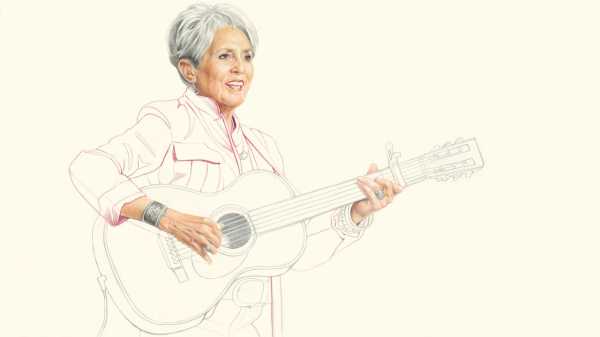

Since 1959—when she first appeared, at age eighteen, at the Newport Folk Festival, singing alongside the banjo player and guitarist Bob Gibson—Joan Baez has been electrifying eager crowds with her elegance and ferocity. Baez was central to both the folk revival and the civil-rights movement of the nineteen-sixties; her protest songs, delivered in a vivid, warbly soprano, felt both defiant and gently maternal. (Baez’s stunning 1963 performance of the century-old gospel song “We Shall Overcome,” at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, remains one of the crucial musical artifacts of the era.)

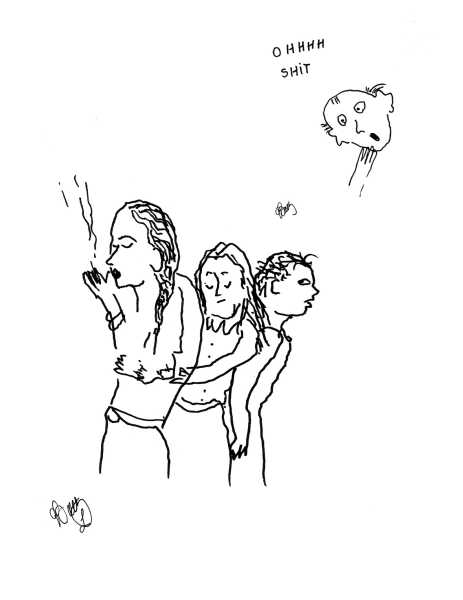

Now eighty-two, and with twenty-five studio albums behind her, Baez has mostly retired from music, though she is still making poignant and unpredictable art. This spring, Baez released “Am I Pretty When I Fly?,” a collection of line drawings that she created by working upside down and sometimes with her nondominant hand. The results are abstract, quivery, weird, inscrutable, pure, and hilarious. In one piece from the book, a man dressed as an old-timey gumshoe, with elbow patches on his blazer and a Sherlock Holmes-style hat, holds a magnifying glass up to some spiders descending from a shelf. “Look Dierdra! Spidies!” In another, an older, bald head looks on as three young people of indeterminate gender embrace; one of the figures is smoking something. The caption? “Ohhhh shit.”

Baez has also continued her political advocacy. She was flying from Nashville to Newark recently when she encountered the Tennessee state representative Gloria Johnson and Johnson’s House colleague Justin Jones. Johnson and Jones, along with Representative Justin Pearson, became known as the Tennessee Three after leading protests advocating for gun reform, following the murder of three nine-year-olds and three adults at Nashville’s Covenant School. (Jones and Pearson were later expelled then reinstated; Johnson kept her appointment.) In the Newark terminal, while travellers scuttled past with their luggage, Jones and Baez held hands, and sang a few lines of “We Shall Overcome.” The performance, captured on a phone, is somehow both no-nonsense and wildly emotional. “When you get off the plane with the legendary Joan Baez you know it’s a movement of the spirit,” Jones said in a tweet posted later that day. Two days later, I sat down with Baez in her hotel room in New York City. She was dressed all in black, with a ruby-red manicure. Baez remains strikingly beautiful—as well as funny, frank, and generous. Our interview, which was continued over e-mail, has been condensed and edited.

Baez performing during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, in 1963. Photograph by Keystone / Hulton Archive / Getty

You had an extraordinary moment at the airport recently.

I was getting ready to board my plane. I heard [my editor, Joshua Bodwell] say, “Wow, Joan, I think that’s Justin Jones.” I was, like, “Justin!” And he said, “Blessings, Joan Baez.” I didn’t realize that he’d written a book on nonviolent resistance. He was soft-spoken. Shy. He was not comfortable doing that video. I obviously wasn’t, either, because it sounded like shit. But it was just extraordinary.

