In the late nineties, I had in my possession a copy of the photographer Nan Goldin’s monograph, “I’ll Be Your Mirror,” which was published in concordance with her 1996 Whitney Museum mid-career survey of the same name. I no longer have the book (I parted from it along with the old boyfriend to whom it actually belonged), but I can still vividly recall most of the photographs in its pages. The pictures, which portrayed the life of Goldin, her friends, and her lovers in various bohemian, gender-bending, hard-partying enclaves in the latter decades of the twentieth century, were taken in a kind of snapshot, off-the-cuff style, not especially concerned with either conventional composition or reportorial detachment. They were, instead, unvarnished and sensual, documenting “the random gestures and colors of the universe of sex and dreams, longing and breakups,” as my colleague Hilton Als wrote in a 2016 profile of Goldin, for this magazine. As a relatively sheltered twenty-one-year-old living, at the time, in Tel Aviv, I viewed the photographs as louche cosmopolitan missives from another world, one that seemed terrifying and glamorous almost beyond belief. The catalogue’s front cover featured a self-portrait: a shot of Goldin’s face in profile, looking out a train window, her gaze sombre and unblinking. What did she see?

What Goldin has seen—and the power of her vision—is explored with great skill and care in “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed,” Laura Poitras’s excellent, wrenching documentary about the now sixty-nine-year-old photographer. Poitras’s aim in the film is twofold. First, she sets out to tell the story of Goldin’s life, from her oppressive childhood in a loveless Jewish family, riven by her older sister’s traumatic suicide, through her early years taking pictures, when, through tumults of both joy and suffering, she matured as an artist, toward her ascent as one of the most important photographers of her generation. This thread, which is helped along by Goldin’s own sardonic, gravelly voice-over, is interspersed with the second strand that Poitras pursues, which involves the photographer’s 2017 establishment of the activist group P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) in response to the opioid crisis.

Following an operation in 2014, Goldin was prescribed the opioid OxyContin as a painkiller. Although she took it as directed, she “got addicted overnight,” she wrote, in the January, 2018, issue of Artforum, in what amounted to P.A.I.N.’s founding manifesto. Her life quickly turned into one that “revolved entirely around getting and using Oxy.” When she managed, barely, to pull out of the vortex of addiction, three years later, she realized that “the Sackler family, whose name I knew from museums and galleries, were responsible for the epidemic.” As my colleague Patrick Radden Keefe has reported in this magazine (he is also interviewed in the documentary), the Sacklers were aware of the considerable risks of OxyContin, a medication that they formulated and sold under the auspices of their company, Purdue Pharma, enriching themselves and kick-starting an avalanche of addiction and death. (In the United States alone, the death toll of opioid overdoses is in the hundreds of thousands.) For many years, the Sackler name was plastered on various cultural institutions to which the family had donated money. Goldin, whose work is held in the permanent collections of many major museums, decided to use her art-world standing to target the Sacklers; through demonstrations in various museums, such as the Met, the Louvre, and the Guggenheim, she shamed the Sacklers and the institutions that were willing to take the family’s blood money—funds which, P.A.I.N. argued, the Sacklers should use to redress the damage wrought by the opioid crisis.

“All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” opens with footage from the first direct action that P.A.I.N. took, in March of 2018, beside the Temple of Dendur in the Met’s Sackler Wing—possibly the crown jewel of the Sacklers’ philanthropy. “I’m really nervous,” Goldin mutters. Dressed in black, with her curly ginger hair pulled back and her lips slicked in red, she huddles with fellow-activists before breaking into a full-throated mike check. “A hundred thousand dead!” she shouts, and the group echoes her. “Temple of money, temple of greed!” they then yell. “Sacklers lie, people die!” While this call-and-response goes on, the activists toss prop pill bottles (labelled with the words “OxyContin: prescribed to you by the Sackler family, major donors of the Met)” into the temple’s reflecting pool, before lying on the museum floor: a die-in.

