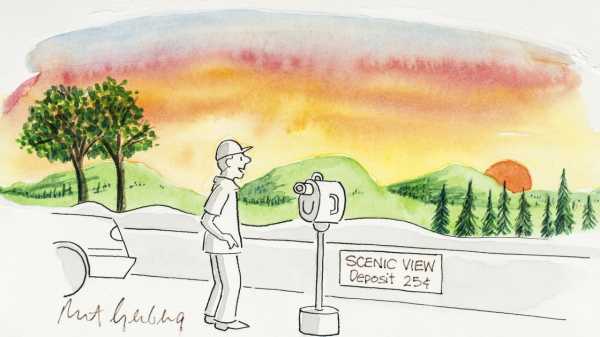

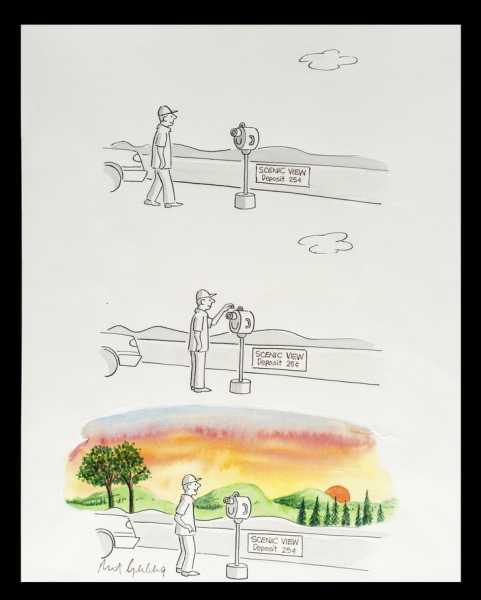

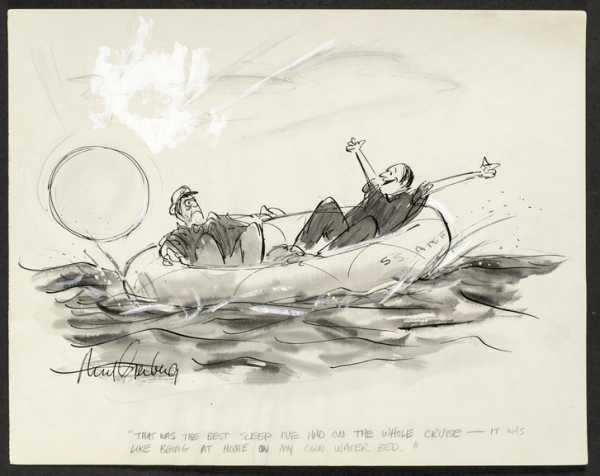

Mort Gerberg, a star pitcher of The New Yorker’s softball team and a contributor to the magazine since 1965, is the subject of a New York Historical Society retrospective.

