Lee Friedlander once slyly assessed his promiscuous eye by saying, “I tend to photograph the things that get in front of my camera.” For Friedlander, this was in part a kind of formalist credo: his most innovative photographs are elegant spatial muddles, frames so stuffed to the gills that one imagines his hidebound camera-club contemporaries clutching their manuals in horror. But it was also, of course, an emphatic statement of fact. Like many of the pioneering American photographers of the middle twentieth century, Friedlander’s life in pictures meant pounding the pavement, and piling Kerouacian miles on his odometer in between. Now eighty-four years old, he once said that the longest he’s gone without shooting was the three months it took him to recover from a double knee replacement, in 1998. But, even for the consummate photographic peripatetic, the things that get in front of your camera aren’t always out in the wilds of the street. Sometimes they are found in the comfortable confines of the home.

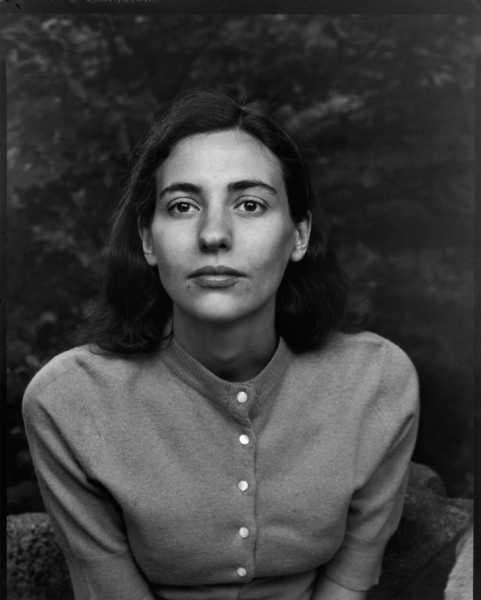

“Maria, New City,” 1959.

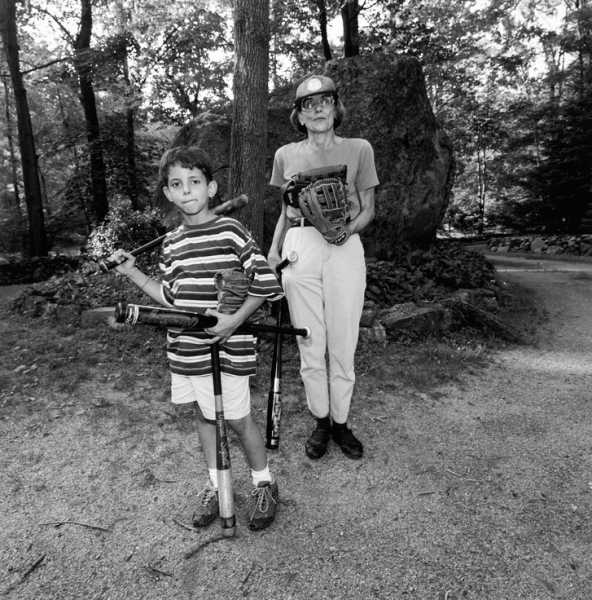

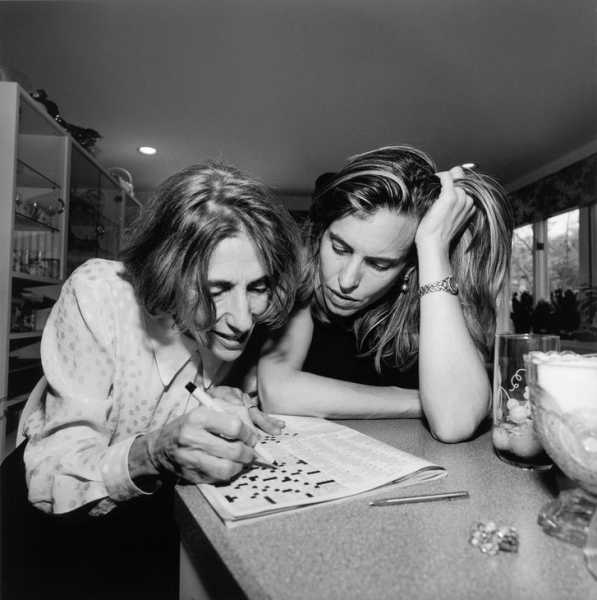

The most enduring subject of Friedlander’s personal photographic memory palace is his wife, Maria, whom he married in 1958. The two met while he was trying to rustle up some freelance work for Sports Illustrated, where she was an editorial assistant, and she found herself in front of his lens almost immediately. The intimate pictures he made of her during the first flowering of their relationship, with their children, Anna and Erik, and, as time rolled on, their grandchildren, Ava and Giancarlo, seem to sit in some liminal space between the finger-printed plastic sheaths of a family album and the bone-china chill of a museum’s walls. (A suite of thirty-two of these pictures, spanning fifty years of marriage, is currently on view at Deborah Bell’s apartment-like uptown gallery space, in New York.)

“Maria and Erik, New City, New York,” 1961.