Serving as a conscious model for P.A.I.N. was ACT UP—the activist group established, in 1987, to protest, through civil disobedience and direct action, the neglectful and bigoted government response to the AIDS epidemic. As I watched, I kept thinking of the well-known words featured on the back of a leather jacket worn by the late artist, writer, and ACT UP figure David Wojnarowicz, Goldin’s friend: “If I die of AIDS—forget burial—just drop my body on the steps of the F.D.A.” This suggestion of unearthing what is typically hidden in order to force the world to confront the truth is a clear ethical imperative for Goldin, who is as interested in beauty as she is in representational honesty.

There is perhaps no one better suited to tell Goldin’s story than Poitras, an Oscar-winning filmmaker best known for “Citizenfour,” her documentary on Edward Snowden, and “My Country, My Country,” a film about the U.S. occupation of Iraq. (The filmmaker has her own activist bent; after the release of “My Country, My Country,” she found herself on a federal watch list.) In “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed,” Poitras seamlessly weaves together Goldin’s political work and her photography by drawing implicit parallels between the two—something that Goldin herself has done. “I decided to make the private public by calling [the Sacklers] to task,” Goldin wrote in Artforum, a decision she enacts, first of all, by publishing, alongside her call to arms, some of her photos from earlier in the decade. These pictures include images of Sackler plaques that Goldin photographed in various august art institutions, but they also depict her descent into OxyContin hell. In “Crushing Oxy on My Bed, Berlin, 2015,” we see a well-worn pill organizer on an unclean duvet, and a platter with residues of drug powder on it. This is not a pretty moment, but for Goldin it must be seen.

Throughout her childhood, Goldin was encouraged to stay quiet. Growing up in early-nineteen-sixties Maryland, she was aware of the constant tension in her home. “Don’t let the neighbors know,” her mother would often say to her. (These attempts at hiding, Goldin says in voice-over, didn’t help; the neighbors could hear the family fighting.) The strife focussed on Goldin’s older sister, Barbara, an intelligent, spirited girl, given to fits of anger and acting out sexually. Barbara, with whom Goldin was very close, refused to conform to the conventional strictures her parents tried to impose on her, and the elder Goldins institutionalized her again and again, silencing her “by calling her mentally ill,” Goldin says. In 1965, Barbara killed herself by lying on train tracks. “The police came into the house,” Goldin recounts. “My father started wailing on the front lawn. . . . And I heard my mother say, ‘Tell the children it was an accident.’ My interpretation from that minute was: denial. She didn’t want us to know the truth. That’s when it clicked.”

After her sister’s death, Goldin was shuttled between foster homes, until, in her mid-teens, she ended up at a progressive school in Boston where she was given her first camera. Deeply shy, Goldin found power and protection in photography. The wail was no longer stifled, but channelled. (Taking pictures, she says, “gave me a voice.”) After school, Goldin moved to Cambridge, where she lived with a community of drag queens, her first main subjects. “I wanted the queens to be on the cover of Vogue,” she says, her words sounding over intimate images of her sinuous, beautiful cohort. At the time, however, even just survival was an art for this community. “My roommates were running away from America, and they found each other,” she says. “It was about living out what they needed to live out, in spite of the reaction from the outside world.”

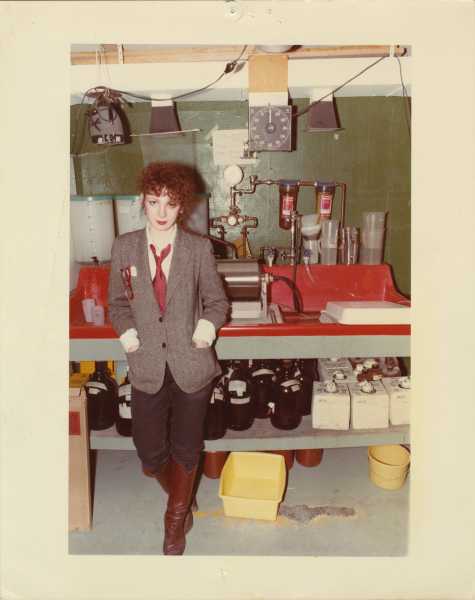

Nan Goldin standing in a darkroom.Photograph by Russel Hart Courtesy of Nan Goldin