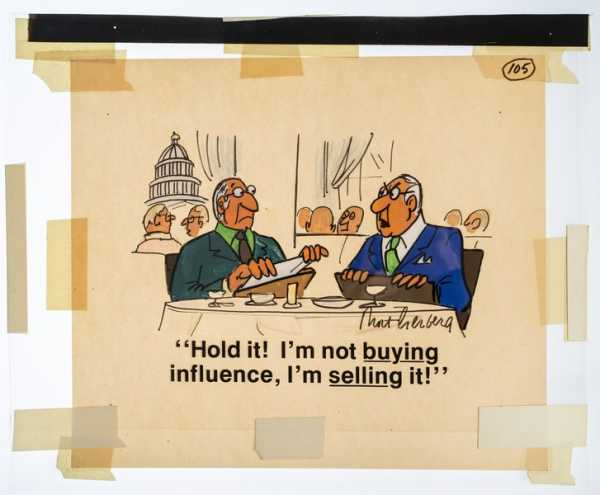

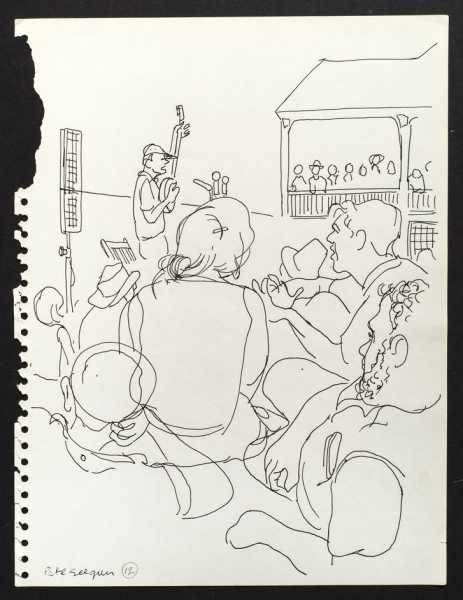

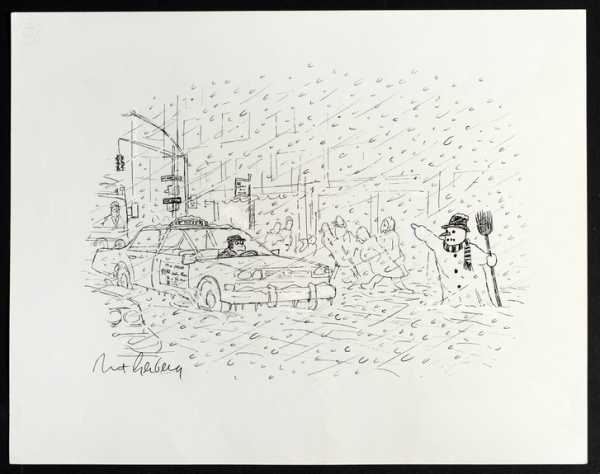

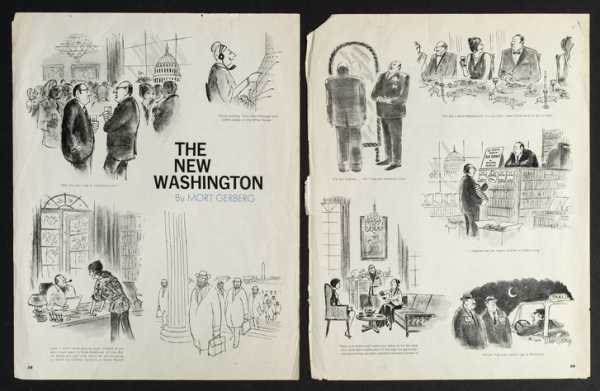

Illustrations by Mort Gerberg

Mort Gerberg, a star pitcher of The New Yorker’s softball team and a contributor to the magazine since 1965, is the subject of a New York Historical Society retrospective, “Mort Gerberg Cartoons: A New Yorker’s Perspective,” which opened this month. In conjunction with the exhibition, Fantagraphics Underground will be publishing a new collection of Gerberg’s work, “Mort Gerberg on the Scene: A 50-Year Cartoon Chronicle.” All in all, it seemed like a good time to check in with Mort (the Fort) Gerberg, as he’s known on the mound.

You’ve often told me that a cartoonist is like an oyster. Can you explain that simile?

You think of an oyster: he swims around in the ocean and that’s his world. He’s just, da da da da da, doing oyster stuff. And every once in a while, or maybe more frequently than most, a piece of schmutz, like sand, gets inside, underneath the oyster’s shell. And, when the oyster gets that sand inside him, he gets irritated by it. And so the oyster’s automatic, natural reaction is to make a pearl. In a similar way, I think the cartoonist—he’s a person who goes through the world and, more often than other people, gets irritated, or annoyed, or at least he notices something that’s schmutz-ing him a little bit, or bothering him. And, naturally, he reacts to it. And what cartoonists then do is react and produce a pearl—ha ha—of wisdom.

And when did you first exhibit your oyster tendencies?