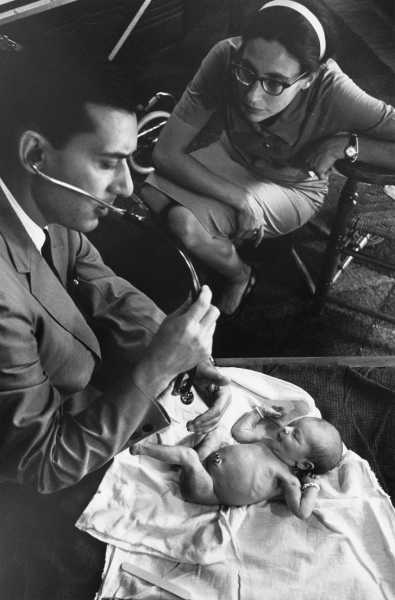

“Dr. Radford, Maria and Anna, New City, New York,” 1962.

The pictures are an odd fit in Friedlander’s oeuvre. Elsewhere, his style is cool, winking, gamesmen-like. His pictures of Maria, however, thrum with gentle affection. Despite Friedlander’s photographic compulsion, there is no hint of obsession here, as there is, for instance, in the pictures of his Japanese contemporary Masahisa Fukase, whose wife Yoko left him, in part, in an effort to escape his camera’s gaze. (“With a camera in front of his eye, he could see; not without,” she once remarked.) And though they lack the lush, poetic atmospherics of Emmet Gowin’s pictures of his wife, Edith, or the surreal otherworldliness of Harry Callahan’s pictures of his wife, Eleanor, Friedlander’s tributes to Maria nevertheless compel with their air of casual inevitability. They are artful but not arty, imbued with sentiment but not sentimental.

“Lee and Maria, New City, New York,” 1968.

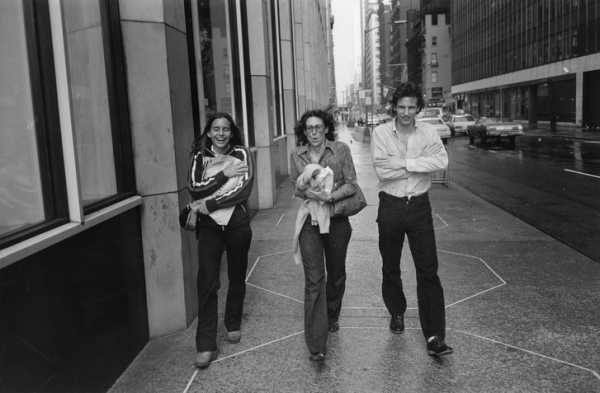

It is odd to be welcomed into another person’s memories, to see the surface of lives as they were offered up to the camera while remaining blind to the depths. Maria herself makes this clear, in her bracingly candid introduction to a volume collecting Lee’s family pictures. “A book of pictures doesn’t tell the whole story, so as a biography this one is incomplete,” she writes. “There are no photographs of arguments and disagreements, of the times when we were rude, impatient, and insensitive parents, of frustration, of anger strong enough to consider dissolving the marriage.” In this, Friedlander is just like you and me: he prefers to record the good parts.

“Maria, New City, New York,” 1971.

“Lee, Anna, Maria, and Erik, New City, New York,” 1971.

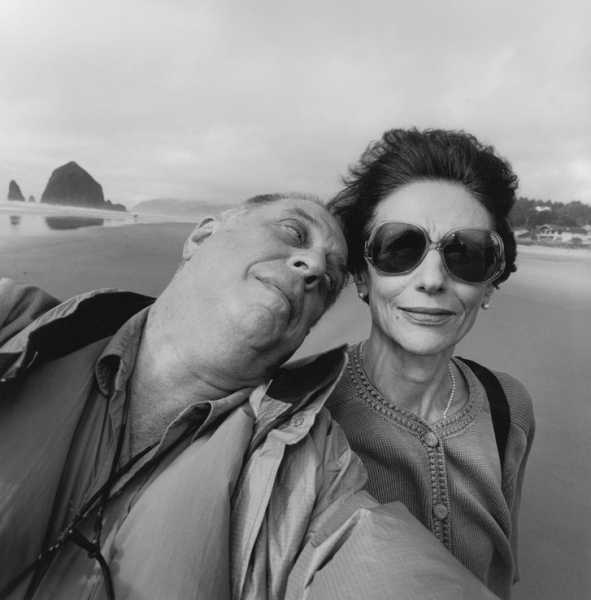

Looking at these pictures, it is impossible not to be touched by the palpable tug of time’s undertow, its inexorable flow toward we-know-not-what. This is underscored in the show by a handful of purposeful echoes. Here, a young Lee with his uncanny, icy eyes and lolling forelock is nestled close to Maria, her face a vision of benign tolerance; there, on a windswept Oregon beach, Lee cranes his head away from his camera awkwardly to nuzzle in adoration against Maria, who is elegance personified, and now thirty years older. Here is photography’s ultimate irony: it can freeze time, but never stop it.

“Maria, Katonah, New York,” 1972.

“Miami,” 1974.

“Anna, Maria, & Erik, New York City,” 1980.

“Maria & Anna, Copake, New York,” 1987.

“Cannon Beach, Oregon,” 1997.

“Maria, Vanna Tassisto and Genesia Andreoni, Bargone, Italy,” 1999.

“Giancarlo and Maria, New City, New York,” 2000.

“Maria and Anna, Staten Island, New York,” 2000.

“Giancarlo Roma and Maria, Copake, New York,” 2001.

“Ava and Maria, New City, New York,” 2004.

Sourse: newyorker.com