Once upon a time in a land not so far away, America produced men and women with the ability to evade category. No one quite knew how to classify Walt Whitman’s poetry when America’s bard made his debut in 1855, not even Ralph Waldo Emerson, who called Leaves of Grass “American to the bone.” When Elvis Presley first hit the airwaves in 1954 with his gas pedal cover of “That’s Alright,” white listeners thought he was black, black listeners knew that he wasn’t, but neither knew quite what to call it. Blues? Not really. Country? Definitely not. Rock and roll? What is that?

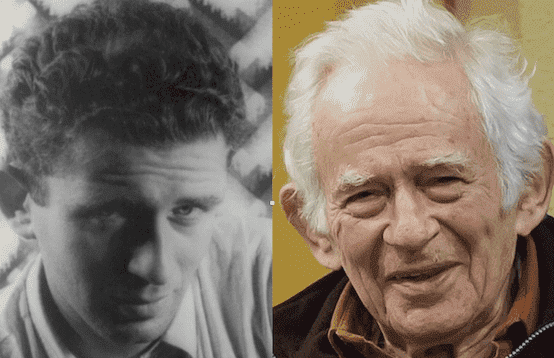

Among the gloriously unclassifiable was the novelist Norman Mailer, who cautioned readers to avoid “playing the Tuesday morning music on Saturday night.” Full of music and multitudes, Mailer wrote in the individualist tradition of not adhering to any particular genre or style. He was a novelist of wildly different types—war epics, historical fiction about the CIA and Ancient Egypt, murder mysteries, experimental writing. He was one of the creators of literary journalism, a polemicist, essayist, and biographer. A winner of two Pulitzer Prizes and one National Book Award, he was also one of the great writers of the 20th century.

His politics were equally difficult to place and offer a demoralizing contrast to the contemporary era of excessive labeling. Never boring or predictable, Mailer presented challenging surprises to his audience. He claimed his literary ambition was to fuse the ideas of Marx and Freud into a project that would “cause a revolution of consciousness” in the American public, but he was no ideological box-checking leftist. In fact, he was an opponent of feminism (some of his concerns become increasingly relevant and insightful, while others have aged quite poorly), a warrior against political correctness, an advocate of religious belief, and a proponent of small-scale communities and economies.

To frustrate and flummox his admirers and critics, when interviewers would ask him to define his politics, he used a term of his own invention: “left-conservative.”

Mailer’s leftism was easy to identify: he despised corporate power and its influence on American culture, he hoped to subvert most traditions that governed American life, and, from John F. Kennedy to John Kerry, he uniformly supported Democrats in national elections. The conservative aspect is more subtle and interesting. Hayek would have appreciated it, because it was Mailer’s own avoidance of the “fatal conceit”—the belief, as Hayek described it, that human beings can predict, solve, and troubleshoot every communal problem, large and small.

As much an affirmation of the complexity that is often missing from contemporary debate, Mailer’s left-conservatism serves as a warning against the vices and excesses of today’s left-of-center agitators and activists. In an interview with fellow novelist Martin Amis, Mailer explained:

Liberalism worries me. It strikes me as a cover story for people who are essentially totalitarian. They want it their way. They often have one point—a single-minded agenda—and they tend to exclude all the other possibilities. The best thing that can be said for conservatism, and there are a great many terrible things to say about it, but the best thing to say about it is that they (conservatives) do tend to have a certain appreciation of the world as a whole. I become uneasy when I find people drawing up solutions, which is, of course, the great vice of the left, to solve difficult problems, because I think they cut out too many of the nuances. So, “left-conservatism” is my way of reminding myself that you have to deal with everything in context. A solution that works in one place doesn’t work in another.

In an interview with The American Conservative, Mailer admitted that “left-conservatism” is an oxymoron, and as such he has to “redefine the term every day.” For Mailer, the “remains of left-wing philosophy” worth preserving are those that caution against excessive wealth inequality: “The idea that a very rich man should not make 4,000 times as much in a year as a poor man,” as he put it.

