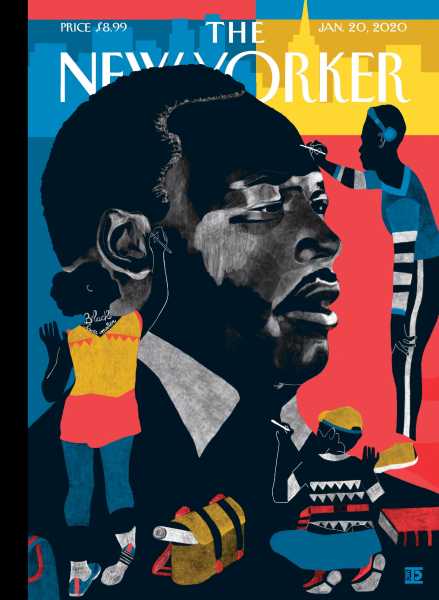

See below for other covers on Martin Luther King, Jr.:

“After Dr. King,” by Arthur Getz

“In Creative Battle,” by Mark Ulriksen

“Portrait of History,” by Diana Ejaita

Sourse: newyorker.com