The expression “face to face” suggests both intimacy and confrontation, a reckoning of sorts, whatever its purpose or tone. Currently, at the International Center of Photography, the phrase serves as the appropriately expansive title for a three-person exhibition whose focus is the charmed and charged phenomenon of the artist portrait. The generous selection of works, curated by Helen Molesworth, features contributions from the artist-filmmaker Tacita Dean and the photographers Brigitte Lacombe and Catherine Opie. The formidable subjects—including Richard Avedon, Maya Angelou, John Waters, and Patti Smith—are themselves accustomed to holding the reins of representation, which isn’t to say that they’re not game, at least for a moment, to let go. Though, in truth, the nuance and depth of the work on view speak more of engagement than of surrender.

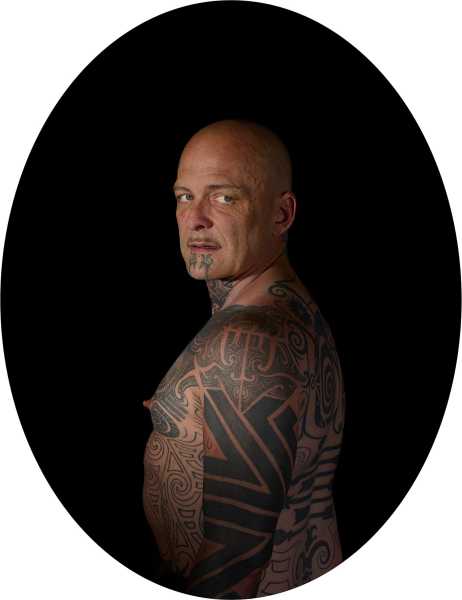

“Kerry,” 2017.Photograph by Catherine Opie / Courtesy Regen Projects / Lehmann Maupin / Thomas Dane Gallery

The works, mostly large-scale, are arranged in close proximity—creating something like an imaginary meeting of the minds among likenesses—and underscored by wall-label texts that include quotations from the subjects reflecting on their own methods or self-conceptions, like thought bubbles. “Writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people . . . It’s an aggressive, even a hostile act,” Joan Didion asserts in the text accompanying Lacombe’s frontal black-and-white image of the author with a wide-eyed gaze, her hands raised to her mouth, as though in gasping reaction to something the photographer has just said. “The challenge is always how to handle the way light falls on a black object without allowing it to destroy the form, but rather merely reveal it,” the smiling painter Kerry James Marshall muses in the label for Opie’s “Kerry,” from 2017, in which Marshall emerges from a black background—or dissolves into it. And words are integral to Dean’s piece “One Hundred and Fifty Years of Painting,” from 2021, a looping film that lingers on the painters Luchita Hurtado and Julie Mehretu as they sit talking. It is, perhaps, an apt emblem for “Face to Face.” Taken as a whole, the show is an extended conversation—conspiratorially murmuring, fruitfully clashing—across time and space.

The artists’ subjects also overlap. David Hockney appears, in his studio, in one of Dean’s uneventful, whirring projections (the 16-mm. films are not transferred to video) and also in one of Opie’s studio images, part of a long-running portrait series of subjects set against moody, black backgrounds. Kara Walker is portrayed in profile by both Opie and Lacombe, in similar compositions. In each image, Walker bears approximately the same expression, but, in Opie’s velvety gloom, she is, per Marshall, merely revealed. Lacombe’s vision of Walker is differently beautiful—amply lit and forthright.

