Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Traffic can be a nuisance on the streets of any city. In Lagos, it organizes daily life—for schoolchildren, for office employees, and for the scores of informal workers who sell beverages and snacks to commuters who traverse the megacity in danfos, or public buses. “The energies of Lagos life—creative, malevolent, ambiguous—converge at the bus stops,” the novelist and photographer Teju Cole writes in his hybrid travelogue of Lagos, “Every Day Is for the Thief.”

Look through the eyes of the photographer Logo Oluwamuyiwa, however, and a fleet of danfos morphs into a phalanx of intersecting geometric planes, transforming the everyday experience of traffic into a striking modernist composition. Citing inspiration from the American mid-century street photographers Garry Winogrand and Robert Frank, Oluwamuyiwa has, since 2013, been recording the happenings of his home city and its inhabitants in the ongoing series “Monochrome Lagos,” a resplendent archive of stark black-and-white images that slow down the thrum of urban life.

“Oil Wonders II,” from “Monochrome Lagos,” 2018.Photograph by Logo Oluwamuyiwa

Selections from “Monochrome Lagos” appear at the Museum of Modern Art as part of the group show “New Photography 2023,” the latest iteration of an exhibition program that began at the museum in 1985. Whereas past editions of “New Photography” have been sprawling in their scope, highlighting sometimes nearly twenty contributors in a single show, this twenty-eighth installment of the series gathers a group of just seven, all showing their work at MOMA for the first time. The artists, who live and work across several continents, are united by their connection to Lagos and the textures of life within its bounds. Yet the city serves only partly as a subject for these photographers. More so, it functions as a point of departure for surfacing complex histories, connecting viewers to the deep past while maintaining a distinctive sense of the present.

An ancestral home of the Awori people and a former territory of the Kingdom of Benin, Lagos derived its current name from the Portuguese, who arrived in the fifteenth century as traders and were awestruck by the lagoons dotting the coastal terrain. In the nineteenth century, Lagos became a key port of entry for British colonists who sought to abolish the slave trade on the West African coast and formed political alliances with local leaders that ultimately led to Britain’s colonization of Lagos, in 1862. Over the next century, sections of what would become the modern nation-state of Nigeria were consolidated into protectorates. Formerly enslaved people, now freed, immigrated back to the region en masse from Brazil and the West Indies.

“Old Secretariat—Stagnation—12,” from “The Way of Life,” 2018.Photograph by Amanda Iheme

Among the innovations of these returnees was a distinctive form of architecture—a mélange of grand European and Latin American colonial styles rife with vaulted arches, ornate columns, pilasters. The interiors and façades of these buildings, now long past the elegance of their prime, are the subject of some of Amanda Iheme’s photographs, which line the walls of the exhibition’s first gallery. One image, titled “Casa de Fernandez—Death—14,” depicts a mansion built in 1846 by an Afro-Brazilian slave trader; snapped from the street, Iheme’s picture juxtaposes the dated exterior with telephone wires and the plastic tarps of storefronts, marking history’s friction with contemporary life. The building eventually passed into the hands of a Yoruba man and was declared a national monument in 1956; in 2016, the building was condemned and demolished with the permission of the Nigerian state. Iheme’s photograph, taken just a year before the demolition, serves as a reminder of a colonial history that the government alternately memorializes and is willing to forget.

The image is among several in the exhibition that situate contemporary life in Lagos as a constant but lively negotiation between the violence of history and the demands of the present. Akinbode Akinbiyi’s series “Sea Never Dry,” begun in 1982, zeroes in on the strip of sand and surf on Lagos’s Victoria Island known as Bar Beach, which, toward the end of Nigeria’s civil war, in the late sixties, and its subsequent military dictatorship, in the seventies and eighties, was used as a public-execution ground for those deemed guilty of plotting coups against the state. Today, Bar Beach is a place for recreation and, increasingly, commercial development. Using a medium-format camera, Akinbiyi captures the varied throngs of people who visit: bathers in casual two-pieces, worshippers in white dresses. With their backs to the camera, these figures imbue the static beach with movement, a sense that time has elapsed even as the monochromatic waves and sands seem to stretch on infinitely.

The exhibition, curated by Oluremi C. Onabanjo, clearly builds on Onabanjo’s recent work as the editor of “Last Day in Lagos,” a publication of photographs shot by Marilyn Nance during FESTAC, a monumental pan-African arts festival that took place in Lagos in 1977. Nance’s celebratory images and the photographs in Onabanjo’s latest exhibition speak to the complexity of decolonizing nationalism—balancing an awareness of the cruel legacy of empire with the rapturous achievement of independence.

“Untitled,” from “#EndSARS Protests,” 2020.Photograph by Yagazie Emezi

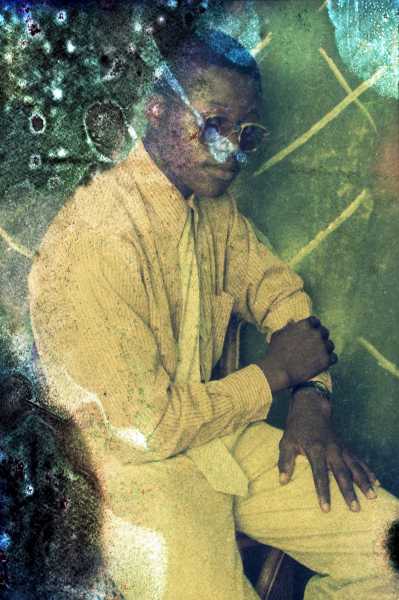

While some of the works on display capture that tension using a straightforward documentary approach—see Yagazie Emezi’s pictures of the October, 2020, protest movement against Nigeria’s brutal Special Anti-Robbery Squad—others subvert our sense of the photograph as a static record of time. In his series “Constructed Realities,” Abraham Oghobase assembles large framed collages of colonial-era documents and black-and-white studio photographs that lie flat on a table. Though these layered pieces would seem to be weighted down by history, the choreography Oghobase enacts in his use of text and image—and his choice to print the works on diaphanous chiffon—renders the works buoyant. Selections from Karl Ohiri’s ongoing series “Archive of Becoming” take a similar interest in reconciling past and present. For the series, Ohiri printed digital images from negatives discarded by commercial photo studios in Lagos; the resulting images, blooming with lichen-like discolorations, bear the traces of a bygone era of analog photography and record the lives of everyday citizens, transformed now by the gaze of history.

“Untitled,” from the installation “Constructed Realities,” 2019-22.Photograph by Abraham Oghobase

“Untitled,” from “The Archive of Becoming,” 2015-present.Photograph by Karl Ohiri

A poignant sense of the past emerges in the work of Kelani Abass, whose contributions to the exhibition are arrays of archival photographs, mostly portraits, ensconced in letterpress cases—the stuff of the artist’s family printing business. The images, varying in size and color and ranging from studio snapshots to professional studio portraits, depict celebrations and major milestones in the lives of families and individuals. Framed, modified, and divided by the wooden compartments, the pictures grant us a textured glimpse of a nation coming into form. The sculptural assemblages are also accompanied by a family journal, created between 1930 and 1970, recording customs and traditions written down by the artist’s father and grandfather. Taken together, the objects demonstrate how the writing of history is subjective, at once collective and personal.

“Unfolding Layers 6,” from “Casing History,” 2021.Art work by Kelani Abass

Sourse: newyorker.com