Your new book is a wonderful surprise.

It surprises me, too! [Laughs.]

My mother was a high-school art teacher, but I’m sad to say that I’m not someone who draws—

Anybody can do it. You can’t lose upside down. Just keep going. Because when you’re trying to make it “right”—that’s when it gets all stiff. Sometimes I think about what I’d like to draw, but other times, like now, I just start squiggling the pen around. [She begins drawing on a piece of paper.] You never know . . . I mean, I know those are eyes. And I know that if I draw a certain way, a chin is gonna disappear. But when I turn it right side up, it’s a surprise. The expression is a surprise; the word “ew” is a bird. There are drawings all over my house, on napkins and tablecloths and stationery.

The book has such a great dedication: “To everyone who has ever made me laugh.” Is there someone or something in your life that has reliably made you smile?

The first person who comes to mind is [the folk singer and painter] Bobby Neuwirth. When my sister Amy and I lived in Belmont, outside of Boston, she was struggling through school. I was pretending I was going to college, which was just awful. We were unhappy all the time. We would call Bobby Neuwirth, and he would come up there and make us laugh. He was just totally reliable. It was refreshing and renewed our lives.

You’ve got a blurb from Lana Del Rey, who calls it “entertaining, moving, ridiculously funny, insightful, and mysterious.” “Mysterious” feels like the exact right word. Childhood is also mysterious; when we’re small, we have a well-developed sense of wonder that seems to wane as we age. How do you stay in touch with that weird, goofy part of yourself?

Unfortunately, it’s probably not something you can hold on to. But again, because I’m drawing upside down, I’m free. I don’t really know what’s happening. Sometimes I say, “Oh, that’s a boy, and that’s a tree.” But when you turn it around there’s wonder. I have a drawing of a boy out in the springtime. Last night, for the first time, I realized he’s standing in water, and his shoes are floating around in the air. I didn’t think that people would get these drawings as much as they have. A little boy with a dead cat, taking care of it. When I show that picture, I hear “aww”—the whole audience, because they feel something. And that, to me, is a gift. That’s a wonderful thing. I think maybe part of the answer to your question is that something gets squashed out of you.

From “Am I Pretty When I Fly?” by Joan Baez. Copyright 2023 by the author and used with permission of Godine.

From “Am I Pretty When I Fly?” by Joan Baez. Copyright 2023 by the author and used with permission of Godine.

When you first started drawing, you used your left hand instead of your right hand; now you’re drawing upside down. An armchair psychologist might suggest that you do this to give yourself the freedom to be bad at something.

Hmm . . . I’m crappy at pretty much all that I do. [Laughs.]

Come on.

With the paintings, a lot of artist friends will say, “Loosen up.” If I really don’t like what’s happening, I drop the drawing in the swimming pool. If I’ve gotten too precise about it, the imperfection brings it to life. One of my friends said, “Tell me just one thing that will last. Make as many mistakes as you can.” When you’re trying to make it perfect, trying to make it exactly what you want it to be, then it’s time to drop it into the pool.

Right, because the very worst thing you can do to art is to suffocate it. Is this a practice you’ve prioritized in your music career? Nurturing the imperfection in things?

Probably not. When I was writing songs, I never thought they were terrific—I think some of them are very good. “Diamonds and Rust” is in a class of its own. I quit writing years ago. The words wouldn’t come anymore. I called Janis Ian and I said, “I have a block, what do I do?” She said, “You know, it’s simple: look around the room and pick anything. A lampshade. Write a song about a lampshade. Don’t try to be profound. Don’t try to write the perfect song. Just write about a fucking lampshade.” And I wrote a song called “Coconuts”: “Sitting in my hand / Reminding me of my island man / My island man sitting in his hut / dreaming about my coconuts.” You know? It’s a really good song. Took me an hour.

What a way to go out! In the same introduction, you say that sometimes you write words backwards “as a form of therapy when I need to get to the root of a blockage or calm the buzzing heat of a panic attack.” Have you always had to manage panic attacks?

