Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

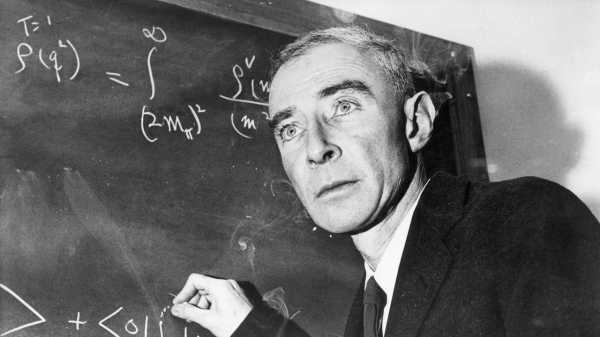

“Architect of Atomic Bomb Cleared of ‘Black Mark.’ ” That was the headline last December 18th, when the Times ran a long story on page 16 reporting that Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm had “nullified a 1954 decision to revoke the security clearance of J. Robert Oppenheimer, a top government scientist who led the making of the atomic bomb in World War II but fell under suspicion of being a Soviet spy at the height of the McCarthy era.” Granholm had issued a press release explaining that her department had been “entrusted with the responsibility to correct the historical record and honor Dr. Oppenheimer’s ‘profound contributions to our national defense and scientific enterprise at large.’ ” She said that she was pleased to announce the nullification.

The Times’ veteran reporter on things nuclear, William J. Broad, went on to summarize Oppenheimer’s life story and his downfall at the height of the Cold War: “Until then a hero of American science, he lived out his life a broken man and died in 1967 at the age of 62.” But, even in 1954, it was clear to most readers of the trial transcripts, leaked to the Times that spring, that the security hearing was a kangaroo court and that Oppenheimer had been publicly humiliated for political reasons. The “father of the atomic bomb” had to be silenced because he was opposing the development of the hydrogen “super” bomb. Ever since, historians have regarded him as the chief celebrity victim of the national trauma known as McCarthyism.

So why now, sixty-eight years after the infamous security hearing, and fifty-five years after Oppenheimer’s death, did the Biden Administration find the courage to do the right thing? Governments rarely apologize for their errors. How did this decision happen? True, the director Christopher Nolan has a major motion picture coming out this summer called “Oppenheimer.” But, contrary to popular myth, Hollywood’s influence in Washington is limited, particularly when it comes to the nuclear-security establishment.

Here is the wholly improbable story.

In 2005, Martin J. Sherwin and I published “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer.” Marty had worked on the biography for twenty-five years. I was brought aboard the project only in 2000. In 2006, the book won the Pulitzer Prize, and Marty was inspired by the notion that perhaps we could sue the government to revoke the 1954 decision. We wrote a four-thousand-word memo delineating how the Atomic Energy Commission, or A.E.C., had violated its own regulations governing security reviews. Among a long list of transgressions, they had illegally wiretapped Oppenheimer’s home and the office of his lawyer during the course of the security trial. Nothing incriminating was discovered. They allowed the three-member security panel access to Oppenheimer’s F.B.I. files, which ran to several thousand pages—but denied his own lawyer a security clearance, so he was not allowed to read the material being used selectively against his client. They blackmailed otherwise friendly witnesses to turn against Oppenheimer.

Armed with this catalogue of abuses, we approached a senior partner at WilmerHale, an influential Washington law firm, and persuaded him to take on the case pro bono. A young associate was assigned to research whether there was any legal recourse in the courts. Three months later, we got a phone call from the firm, explaining that it had to drop the matter due to personal objections from one of its partners, the late C. Boyden Gray, who had formerly served as White House counsel during the Presidency of George H. W. Bush. Washington is still a small town, and, as it happens, Gray’s father was Gordon Gray, the man who had chaired the three-member security-hearing panel that ruled against Oppenheimer.

Some months later, Marty Sherwin and I were at a crowded book party in Georgetown, at the home of William Nitze, a son of the late career politician Paul Nitze. Across the room, I pointed out to Marty, stood Boyden Gray. Marty marched up to Gray, introduced himself as Oppenheimer’s biographer, and proceeded to explain why what Gray’s father had done in 1954 was a travesty. Boyden Gray took offense, and they argued vehemently for a few minutes. No blows were landed, but Marty walked away pleased that he had spoken truth to power.

By this time, we had been advised by other lawyers that, separate from Boyden Gray’s objections, they had come to the conclusion that the courts could not be used to reverse the 1954 decision. The lawyers advised that such a reversal could only be achieved by executive order, probably by the President himself. (WilmerHale did not respond to requests for comment).

Early in 2010, we therefore approached the Obama White House. Fortuitously, the newly appointed White House counsel was Robert Bauer, who happened to be one of my high-school friends from Cairo, Egypt, where both of our fathers were stationed as Foreign Service officers in the nineteen-sixties. Marty and I drafted yet another memo making the argument for nullification and sent it to Bauer—and he was sympathetic. Bauer encouraged us to get a few senators or historians to sign a letter urging nullification.

