For more of our year-end literary coverage, read James Wood on four books that deserved more attention; Katy Waldman on her favorite books of the year; and Kathryn Schulz on the best facts she learned from books in 2018.

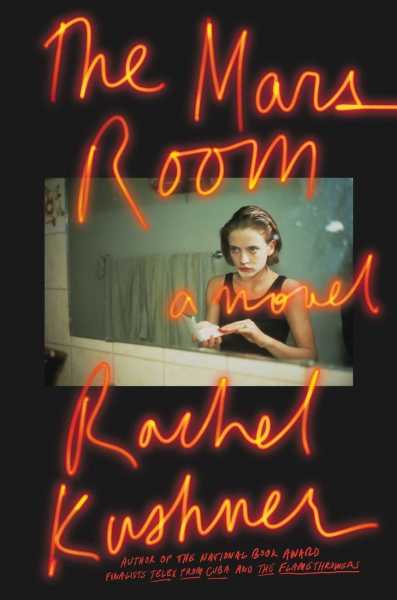

“The Mars Room,” by Rachel Kushner

I recommended Rachel Kushner’s novel “The Mars Room” midway through the year; now I’m shamelessly back to give it the full pine-scented December endorsement. Don’t let the setting—a maximum-security women’s prison in California—scare you off. Kushner is clear-eyed about the habitual brutalities of our carceral system, but she has no interest in preaching about them. I don’t even think she’d know how. She’s too weird and free. This is a novel about people, and the stories they tell to remember the worlds they used to know, and to try to survive the one they’re stuck in now; Kushner’s style can seem almost dictated, as if her characters simply stepped up to her and started talking. When I read the novel, in May, I admired its tough, salty humor and quirky narrative risks. (Did I mention that Kushner quotes the Unabomber’s diaries at length, and that it totally works?) But there’s a hot heart pumping beneath all the coolness. In June, when the family-separation crisis at the border became national news, I thought of Romy Hall, the novel’s protagonist, whose young son has been taken from her and placed God knows where, and I have been thinking of Kushner’s evocation of her grief, love, and wild hope ever since.—Alexandra Schwartz

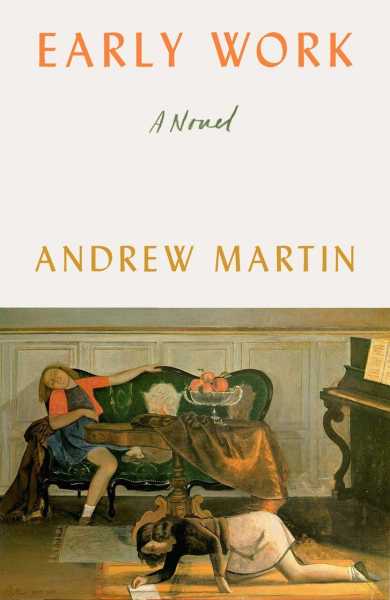

“Early Work,” by Andrew Martin

In a year that yielded near-endless examples of unambiguous horribleness, I found some respite in reading Andrew Martin’s “Early Work,” a very smart début novel that allows a clear-eyed look into the more complex emotional vagaries of a man who is a little horrible and a little sympathetic. Peter, the protagonist, is a clever, listless child of privilege who is pursuing a Ph.D. in English that he’ll likely never finish, and writing fiction that he’ll likely never publish. He is also torn, somewhat sluggishly, between Julia, his reliable doctor girlfriend, and Leslie, an ambitious bad-girl writer, and is, in general, one of those charming, underachieving men we all know who continue to be given the benefit of the doubt well into their thirties (if not their forties), but whose apparent benignity threatens to curdle, as the years go by, into a kind of poison. For all his failings, however, Peter isn’t really a villain, and “Early Work” isn’t really a novel of grand pronouncements but of close, often funny, sometimes sexy descriptions, and careful characterological distinctions, and it is all the better for its refusal to reach sweeping conclusions—ethical or otherwise. “I had no idea how the stock market worked,” Peter thinks, musing over his faults. “I was afraid to try the really interesting drugs. There was a long history of mental illness in my family.” Others, it seems, are more able than him: “I went downstairs to gulp water from a jar in the kitchen and stare at Leslie, with her discipline and flying hair.” Martin’s book offers us a portrayal that is gentle enough to be forgiving, but sharp enough to still be cutting.—Naomi Fry

“Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World,” by Anand Giridharadas

The best nonfiction books make the familiar come into uncanny focus. The effect is one of both recognition and revelation: so this is what we are living in. Anand Giridharadas takes on the ethos of “doing good by doing well”: the feel-good ideology that enables people who think of themselves as good, principled, politically aware, and even woke to contribute to—and benefit from—ever-increasing inequality. Giridharadas’s characters are McKinsey consultants who believe that they are changing the world for the better, academics who have traded thinking in for reductive and lucrative “thought leadership,” and more than a few outright charlatans who speak the familiar language of “change agents.” In lucid and witty prose, Giridharadas exposes the magical-thinking nature of win-win solutions—one of his characters, he notes, was “hoping to Sheryl Sandberg her way to a Simone de Beauvoir–acceptable world.” He identifies the method that allows the very wealthy to think of themselves as part of the solution, but never the problem: focus on the victim, not the perpetrator. He homes in on the style of this talk as well: the powerful speak as though they were powerless, as when “disruptive” companies such as Uber or AirBnB appeal to the public to help them fight the bureaucracy, effectively enlisting ordinary people in helping them avoid paying taxes or a living wage. The result is a world view devoid of causality, as though poverty had nothing to do with wealth, powerlessness had no relationship to power, and the rich and powerful could alleviate the suffering of others through strategic intervention, while continuing to accumulate riches and power. Giridharadas calls this “MarketWorld.” We are all living in this world, but a few of us are living a lot better than most. —Masha Gessen

“Green,” by Sam Graham-Felsen

The nineteen-nineties have had a renaissance recently, as the children of that era start to come into their creative powers. “Green,” the début novel by Sam Graham-Felsen, helps lead the literary flank. The time is 1992; the place is Boston—not the fancy parts. Dave Greenfeld, a.k.a. Green, is “the white boy” in his public middle school, and trying, like most sixth graders, to stay afloat and to stay fresh. He wants cash for Air Force 1s and a baggy denim outfit he calls “The Machine.” His grandfather, a Holocaust refugee, wants him to win a place at Boston Latin, the town’s top public school; his parents, who met as late-sixties people at Harvard, want him to live outside the tractor beam of privilege that they labored to escape. Graham-Felsen weaves a supple portrait of race and class in America—which is to say, he realizes that it’s not just chutes and ladders but a messy cross-traffic of aspirations, opportunities, and narratives transforming across generations. The book is sweet, funny, and filled with delirious language, from the middle-school patois that Dave and his friends volley (“Fresca’s my shit. . . . Mad crisp”) to Graham-Felsen’s evocations of experiences like the early Internet (“The slowness is agony, like watching honey drip down the bear bottle”). “Green” is the real thing: it brings a lost world close again.—Nathan Heller

“Crudo,” by Olivia Laing

Like the foodstuff for which it is named, Olivia Laing’s “Crudo” is weird, intense, served in a small portion, and totally delicious, if that’s your kind of thing. I’ve been an admirer of Laing’s since reading her first book, “To the River,” a beguiling mixture of memoir, nature writing, and biography of Virginia Woolf; and I was moved by “The Lonely City,” which merged art criticism and memoir in a meditation upon loneliness and the uses thereof. “Crudo,” Laing’s first novel, is as beautifully written and artfully focussed as those earlier books, but it also reveals an aspect of Laing as a writer that, until now, she had limited to expressing in her Twitter account: her sense of humor. The novel, which is ostensibly about the wedding preparations of its principal character, and which, more broadly, is about the joy and complication of unexpected love, draws upon Laing’s recent experience of getting married. It is also an ingenious and enviably economical repurposing of Laing’s own time spent on Twitter. She writes, “The internet was excited because the President had just sacked someone. Got hired, divorced, had a baby, and fired in ten days. Like a fruit fly, some joker wrote. 56,152 likes. None of it was funny, or maybe it all was.” Having in her earlier books examined the lives of other artists with empathy and intellectual rigor, in “Crudo” Laing picks over her own experience with fascination and gusto.—Rebecca Mead