This aligning with the marginal and the oppositional became a mainstay of Goldin’s life and photography. She moved to downtown New York in the late seventies, to a “shithole loft” on the Bowery (“There was no light. . . . We used to fuck in the elevator. There was a lot of drugs. Always a lot of drugs. A lot of coke, a lot of speed.”), and her aesthetic as a photographer crystallized. Many of her pictures featured her close friends: the photographer David Armstrong, the actor and writer Cookie Mueller, the sculptor Greer Lankton. In “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency,” her best-known series, which she began presenting live in the early eighties in the form of an ever-changing slide show set to a shifting soundtrack, Goldin took the role of participant observer, capturing private, close-to-the-bone moments—of sex, of violence, of elation, of addiction, of heartbreak—whose liveliness and vibrancy stemmed from their depiction of the fleeting and fatalistic, Eros intertwined with Thanatos.

One of the cores of “The Ballad” is Goldin’s stormy, years-long relationship with a man named Brian. The series depicts the couple’s happier moments—fucking, cuddling, hanging out; it portrays, too, the darker sides of the relationship, which ended after Brian assaulted Goldin in a fit of rage and jealousy, nearly blinding her. (In the self-portrait “Nan One Month After Being Battered,” from 1984, Goldin stares at the camera, her face opaque and masklike, a bright slash of crimson lipstick echoing the hue of her badly bruised eye sockets.) Both Goldin and her lover were heroin users, and images of drug-taking in her work, too, range from the casually jaunty (in “Getting high, New York City,” from 1979, a man cooking heroin ties off with what appears to be a bright-red belt, whose poppish color matches that of a rotary phone at his feet), to, later, “Nan at her bottom…, The Bowery, NYC,” from 1988, in which a different red phone appears, this time held by a bloated Goldin, sitting on her dishevelled bed, clearly in the grip of addiction. The energetic, party-like mess of the earlier photo—a sparkly high-heeled pump is flung to one side of the image—is replaced with the murkier squalor of the committed junkie.

Goldin went to rehab in 1988. By then, her position as art star was established, and there was no longer much of the critical and commercial resistance that her work had initially met with (which she sums up, in the film, by mimicking her naysayers: “This isn’t photography! Nobody photographs their own life!”). But her devotion to showing her own reality, as she saw it, continued. Poitras’s film includes a snatch of promotional advertising from Purdue Pharma, which the company originally released to reassure patients that opioids, which they had long been taught to fear as addictive, were in fact safe to use in the form of OxyContin. “Don’t be afraid to take what they give you,” a man says to the camera. Considering the catastrophic results of this falsity, I found the scene chilling to watch, but the words also struck me in another way. Taken symbolically, they made up the exact credo that Goldin, throughout her life and career, and long before her activism in P.A.I.N., seems to have intuitively refused. Her entire path, in fact, has been based on being afraid to take what “they” give you. Instead, she has lived her life—and made her art—according to her own terms. The animating trauma of her life, her sister’s silencing and suicide, was “about conformity and denial,” she says. “My sister was a victim of all that, but she knew how to fight back. Her rebellion was the starting point for my own. She showed me the way.”

In its five years of activism, P.A.I.N. has made immense and unanticipated strides. Thanks to the group’s pressure, the Met, the Guggenheim, and the National Gallery in London, among other major art institutions, have cut ties with the Sacklers, and have taken the family’s name off their halls. (P.A.I.N., meanwhile, has since moved its focus to harm-reduction efforts.) And yet, the effects of the Sacklers’ greed and mendacity cannot be walked back, and Purdue Pharma’s declaration of bankruptcy has granted the family civil immunity, leaving it off the hook and still enormously rich.

Toward the end of the documentary, Goldin and some of her fellow-activists sit in on a Zoom call of a legal proceeding, in which, as one of the requirements of the bankruptcy filing, members of the Sackler family, including Richard Sackler, the former president of Purdue Pharma, are made to view the testimonies of OxyContin victims. “I believe Richard said that he is listening. I believe he is also supposed to say that he is watching the video. . . . Can he confirm that?” a lawyer on the call asks. “I can confirm that I saw. . . . I’ve seen everything,” Sackler responds. As she watches the Zoom, a burning cigarette in her hand, Goldin’s face twists in a bitter smile. For her, unlike for Sackler, seeing everything has real meaning. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com