Without further prompting, we soon learned that Senator Jeff Bingaman, Democrat of New Mexico, had sent a twenty-page memo on June 14, 2011, to Obama’s Secretary of Energy Steven Chu. Bingaman’s letter, which paralleled many of our own arguments, was drafted by a member of his staff, Sam Fowler, and marshalled a powerful legal case. But Secretary Chu declined to act. Bingaman retired from the Senate, in early 2013, and was replaced by Senator Martin Heinrich.

Marty and I later persuaded Heinrich to write a letter to Obama’s new Energy Secretary, Ernest Moniz, who was himself a trained physicist and someone whom we thought would be aware of, and sympathetic to, the Oppenheimer case. But in response to Heinrich’s pleading that he “issue a declaratory order vacating the decision,” Moniz offered bureaucratic pablum, saying merely that he was “keenly aware of Dr. Oppenheimer’s unquestionable scientific contribution to U.S. national security.” Moniz reported that, on the advice of his chief counsel, he could not reinstate Oppenheimer’s security clearance. (Moniz did not respond to a request for comment).

Not until the spring of 2016 did we get some momentum for our redemption campaign. On March 4, 2016, Marty and I drafted a two-page appeal to President Obama, asking him to overrule Moniz. Simultaneously, I reached out to an old friend, Tim Rieser, who was a longtime aide to Vermont’s Democratic senator, Patrick Leahy. I explained the issue, and Rieser replied, “As for getting this [letter] to Obama, can you think of any current senators who have been particularly outspoken about nuclear arms control? I am not sure myself, but can easily find out. If one exists, he/she could find a way to get it to Obama. Otherwise, I have ways of doing it.”

Rieser did indeed have ways of making things happen. After more than three decades of working for Senator Leahy, Rieser had a reputation for taking on the toughest, most politically risky issues and convincing powerful politicians to do the right thing. He was relentless. In 1992, over the objections of the Pentagon, he had played a key role, as Senator Leahy’s aide, in getting Congress to support legislation to ban the export of land mines. He also found a way to enable Leahy to obtain hundreds of millions of dollars to help Vietnam clear unexploded munitions left behind by American forces and to address the ongoing effects of Agent Orange, as well as to open the door for the U.S. to restore diplomatic relations with Cuba.

At the time, I was unaware of the true scope of Rieser’s influence as a key aide on the Senate Appropriations Committee. And neither was I aware that he had a personal interest in the Oppenheimer case. But I learned that his father, Dr. Leonard Rieser, had worked at Los Alamos as a young physicist, in 1945, and, like other scientists, had revered Oppenheimer. As a child, Tim Rieser grew up hearing his parents talk about the Manhattan Project and Los Alamos, where his mother ran the nursery school. For him, the injustice that had been inflicted on Oppenheimer was also personal.

Later in the summer of 2016, Rieser persuaded Senator Leahy and three other Democratic senators—Martin Heinrich; Edward J. Markey, of Massachusetts; and Jeff Merkley, of Oregon—to sign a letter to President Obama urging nullification. The letter was sent on September 23, 2016. We knew the clock was running out on the Obama Administration. But we still hoped that the appeal of four senators could persuade the President to issue an executive order. Heinrich and another senator, Tom Udall, of New Mexico, had a meeting with Secretary Moniz in early July, 2016—but it went badly. Instead, Moniz said that the Department of Energy would create a student fellowship in Oppenheimer’s name. He thought that this was a concession. We thought that it was nothing.

Things were not looking good. Senator Heinrich said that he had repeatedly talked to Moniz but the Energy Secretary was not moving from his position. Marty and I still hoped that Obama could be persuaded to issue an executive order as he left the White House, in early 2017. But nothing happened. And then Donald Trump won the November election. With Trump in the White House, Marty and I gave up.

Nothing happened on the Oppenheimer case for the next four years. Marty and I thought that it was hopeless. In June, 2017, I happened to run into Ernest Moniz at the memorial service for the former national-security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski. I asked him why he had refused to nullify the ’54 decision—and he unapologetically insisted, “My legal counsel said it was not possible.” We argued briefly, and I walked away feeling dejected.

But when Biden won back the White House, in 2020, Rieser revived the project. On June 16, 2021, the same four senators who had sent the 2016 letter signed a similar one to President Biden. A couple of months later, after hearing nothing in response, Rieser called a friend who had recently been appointed Assistant Secretary for Congressional and Intergovernmental Affairs at the Department of Energy. They knew each other only because, some years earlier, Rieser had bought a Ping-Pong table from him that had been advertised on Craigslist. Rieser asked his friend about the status of the letter to President Biden. The Assistant Secretary looked into the matter and told Rieser that the answer was likely going to be negative. That would close the door firmly shut. Rieser responded, “Then don’t answer it. I’m going to draft a different letter.”