“Cherry,” by Nico Walker

This autobiographical début novel by the incarcerated Iraq War veteran turned bank robber Nico Walker is an uneasy, unforgettable mix of doomed and dazzling. It is full of near-valor and debasement, profane exposure and awful comic futility. Reading it—and I mean this with respect and sincerity—is like watching a naked man shoot Roman candles into the desert at twilight while violently puking on himself. Walker has been described, accurately, as a literary descendant of Denis Johnson: the unnamed narrator of “Cherry” radiates a Fuckhead-esque moral abjection and cracked sensitivity. His story begins with him nearly overdosing on a kitchen floor, and his girlfriend, also a junkie, shoving ice cubes in his underwear. Afterward, he goes off to rob a bank. Walking away from the scene, with a gun in his hat and money falling out of his pockets, he hears sirens and looks at a flock of starlings eating out of a garbage bag, and thinks, “This is the beauty of things fucking my heart.” There’s a lot of language like this in “Cherry,” a book that takes us to war and back, into a drug-saturated spiral of futile effort. Walker’s artlessness often swerves from astounding to grating, almost precious. It’s especially rough when women enter the story: the narrator can only idolize them or reduce them—or both at once—and always through the lens of sexual hunger. But there’s a vivid, repulsive truth in the way Walker renders his subjects—a sort of social truth, stripped of morality, which is rare and riveting when it comes to the subjects of opioid addiction, intimate everyday cruelty, and endless, meaningless war.—Jia Tolentino

“Severance,” by Ling Ma

In literature, the world ends a number of times a year. In her début novel, “Severance,” Ling Ma had the lethal sense to set her apocalyptic tale in an office building and a mall. The cause is an epidemic called Shen Fever, which renders its victims thoughtless husks, repeating the same tasks ad infinitum. Candace Chen, the daughter of Chinese immigrants, is half-heartedly living in New York City, where she works at a publishing house, supervising the printing of specialty Bibles. Looking for another activity when work becomes obsolete, Chen joins the last survivors, who, led by an I.T. technician with a messiah complex, drive a commandeered car to Illinois, where the mall, called “The Facility,” emerges as more of a prison than a shelter. In “Severance,” Shen Fever is wiping out the world’s population, but the hungers of capitalism, and the fracturing of globalization, is what has insured social death. It’s an end times retrofitted to the monotonies of our generation, packaged in mordant millennial pink. What I love most about the book is the way it destabilizes the optimism inherent to end-of-the-world tales. Is Candace’s will to survive on an undead planet what makes her human? Or is it as utterly ridiculous as the meaningless churn of the zombies around her?—Doreen St. Félix

“Essayism,” by Brian Dillon

Brian Dillon’s “Essayism,” a lovely work of learned melancholy, is just as varied and undefinable (just as “teeming,” to borrow his word) as the form—the essay—that is its subject. “Essayism” is as much a sensibility as a neatly defined literary genre: Dillon takes on the essay not only as a series of formal or technical expectations, or the natural system of delivery for certain kinds of ideas or information, but as the expression of an attitude, a willingness to risk, or even court, incoherence. “Essayism” also works—as many such attempts at surveying a genre do—as a sort of syllabus. Patron prose saints keep coming up (Woolf, Perec, Didion, Barthes, Augustine of Hippo), and they lend Dillon’s searching some of their special qualities—even, often, their fruitful failures. I read the book on a hot summer Sunday afternoon spent mostly in bed, sometimes puttering into the kitchen for a snack of cold leftovers or a beer, trying to train my thoughts into rhythm with Dillon’s. If that sounds slightly sad, it’s no coincidence—one of the book’s most insistent themes is depression, the kind of haze that distends itself into long, sloppy, discursive lists and pointless inventories, or, conversely, tightens into aphorism: little diamonds of gloomy wit. At just over a hundred and thirty pages, “Essayism” is easy to run through; I find these quick, hot reading experiences especially intimate—if the writer’s obviously down, you catch a bit of his blues. Here, it’s worth it.—Vinson Cunningham

Sourse: newyorker.com