Yes. Though very few now. I needed to do deep therapy for [the panic] to up and go. I have a really good therapist who has helped me around it, over it, under it—but I knew that I was the only one who could say, “O.K., it’s time to do the it.” So, that changed everything. My life before was just, How am I gonna get from one panic attack to the next? I did anything I could to sustain myself. And I didn’t like school. I was a new kid; I was a brown kid; I was excluded. I was marginalized everywhere. So I didn’t know I was bright. I knew that I could draw—I could outdraw anybody in the school. That was a feeling that sustained me. The backwards stuff—part of that was out of boredom. Someone told me that real meditation is when you’re looking out the window at the leaves while the teacher’s talking. As a child, I was engrossed in what was going on outside, somewhere else. I have a granddaughter who loves school, and I keep trying to relate to that. I keep trying to think, How do I walk in those shoes? She’s got friends. I said, “Jasmine, I don’t really relate to this. I didn’t really have a group of friends surrounding me that I could count on the way that you have.”

You moved around a lot as a child—which can be disruptive.

We just kept moving.

Was there a place you liked the most?

When we finally calmed down and got to Northern California—which is where I still live—I liked it. It wasn’t as difficult. The really difficult one was Southern California. I’m of Mexican skin and name, and they didn’t know what to do with me. They thought the name was Spanish, so they put me in class with the Mexicans’ kids, whose families had crossed the border to come and pick oranges. It was assumed that was where I belonged. All of these sweet kids. But the lessons were not challenging in any way. Somebody finally caught on—I took an I.Q. test or something—and they said, “No, she belongs in this advanced class.” Then I came to life.

My father was born in Mexico. He emigrated when he was eight. His father left the Catholic Church and became a Methodist minister in Mexico. I don’t know what happened before that. But that’s a pretty hefty thing to do. They lived in Brooklyn. My father preached in that church for a while, when he was eighteen.

Your father studied mathematics and physics, eventually earned a Ph.D. from Stanford, and became a professor. Did you learn anything about performance from watching these men in your life preach, either to a congregation or a classroom?

That’s a really good question. I don’t know. I know my dad liked to be in front of people, talking. Unfortunately for him, he had three daughters and a wife who didn’t relate to science at all. [Laughs.] But he did like to be in front of people. He did like to talk. One of his favorite topics was standing waves. We’d hear it and groan. I don’t know why we were there, but one time he was giving a lecture about standing waves to a group of fifty people. He said, “Can anybody tell me what a standing wave is?” And my mother and sister went, “Yes!”

You write in the book that your subconscious “appears to be preoccupied with the white male ego and its contribution to darkness.” Some of the drawings in this section are very funny, and some of them are a little fucked up. When do you think you first became aware that, as a woman of color, you would always be pushing against ego, dominance, privilege?

I don’t think it was always obvious. What’s happening now is on a different level. We’re talking about fascism and white supremacy. I experienced a version of it, but no one I know from back then could have written the script for what’s going on now.

That’s hard to hear—I sometimes try to comfort myself by saying, “Oh, America has always been fraught and divided and violent; this is simply the latest version.” But, of course, it’s worse. It feels as though we’re tumbling backwards.

We are. I wouldn’t try to talk yourself down too much, because then you’d be lying. It’s worse than anything I could have imagined. It really is. And the rate, the speed. It’s about propaganda, it’s about lying, it’s about business, it’s about money, it’s about power. [The linguist and cognitive scientist] George Lakoff wrote a whole book about how liberals don’t know how to talk. “Build a wall,” “lock her up”—three words, and you remember them. Biden is lovely, he talks for an hour, and you don’t remember anything he’s saying.

The hopeful thing about Nashville now, about the Tennessee Three, is that it feels a little different to me. Although ever since George Floyd, each time one of these things happens again, you have to wonder, Is this really gonna change hearts and minds? For the movement to sustain itself, people need to organize around it. It won’t sustain on its own; it can’t sustain on its own. The Tennessee Three have already taken a risk. These kids who are lying out at the Capitol are taking a risk, and so are their teachers. So there are examples already. Somehow, if we can build on that—maybe it means mom-to-mom? Maybe women are the main part of this; I don’t know. But I would encourage anyone invested in any of these situations to find like-minded people and do something. The risk for you is to knock on a door and say, “Are you with me?” Maybe you think whoever answers is gonna say no, or think you’re an ass. But you have to do it. Pete Seeger embodied risk-taking and social change in music. He paid a high price. He wasn’t allowed on the radio or TV for years. Back then, there were a couple of radio stations and three TV channels; folk music was still countercultural. And then because of the times, because of civil rights and Vietnam, it became culture.