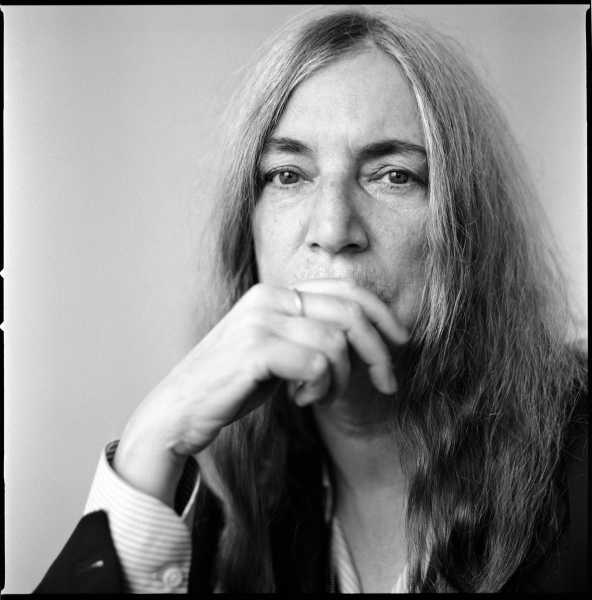

“Patti Smith,” New York, N.Y., 2014.Photograph by Brigitte Lacombe

The most striking contrast on view, though, lies not in the treatment of faces and bodies but rather in the treatment of their settings. Inherent to Dean’s verité style is a sense of place, a world populated by furniture and things. Lacombe, too, when she is not shooting commissioned portraits, is a sharp observer of naturalistic mise en scène. Echoing Dean’s contemplative depiction of Hockney, “Lee Bontecou, Orbisonia, PA, 2003,” a wide view of the sculptor Lee Bontecou in her shacklike workspace, gives the viewer an almost granular sense of both ambience and craft. Here, the tools and miscellanea of art-making are as much a part of the portrait as the subject’s unaffected grin or solid stance.

“Vaginal Davis,” 1994.Photograph by Catherine Opie / Courtesy Regen Projects / Lehmann Maupin / Thomas Dane Gallery

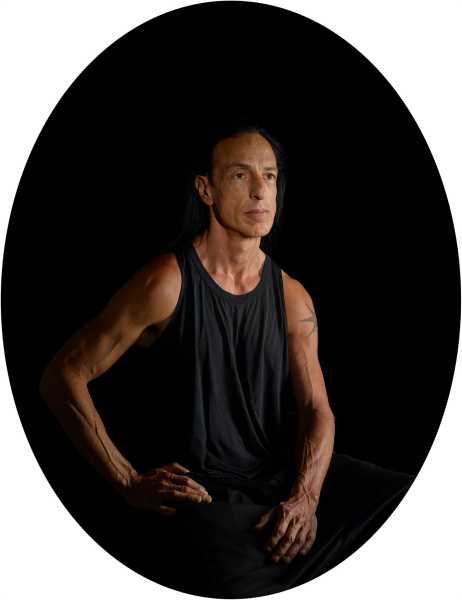

Opie takes the opposite tack, isolating her figures, suspending them in mythic space—a voluptuous nowhere—to iconographic effect. Early in Opie’s career, before she turned to deep black, she depicted the characters of her queer orbit against colored backdrops, referencing European traditions of aristocratic portraiture and religious painting. A full-length portrait of Vaginal Davis, from 1994, presents the visual artist and performer nude but for high-heeled slides with ankle socks, a bright lime merkin, and a matching wig. That description may sound funny, but the image is not: Davis is dolled-up but defiant, an altarpiece heroine in azure space. The pose is contrapposto; her hands, behind her back, look as though they might be tied. Absurdly, but gravely, Davis gives us Saint Joan at the stake.

“Ron,” 2013.Photographs by Catherine Opie / Courtesy Regen Projects / Lehmann Maupin / Thomas Dane Gallery

“Mary,” 2012.

“Rick,” 2017.

Modernism reframed the Western notion of the portrait, shifting its goal from the representation of status to the reflection of some individual psychological truth, yet these images expose the power relations and assumptions behind that newer approach, too. That the people depicted here are artists makes all the clearer the essential volatility of the pact upon which ethical portraiture depends: at any time, the sitter might seize control. Indeed, some of these images may memorialize the surprising (or anticipated) moment when the tables turned. Here, “face to face” implies not just closeness but a negotiated reciprocity, a mirroring, a commitment to give and take.

“Maya Angelou,” New York, N.Y., 1987.Photographs by Brigitte Lacombe

Sourse: newyorker.com