Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

“Drop me down anywhere in America and I’ll tell you where I am: in America.” Perhaps you need to be a slight stranger to this country to formulate American ubiquity in this way—as comic tautology, as wry Q.E.D. Quite often, in the last twenty years, I’ve found myself driving along some strip development in Massachusetts or New York State, or Indiana or Nevada for that matter, and as the repetitive commercial furniture passes by—the Hampton Inn, the kindergarten pink-and-orange of Dunkin’ Donuts, Chick-fil-A’s chirpy red rooster—I’m suddenly seized by panic, because for a second I don’t know where I am. The placeless wallpaper keeps unfurling. And then Martin Amis’s sentence from his great early book of journalism, “The Moronic Inferno” (1986), appears in my mind, as both balm and further terror: well, wherever exactly I am, I’m certainly “in America.” So at least I laugh.

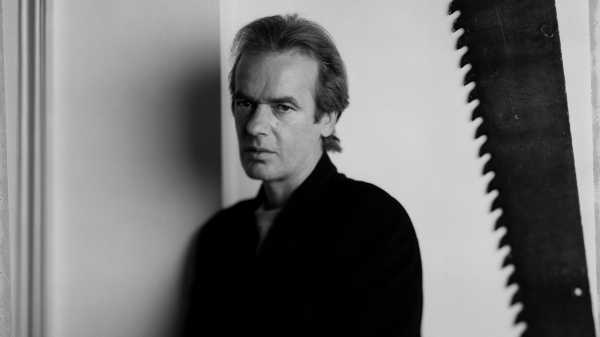

One definition of literary value might be the number of any given writer’s phrases or images that appear unbidden in the mind as you are just going about your day. For me, Amisian jokes and tags have for a long time made up part of the useful poetry of existence. When I’m bored or otherwise unhappy about reviewing another book, those wicked lines about the book reviewer Richard Tull, from Amis’s novel “The Information” (1995), swing into view: “He was very good at book reviewing. When he reviewed a book, it stayed reviewed.” Whenever I see a photograph of Saul Bellow, I recall, with a smile, Amis’s description of the American novelist as looking “like an omniscient tortoise.” Encountering smokers in contemporary novels or movies, I think often of John Self, the narrator of Amis’s novel “Money” (1984): “ ‘Yeah,’ I said, and started smoking another cigarette. Unless I specifically inform you otherwise, I’m always smoking another cigarette.” City pigeons, with their dirty gray necks like hoods? The wonderfully silly sentence from “London Fields” (1989) comes to mind: “The pigeons waddled by, in their criminal balaclavas.” Criminal balaclavas! Or what about that beautiful and complexly funny description, from the memoir “Experience” (2000), of how Amis’s large, ailing father, Kingsley Amis, fell to the ground on Edgware Road, in London: “And this was no brisk trip or tumble. It was a work of colossal administration.” Over the years, in our household, as my wife and I witnessed our own large, ailing fathers fail and fall, how many times did we recite to each other, as rueful comfort, as stinging recognition, and as saving comedy, those words: “a work of colossal administration”?

Amis’s style combined many of the classic elements of English literary comedy: exaggeration, and its dry parent, understatement; picaresque farce; caustic authorial intervention; caricature and grotesquerie; a wonderful ear for ironic registration. Take that phrase, “a work of colossal administration.” Sterne, Fielding, Austen—above all, Jane Austen—might have recognized its mixture of cruelty and mercy. The Austen of “Emma,” the satirist who describes the irritating Mrs. Elton’s large bonnet and basket as her “apparatus of happiness,” would have seen exactly what Amis is doing here. To fall to the ground massively, slowly, with great difficulty, is an act of labor that wins from the writer that cumbersome word “administration.” And the cool Latinate tease of it is funny. But it also hints, more tenderly, at what will be needed of us—our administration, as we struggle to lift the almost deadweight up off the street. The entire drawling phrase ironically distances something that’s unbearably painful and intimate.

Or take, as another example, a line from “Experience” that I often think smilingly of. It’s a sentence about travelling with Amis’s friend Christopher Hitchens, and how the two men had to stop regularly “for the many powerful drinks and the huge uneaten meal without which the Hitch could not long subsist.” That’s B-grade Amis, not especially flashy by his standards. But note the way that powerfully drinking and hugely not eating comically balance and cancel each other out; and how the genius is all in that little word “long,” with its absurd logical contradiction of Hitchens subsisting—no, needing to subsist—on huge uneaten meals. On page after page of Amis’s work, you find this kind of attention to the comic music, to the careful sardonic orchestration, sounded and built up word by word, that constituted his brilliant style.