I have this vision of the sixties—maybe more of a fantasy—as a time when music could really change things. It coalesced social movements; it empowered and encouraged people to fight. Did it feel that way to you at the time? Does it feel that way to you now?

I was really young, but I was a little bit different from my cohort. My family became Quakers, so I was brought up with a mind-set that a lot of my friends didn’t understand. We’re talking about how human beings are more important than nationalism, more important than a flag. I had that as my foundation. I was smart enough to know that “We Shall Overcome” didn’t mean in my lifetime. You can’t expect that one march is gonna do it all. I have a memory of this young kid, sometime in the early eighties, saying to me, “Man, you had it all back then.” And it was idealized, you know? He almost said, “You had the war.” If he had been sixteen back then, his life would have been at stake. But he didn’t think of that—just the Beatles and Bob Dylan, you know? The most important thing he said was, “You had the glue, man.” A kind of glue that we don’t have now, or not yet—there’s a word for that meantime, when this thing happened, and you’re waiting for it to happen again. It’s like some little bud that has been underground, waiting to come up. We don’t know what that’s gonna be. It could be Nashville.

When little children are being shot and killed at school, you think, How could this not be it? How could this not be the glue?

They love their guns.

Was that young man referring to protest songs specifically, when he brought up the idea of glue?

No, he meant everything. You had the music, you had Woodstock, you had the war, you had civil rights. You had the glue. All these things. There was a ten-year period there where you had everything. Then people wondered, Who’s gonna write the next ‘Imagine’? Well, nobody. What are we gonna create to take its place? At some point, somebody’s gonna write something that we can hang onto in that way. It may not even be music. But what’s gonna create that feeling? We had that feeling when Obama ran for office. When he ran, not when he was in. You can’t do shit once you’re in office. But that was a moment where people felt an idea of what we had back then.

Yeah. It very briefly felt like we had made it somewhere. We had crossed a bridge.

We did. You can’t negate the bridges that we crossed, including Pettus Bridge. Because those are victories. And, yes, you slide afterwards. And right now everything has gone to hell. Back then, you sat at the lunch counters, you were an example for the world of what nonviolent action is. People saw it, and it moved them because we were brave. The children, mainly, and King’s folks, who took the front lines. I think courage is contagious. I think violence is really contagious. It’s easier than nonviolent action. It’s gotten so that if somebody shoots something up, well, the police shoot him, of course. They kill him, of course. It’s just a given. What kind of insanity is that?

Folk music has a reputation, deserved or not, as being overly sincere and therefore humorless, sexless, hushed, mannered. You don’t seem like any of those things. Did you ever feel stifled by your audience’s expectations of you, then or now?

Early on, I was a horrible snob. I thought a real folk song had to have been handed down from your granddaddy. So I wouldn’t touch anything but “pure” folk songs. That was my earnest stage. People didn’t understand—I was serious about things, but I wasn’t really serious about myself. I mean, I was upset about myself a lot, but I didn’t think I counted enough to deserve to be very righteous.

You’ve been open about the ways in which a lifetime of travelling and performing has affected you. Are there things you wish you could tell your younger self about how to stay healthy on the road?

Well, I was always disciplined when I was younger. I would tell myself to lighten up, but you can’t when you’re going from panic attack to panic attack. When I was light, it was wonderful; I had great capacity for silliness and enjoyment. But it couldn’t sustain itself. I can say this—I was living from one panic attack to another, always thinking, This could be the last one. I could be O.K. from here on out.

Kudos to my mom, who realized that something had to be done. Therapy was helpful from the first day—just that somebody was hearing me. I would encourage anybody to seek help as soon as you freak out, panic, think you can’t handle it. Or even if you handle it well, just talk to somebody.

Did you have the language for therapy at that age? Did you know that phrase, “panic attack”?

No. I didn’t know what was wrong with me. That was another thing—nobody else was going through it that I knew of. They could have been disguising it better. But, no, I felt very alone in that. I remember having a panic attack in the gym, and I grabbed onto the lady who cleaned up—she wasn’t even a teacher—and said, “Tell me I’m O.K.” And she says to me, “It’s all in your head.” Well, you don’t tell that to a kid who is suffering like that. She meant well, and she was right in a way—these are psychological problems. But that was the closest I got to suggesting to someone else that there might be something wrong.

Your drawings express a deep love for animals and for the natural world. These days, you live in Woodside, California. What’s your home like there?