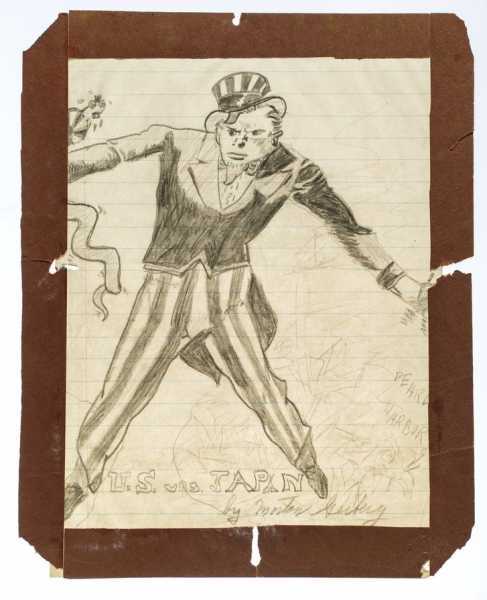

I look at some of the early, early work—in the exhibition there’s a drawing that I did maybe when I was eight years old, with Uncle Sam beating up some bad guy, Kojo the snake, I think it was. So that was 1941, ’42, and it must have been a reaction to the United States being bothered by the bad guys. I grew up small, skinny, undersized, younger than everybody, wearing glasses, and I had no retaliation for getting beaten up by the bad guys in the neighborhood, except maybe drawing. I guess, channelling all those hurts and grievances, it just came out that way. A lot of my early drawings that I sold to The New Yorker had all that stuff—being aware of injustices, let’s say.

And what things have been irritating you more recently?

Well, obviously the more recent ones have to do with the political environment, which is so utterly wrong. That’s what feeds many new cartoons, the whole spectrum of wrongs that I feel are going on in the world. There’s plenty of material on that score.

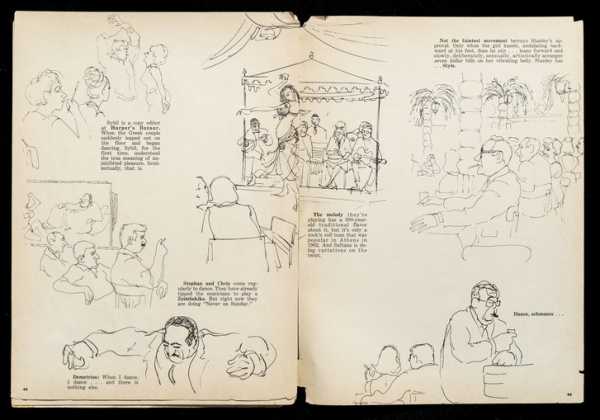

The show encompasses not just your single-panel gag work for The New Yorker, but reportage, syndicated strips, drawings for short animations. How and why did you develop such a diverse practice?

I think there were two main reasons. One was to produce an income. And secondly was because I was following some natural interests. In regard to the first part, when I started doing cartoons, which I guess technically was in the early sixties, and I was working my way up, the smaller magazines that were first available to me were paying maybe five, ten, twenty-five dollars. That meant I had to do a lot of drawings, make a lot of sales. Then, gradually, I worked my way up the ladder—Saturday Evening Review, Saturday Post, Look magazine, Esquire, then I sold to Playboy, and then, finally, a few years later, started to sell to The New Yorker. But still, and I think this is true for all cartoonists, it was just not possible to make a really decent living by selling to one or two magazines, even if you’re selling to The New Yorker. You needed something else.

