Each of the five Patrick Melrose novels, by Edward St. Aubyn, has the weight of a prose poem, the span of a novella, and the structure of a vignette. St. Aubyn’s superbly controlled prose extracts elegance from the narrative malformations of real life, and the books star the wittiest junky in all of English-language literature. The five-episode miniseries “Patrick Melrose” (on Showtime, premièring Sunday) is both a mash note and a lavish footnote to its source material.

Benedict Cumberbatch plays Patrick, a well-born Englishman addicted to a number of things, including shooting heroin, shooting cocaine, and needles themselves. (In one passage, Patrick poses a question about syringes to himself and to the universe: “What other form of self-division was more directly expressive than the androgynous embrace of an injection, one arm locking the needle into the other, enlisting pain into the service of pleasure and forcing pleasure back into the service of pain?”) Patrick is addicted, above all, to self-annihilation—suicide on the installment plan—though he would likely scorn that phrase as trite, in the cruellest possible terms, because he is also addicted to snobbery.

All of this comes from an awful patrimony. Patrick’s father began raping and beating him when the boy was young. (In the book, the abuse begins when the boy is five years old. In the TV series, it becomes eight, in what feels like an impossible attempt to spare the viewer some fraction of anguish.) “Self-division” points toward to the detachment of Patrick’s mind from his body. During the first of his father’s assaults, the boy suffered an out-of-body experience and felt himself disappear into the body of a gecko that happened to climbing the wall above his traumatized head. As an adult, he takes drugs in an effort to escape himself, which always fails—unless the problem is really that he succeeded, at some point, and now cannot find his way home.

The second novel, titled “Bad News,” becomes the first episode. Patrick, in his early twenties, flies from London—where he is carrying on an imitation of life as an independently wealthy smack head—to New York City, where his father has died. In narrative terms, it is very straightforward: Patrick checks into a swank hotel, swears to seize the death of the monster as an occasion for getting clean, bargains his way to shopping for quaaludes and speed in Central Park, and slips to the edge of oblivion. The episode resembles John Self’s drinking binge in Martin Amis’s “Money,” as redrafted by Lou Reed. The rising action takes the form of a downward swirl.

On the page, St. Aubyn puts this over with his perfectly lucid descriptions of chaotic mental states, a triumph of style that illuminates the murk of Patrick’s psychology. Onscreen, Cumberbatch (playing scenes directed by Edward Berger and written by David Nicholls) compellingly froths, hops, and slithers with junk sickness, giggles with mania, nods off, twitches on, and writhes in revulsion. But the actor’s dazzle distracts from the character’s grotesque situation rather than illuminating it. The part is a showcase, and the performance is showy; it left me acutely aware of watching something extremely actorly. Still, it is an extreme pleasure to see Patrick, feeling the quaaludes come on while a family friend tries to extend condolences about his father, excuse himself to ooze down a hallway, careening like a beast from his own hallucinations.

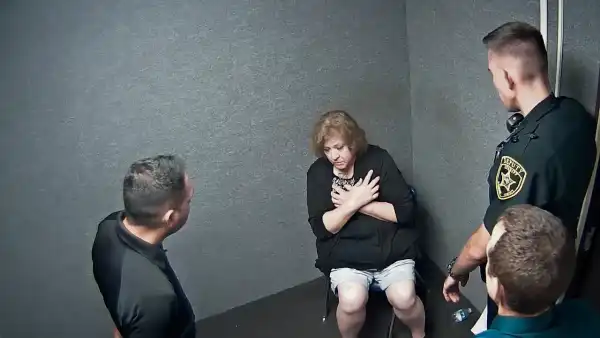

My qualified admiration for “Patrick Melrose” is based on viewing three of its five episodes. The second, adapted from the first book and titled “Never Mind,” describes the day the abuse began. The adult Patrick crops up only to punctuate it, in short scenes where he trembles in withdrawal, with the story of his formative trauma rising up like a pain no longer numbed. The addled behavior is left to Patrick’s father (played by Hugo Weaving, with a lot of silent seething and patient savagery) and mother (Jennifer Jason Leigh, bringing maximum wooziness to the role of an heiress hiding from her husband in a fog of pills and cognac).

The third episode, titled “Some Hope,” returns to Cumberbatch as a drug-free, thirty-year-old Patrick, and the actor follows his earlier pyrotechnics with simmering wryness and low-key self-loathing. It seems possible that he’ll stay clear of drugs, but his identity as a toff is a fate that he cannot escape. He suffers to go down to the country for a grand party full of scheming, snobbing, toadying, and one-upmanship. A royally tedious Princess Margaret, played by Harriet Walter, is seen to humiliate a fellow-guest with a sadism that would stir the heart of Patrick’s father, if he had one. Of the countless drugs abused here, class status is the nastiest one.

Sourse: newyorker.com