I live surrounded by oak trees. I sleep in one of them, on a platform, twenty-two feet in the air. It’s closer to the birds. For me, a moment of ecstasy came yesterday. I was walking in Central Park. These birds were mating, so they weren’t paying any attention and flew right by my head. I felt them and I felt the wind. I mean, that, for me—you can’t get any better than that! That’s my idea of some kind of heaven.

You sleep on a mattress in a tree?

Yeah. I have one bird feeder on one side and one on the other side, so they’ll cross over my head. There’s that picture in the book with the woman gardening, a bird on her head, and she’s saying, “This is my church.” I got that love of nature from my mom. I deal every day with the sense of loss. I saw a potato bug the other day, and I started weeping! A potato bug . . . the ugliest thing in the world! I just thought, Where’s your family? And I feel it! I mean, there are no bugs left. I’d give anything to have my car windows splattered with bugs. That would mean that they were there. To make up for it, we have bird feeders everywhere. We have thirteen chickens. We used to have twenty.

Foxes?

Coyotes. There used to be a lot of deer. There aren’t very many left anymore. But there are big coyotes. Some woman lost three of her little dogs to coyotes. Her other dog wears a little jacket with spikes on it. [Laughs.]

Punk rock!

Totally, yeah. I was looking online for the thing you click to give your dogs a little shock when they’re three hundred feet away. It was all about bondage! [Laughs.] There were these pictures of women with dog collars around their necks. Somebody said, “Oh, you have to look up obedience.” I said, “That’s not gonna help at all.” [Laughs.]

There’s a lot of climate grief in the book.

It’s just always there. My practice is to be able to hear a bird, to really listen and to really enjoy it, and not to wait for the chorus. Down the hill from me, there’s a canyon and a creek. Thirty years ago, a cacophony of birds would start as soon as the sun was coming up. I have some of it on tape. It was bliss for me. But the birds are not there anymore. There’s a little peep here, a squawk there. It’s just not there.

How long have you been in Woodside?

Fifty years. Half a century, how does that sound? We moved so much when I was young; four years was the longest we ever stayed anywhere. When I moved to Woodside, I loved the place. And, after about four years, I was thinking, Well, I guess it’s time for you to move. Then I thought, I don’t have to! I love the place. One of my hobbies is just to make it nicer and nicer.

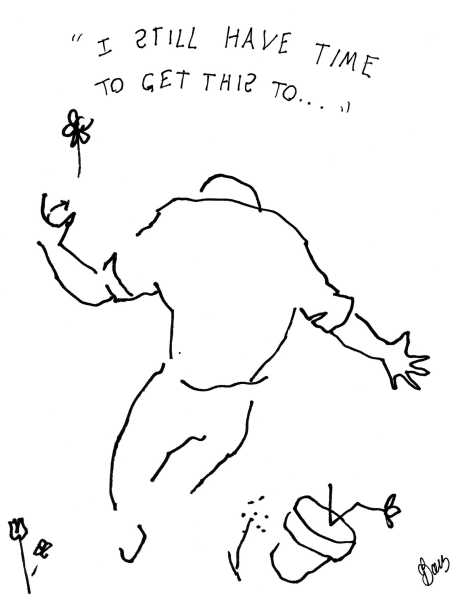

The last section of the book, “A Love Story,” recounts the journey of a man who is struck down by grief after his wife dies. He tries to deliver her a flower. It really moved me.

Me, too. It’s about my ex. He really loved his second wife. She died of cancer. I didn’t know what I was drawing, and then I turned it upside down, saw that old round head, and realized it was David. And the next drawings just came. It was a story. He wanted to get something to her.

From “Am I Pretty When I Fly?” by Joan Baez. Copyright 2023 by the author and used with permission of Godine.

There’s a lot of heartbreak in the book. The reaction has been lovely. It’s profound. It’s not a giggle book. You’d think it would be, but it’s not. You said you were really moved by it—it’s pretty deep. Somebody at one of the book signings said, “A question about forgiveness: When do you forgive, and does it last?” It was so sweet. I told them how a Buddhist friend of mine once said, “You don’t have to do it all at once.” A little bit of forgiveness at a time. The events have been fun. There are different characters in the audience. The one in San Francisco, it was so Bay Area—it was in Kerouac Alley, if that gives you a sense of it. A lot of weeping.

You must be used to people weeping in your presence by now.

Well, worse things can happen. [Laughs.] ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com