In his novel about Jesus Christ, The Gospel According to the Son, Mailer emphasizes the Christian Messiah’s instruction against the pursuit of wealth and concerns for the souls of the rich. He was not an adherent of any organized religion, but the idea that religion has value in society appealed to Mailer, and further separated him from many of his friends and associates on the left. He also excoriated those he called “flag conservatives”—a term that currently resounds, as it indicts people who care more about nationalistic power than conservatism’s dependable values.

“Liberalism depends all too much on having an optimistic view of human nature,” Mailer told TAC, “But the history of the 20th century has not exactly fortified that notion. Moreover, liberalism also depends too much upon reason rather than any appreciation of mystery.”

A practitioner of the literary arts and a self-described “amateur philosopher,” Mailer, in an expression of conservatism, admitted that it is uncertain how his ideas would move from pathos to the pavement. “We do not really know what works in a modern society,” Mailer said, but he did offer his own idiosyncratic hypothesis when he ran for mayor of New York in 1969. Pollution of the air and noise varieties, a vanquishing of the spirit of citizens, the burial of the genius of the poor, and an emptying of lives into drug addiction are the problems Mailer hoped to address with his mayoral campaign, which featured the delightful slogan “Throw the Rascals In!”

“The face of the solution may reside in the notion,” Mailer wrote in an essay making his pitch to voters, “that the Left has been absolutely right on the critical problems of our time, and the conservatives have been altogether correct about one enormous matter—which is that the federal government has no business whatever in local affairs.”

He continued to juxtapose the New York of his youth with the barely recognizable city of his adulthood: “The style of New York life has shifted since the Second World War from a scene of local neighborhoods and personalities to a large dull impersonal style of life which deadens us with its architecture, its highways, its abstract welfare, and its bureaucratic reflex to look for government solutions which come into the city from without.”

Mailer’s plan of restoration was less a large-scale solution than the creation of a system that would have allowed for small-scale experimentation. He advocated that New York become an independent city-state, and that each borough have autonomy to dictate its own policies, rules, and regulations. “Power to the neighborhoods!” Mailer would often declare during his reportedly rollicking speeches.

Left-conservatism gains coherence if one understands it as an overall disposition instead of a systemized set of beliefs. It is an attempt to assimilate leftist critique of society, along with many of the political positions that logically follow, into an overarching conservative awareness and attitude. Norman Mailer’s construct of it, which enjoys a kinship with the writing of Christopher Lasch, might or might not allow for the alleviation of the varying sociopolitical crises that are currently manifest in American life, but it would lead to essential psychic improvements in the lives of many.

Left-conservatism offers valuable instruction for much of the right wing, especially “flag conservatives” who seem stupefied as to why young Americans with debilitating student debt, unreliable health insurance, and high housing costs feel resentful of capitalism. It would also introduce a little sanity and perspective into the thought patterns of leftists who boast of their desire to “burn it all down,” condemn anyone who expresses an opinion slightly dissenting from their totalizing ideology, and seek to transform every institution—especially those of higher learning—according to their latest designs.

Many social critics and commentators have made the obvious point that Americans have become increasingly emotional, prioritizing feelings over facts and all other intellectual and rational means of evaluation. But for all the contemporary emoting and shrieking, there is something cold and programmatic about present-day debate. It seems to have banished the imagination in its insistence that everyone recite lines from ideological scripts authored in committee by their respective political tribes.

In his magnificent book on the Apollo 11 space mission Of a Fire on The Moon, Mailer writes, “It could be said that the psychology of machines begins where humans are more machinelike in their actions than the machines they employ.” Left-conservatism is beautifully human because it is full of creative contradiction. Americans now obsessed with machine-like consistency from their writers and leaders would do well to remember what Ralph Waldo Emerson had to say for that particular vice in disguise as virtue. He called it “the hobgoblin of little minds.”

David Masciotra (www.davidmasciotra.com) is the author of Mellencamp: American Troubadour (University Press of Kentucky), Barack Obama: Invisible Man (Eyewear Publishing), and the forthcoming Half-Lights at Evening: Essays on Hope (Agate Publishing).

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com