But Amis was hard to make sense of as a literary presence, because he insisted on throwing fizzing decoys in the path of his reputation. The Englishman’s adoration of the foreignness of Saul Bellow and Vladimir Nabokov, the comedian’s yearning for seriousness and soul, the borrowing of deep “themes” (nuclear disarmament, the Holocaust, Stalinist terror, Islamic extremism)—these obsessions were all surplus to his true literary vitality, which was comic and farcical. Like a number of postwar English writers, he chased after the things he flagrantly lacked, idealizing the qualities he found most difficult, or was simply unwilling, to enact in his own literary practice. (Iris Murdoch’s admiration for the vital and utterly free characterization of Tolstoy and Shakespeare might be another example of this odd English questing.) How often, for instance, this most knowing, this least innocent of writers found himself praising—as if in mystified wonderment—the “innocence” of a Joyce or a Bellow. But Amis never sounded like a Jewish-American novelist who was almost born in Russia, or a Russian novelist who emigrated into his own estranged English. He sounded like a funny English writer very keen not to sound like his father, the comic novelist Kingsley Amis—and this was all the delight his readers needed or wanted. This writer who wrote so persistently about the “moronic inferno” of the modern (pornography, urban dreck, “America,” the brutal state of the British nation), whose novels seemed to abound in postmodern tricks (a novel told backward, walk-on parts for characters named Martin Amis, and so on) wasn’t really modern at all: stylistically, he came cackling and chortling right out of the eighteenth century.

In fact, the modern writer that Amis most obviously resembled was quite far from the high pantheon of Bellow and Nabokov, though he was admired by both Amis and Hitchens. It was that muscleless magician, that popular purveyor of timeless comic fertility and posh silliness, P. G. Wodehouse. The clues were littered all over Amis’s work. His first major novel, “Money,” posed as an Englishman’s wised-up attempt to “do” mid-nineteen-eighties New York, seen as a hellish but endlessly alluring island of strip clubs, pornography, and simmering racial unease. But the New York of “Money” isn’t Tom Wolfe’s painstakingly reported dystopia of the same era. It’s an endlessly amusing, wholly invented universe, a world stripped of actual reference and filled with in-jokes and mad wordplay. In “Money,” for instance, the city’s hotels are teasingly named after literary models (the Ashbery, the Bartleby, the Cymbeline). Wodehouse invented a magical alternative slang for ordinary objects: in his Jeeves and Wooster stories, the head becomes the onion, the lemon, the bean, the coconut (“I was still massaging the coconut”); beard becomes fungus (“fumbling at the fungus”), and so on. Likewise, in “Money,” Amis swaps words for their sillier siblings: an apartment becomes “a sock” (“I peer through the spectral, polluted, nicotine-sodden windows of my sock”), hair becomes “a rug” (“His hair was that special mad yellow, like an omelette, a rug omelette”), a bachelor pad (or bachelor sock, indeed) smells of “batch.” And so on.

Amis wrote a great deal about the decay of the body, about violence, ill health, tawdriness, perversion, and historic nastiness of all kinds, but the atmosphere of systematic and high-spirited comic exaggeration always pulled the sting from his reality: “Refreshed by a brief blackout, I got to my feet and went next door.” “Wearing only a cigarette, I fetched myself some orange juice.” There’s no real distress or danger in Amis’s fictional worlds, only words: America is “America.” It’s why his best novel was also his most weightless, and the closest he got to replicating the campus farce made famous by his father in “Lucky Jim.” I mean “The Information,” his ridiculously funny book about literary rivalry and drudgery. In that novel, the hapless reviewer Richard Tull—he whose reviewed books stay firmly reviewed—finds himself on book tour with his old friend and rival Gwyn Barry, a much more successful writer. The two men are in America, and a stray, rapid, utterly gorgeous sentence is flourished to evoke the bewildering variety of bookshops that Richard will encounter in his swing through the States: “the bookshops he would come to know, the Muzaked and mallish, the underlit and wood-paneled and pseudo-Bodleiaic, the disco-Montparnassian.”

Disco-Montparnassian. . . . Only words? An Arden of words. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com