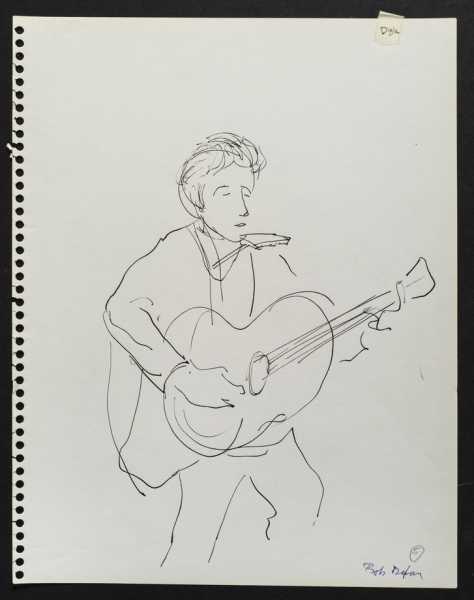

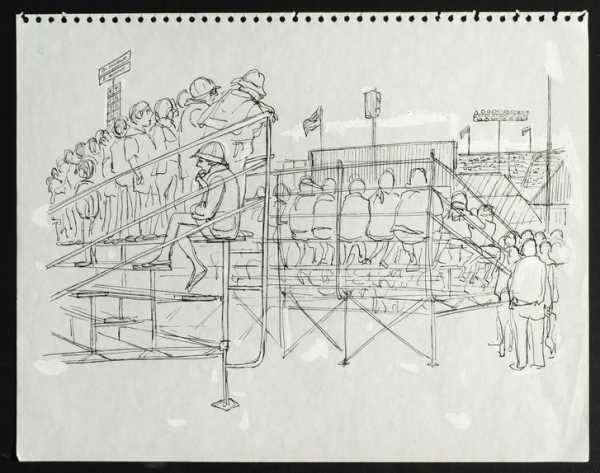

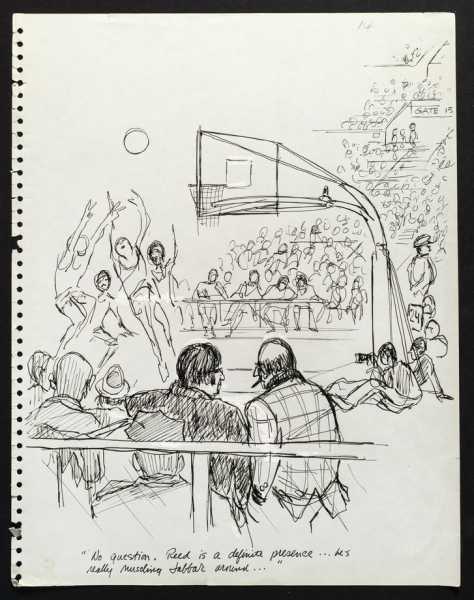

So you looked to do other things. First of all, multi-panel spreads or multi-page spreads, I would go to a magazine and I would say, “Suppose I do you something on the World’s Fair,” and I would do two pages of cartoons. And then that led to going sketching, which I loved to do, and that turned into doing reportage. I would go to a magazine and say, “I’ll give you four pages of sketches of the Newport Folk Festival.” It was my interest in these things, covering a wide range—political, social happenings around me that were, yes, irritating me, or at least getting my attention, or it was something like sports. I did stuff on baseball and tennis, I even went out and covered karate championships.

Did you pick up any moves?

No! But it was something that interested me. So it was doing a variety of things I hadn’t done before and even making up things, like the feature I started doing in the seventies, “Cartoon Views of the News,” on Channel 4, where I said, “I’m now going to draw a cartoon and talk to you while I draw, all within one minute and twenty-nine seconds.” This is my famous thing. I’m going to jump off a podium of three hundred feet into a wet sponge without breaking my neck.

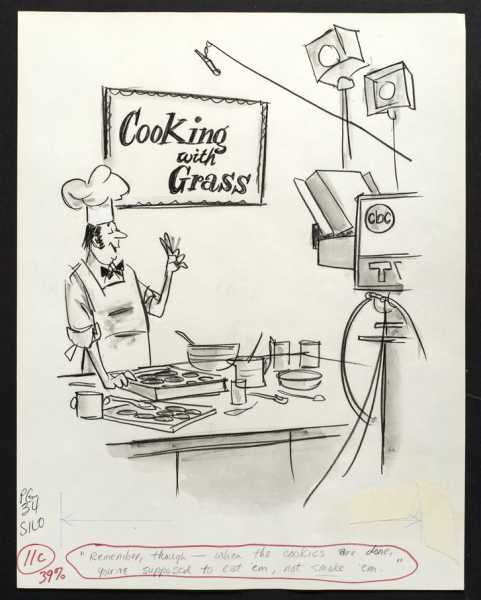

Some of your cartoons and comics that seemed so rooted in the time in which you drew them feel suddenly relevant again. I’m thinking about your women’s-rights and marijuana-legalization cartoons from the sixties and seventies in particular. Is that a thing that struck you when you were putting this show together?