Rieser decided that it was time to back off the White House and to instead appeal to the newly installed Energy Secretary, Jennifer Granholm. So he went back to his office and substantially revised the original letter signed by the four senators in 2016. The new version, though it called on the Secretary to vacate the 1954 A.E.C. decision, also made clear that, by doing so, she would not be reinstating Oppenheimer’s security clearance. That would require a whole new security review, which was obviously not possible, since Oppenheimer had died long ago. Rieser then began reaching out to Senate staff, and Senator Leahy spoke directly to his Senate colleagues, recruiting new signatories for the letter addressed to Granholm. This process took more than a year, but by the spring of 2022 they had forty-three Senate signatures, including four Republicans.

That was a formidable achievement. But Rieser was still worried that this would not be enough political capital. He expanded his campaign by reaching out to the director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, Thom Mason, a fifty-seven-year-old physicist. Mason said that he was sympathetic, but skeptical of nullifying the 1954 decision if that meant restoring Oppenheimer’s security clearance. He felt that what was needed was a formal apology for the wrong that had been done to Oppenheimer, and said that he would write his own letter to the Energy Secretary.

By happenstance, I was visiting Los Alamos in March of 2022. Christopher Nolan, the director of the forthcoming film “Oppenheimer,” had invited me to visit the set. Nolan had written the script based on “American Prometheus.” Not surprisingly, the film spotlights the Oppenheimer trial.

Knowing of my presence in Los Alamos, Rieser contacted Mason and asked if he would see me. A meeting was arranged, followed by dinner. Mason and I had an entirely civil debate about the merits of nullification versus an official “apology” for what had been done to Oppenheimer. I argued that an apology was not sufficient and that nullification was required precisely to restore the integrity of the security-review system. Mason came around to this argument once he was persuaded that “nullification” would not restore Oppenheimer’s security clearance. He not only agreed to rewrite his letter—he then obtained the signatures of the eight surviving former directors of the Los Alamos lab.

Mason’s intervention was extraordinary. Here was the director of a science-and-weapons lab, the man ultimately responsible for managing thousands of scientists on classified projects, urging nullification of the 1954 Oppenheimer verdict.

Rieser then contacted Mason’s counterpart at the Idaho National Laboratory, John Wagner, who also agreed to send a letter. Rieser then obtained additional letters of support from the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (his late father had been chairman of the board), the Federation of American Scientists, the American Physical Society, and others. A letter was also signed by three historians: the Pulitzer Prize winner Richard Rhodes (“The Making of the Atomic Bomb”), Robert Norris (the biographer of General Leslie R. Groves), and myself. The J. Robert Oppenheimer Memorial Committee weighed in, and the Los Alamos County Council adopted a resolution urging nullification.

In retrospect, this was the turning point. In September, 2022, Rieser bicycled down to the Department of Energy and hand-delivered a binder with all the correspondence and supporting materials. Secretary Granholm and her staff read it all, and they conducted their own review of the historical record. She also took the time to read “American Prometheus.”

Tragically, Marty Sherwin had succumbed to lung cancer in October, 2021, at the age of eighty-four. Rieser and I thought that we had done everything possible to lay the groundwork for a nullification decision. But we were painfully aware that the ethos of the national-security bureaucracy stood in our way. There were still those in the Energy Department who argued that vacating the decision against Oppenheimer could appear to create a double standard on behalf of politically powerful individuals.

Granholm concluded otherwise. She reasoned that vacating the A.E.C. decision was not only necessary to correct a grave injustice but was also important to the integrity of the security-review process. At the end of her six-page memo justifying her decision, she wrote, “When Dr. Oppenheimer died in 1967, Senator J. William Fulbright took to the Senate floor and said, ‘Let us remember not only what his special genius did for us; let us remember what we did to him.’ ”

Granholm’s decision is a stunning reversal. It took tireless persistence and a measure of serendipitous good luck. It corrects the historical record. It is important not just for students who will now be able to read the last chapter and learn that what was done to Oppenheimer in that kangaroo-court proceeding was not the last word. He was a brilliant scientist, a loyal American, and the victim of a gross miscarriage of justice.

This lesson is particularly important because of Oppenheimer’s status as a scientist. We are a society immersed in science and technology based on some of the very physics that Oppenheimer and his colleagues pioneered. And yet many in this country still distrust science and scientists. Just look at the way that scientific facts were distorted and ignored during the pandemic. Look at the vilification of Dr. Anthony Fauci and other public-health experts.

In some discernible measure, we can blame the legacy of the flawed Oppenheimer security trial for this distrust. In 1954, America’s most celebrated scientist was falsely accused and publicly humiliated, sending a warning to all scientists not to engage in the political arena as public intellectuals. This was the real tragedy of the Oppenheimer case. What happened to him damaged our ability as a society to debate honestly about scientific theory—the very foundation of our modern world. Granholm’s courageous decision has reaffirmed not only that the federal government is capable of correcting its mistakes but that government employees, regardless of their stature, can express opinions that challenge the conventional wisdom without fear that they will be falsely branded as disloyal. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com