Absolutely. I was surprised at a lot of things when I started looking at the quote-unquote older stuff. I was amazed that I was doing marijuana cartoons so early and even more that they were being published by the Saturday Evening Post, the most middle-America magazine. And then with the marijuana-legalization resurgence, it seemed like a replay of a book that I did called “High Society.” I went to something that Gloria Steinem was doing recently and said, “This is the same story! The same marches as the series of cartoons I did on women’s rights, the book ‘Right On, Sister.’ ” And then, of course, with the current President who shall remain unnamed, it seemed like the same kind of social and political irreverences were being committed as in the Reagan years, when I published my book “Reaganworld.” The more things change, the more they stay the same, right? It sounds better in French.

One of your great subjects is music and musicians. You yourself play the piano, and we’ve chatted before about how many cartoonists are musical. What do you think explains that correlation?

One of the great cartoonists is Lee Lorenz, the former New Yorker cartoon editor—he’s just fabulous. But Lee is also one of the great jazz-cornet players. And he plays down at Arthur’s, in the Village. So my wife and I went down one Sunday night, and then that Tuesday—I come into The New Yorker with my weekly batch of cartoons, and Lee is saying, “Oh, it’s so great you two came down to hear me play, that was so nice of you.” And I said, “Lee, are you joking? I just love it. I usually play by myself, but I wish I could play with a group and maybe get gigs and actually play clubs and make some money, like you do.” And Lee said, “Yes, and then you’d have two careers that you couldn’t make a living from.”

But I do think there is a correlation between music and art, and I think the distillation for me is that it’s knowing instinctively when to come in, and when to go out. Because, in a cartoon, in a single-panel anyway, it’s all a question of timing, and if you have a good sense of timing and rhythm it’s really improvisation. I mean, I can sit at the piano and kind of fool around and play a tune and suddenly something has happened and I think, I’ve done something that I don’t think I’ve done before, and I think, Where did that come from? And, very often, when you sit and do cartoons, you think, Where did that come from? And I think it’s letting the right brain really take over.

Even when you started doing this crazy thing that is cartooning, fifty-some years ago, people were telling you it was a dying trade. What compels you to keep at it?

Well, it’s always been on the outs. They told me it was on the outs when I first started, in 1962. But what makes me do it, and probably all the ones who stay with it all their lives, is simply that they have no choice about it. Cartooning is not anything that you choose to do. Cartooning chooses you. Kids pick up chalk or pencils and papers, and they start to draw. And the only thing that’s different is that cartoonists keep drawing. They couldn’t stop drawing.

In point of fact, I had been told, growing up, being the first born of the firstborn of the firstborn, that I should be a doctor or a lawyer or something reasonable. When my uncle said, “Well, what do you want to do when you grow up?,” I said,” I want to draw,” and he said, “No, you can’t do that: being a cartoonist is no job for a Jewish boy—it’s no job for any boy.” So I was told to go to school and maybe go study advertising, and get a job. And I did that for about eight or nine years, and I was so unhappy doing it.

At a New Yorker holiday party, years ago, I said to Charles Addams, “I gotta ask you the same thing, Charlie, that everybody asks. Where do you get ideas from and why do you do this?” And he looked down and he said, “Well, Mort, I’ll tell ya, I don’t really know. I’m like a cow, I just give milk.” That was his answer.

We’ve got cows—we’ve got oysters.

It’s a whole menagerie.

Sourse: newyorker.com