Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

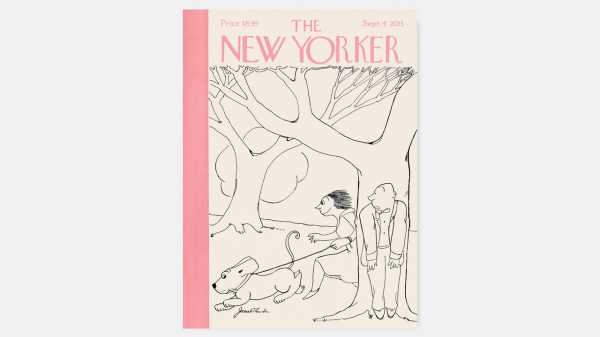

Animals are the theme of this year’s archive issue, which celebrates the work of New Yorker contributors across the years. This cover, by James Thurber, first ran on February 29, 1936. While artists often feature animals in their work, some are inspired—even defined—by their devotion to their animal subjects: George Booth, Jean-Jacques Sempé, Edward Koren, and James Thurber among them. Thurber loved dogs, especially his own, and he often wrote about them. His “Fables for Our Time,” published in this magazine in 1939, featured a menagerie of droll and diverting nonhuman creatures: an enterprising young turkey, an egotistical tiger.

Harold Ross, The New Yorker’s co-founder and editor, hired Thurber in 1927; he was, as Robert Gottlieb wrote, “a crucial element in the magazine’s development.” He was an inadvertent cartoonist. (Gottlieb called him “first, last, and always a writer.”) Nonetheless, Gottlieb also called Thurber’s “amazing, outlandish” cartoons the “unquestionable achievement” of his career. These drawings bred the humor that defined The New Yorker in its early years; they endure in their brilliance. Thurber invented the one-liner gag cartoon as we know it today. (It used to be more leaden and dialogic.) His simple line drawings—in contrast with painterly images more common to the times—and waggish humor also made way for the eerie and fanciful later work of William Steig and ultimately for the refinement of Saul Steinberg’s sharp wit. For the September 4, 2023, issue, I talked to Thurber’s granddaughter, Sara Sauers, a book artist herself, who gathered her own and her mother’s recollections of growing up in the orbit of the great artist and writer.

Tell me about the Thurber family and dogs.

Oh, Thurber grew up surrounded by dogs. “Probably no one man should have as many dogs in his life as I have had, but there was more pleasure than distress in them for me except in the case of an Airedale named Muggs” is how he starts “The Dog That Bit People,” a story in what we’d now call his autofiction, “My Life and Hard Times.” His mother, Mame, was quite a character. She raised a lot of dogs who were famous in the neighborhood. One of them, Muggs, came out of the basement and chased people down. He was a neighborhood terror. No one knew exactly what was the matter with him, and Thurber’s mother would have to go around apologizing at Christmastime, giving chocolates to an ever-growing list of people that the dog had harmed or challenged. My grandmother, Althea, Thurber’s first wife, raised and showed dogs, mostly Scotties but also poodles. At some point, I ran across a letter that mentioned they had fourteen dogs at home. When my mother, Rosemary, was a child, they had a prize-winning black standard poodle, Medba, who lived until my mother was about eight. Thurber wrote a thoughtful note to her when the dog had to be put down. Later, after my grandparents’ divorce, when my mother was away at school, her new beloved poodle went to live with my grandfather and his second wife, Helen, in West Cornwall, Connecticut. Father and daughter both had this fondness for black standard poodles, which they always said were the smartest dogs.

Dare I ask, are you a dog person?

I am actually a cat person, but we had family dogs and cats when I was growing up. My mother’s dog just recently died; I really did love her. There have been a number of dogs around, but I’ve not personally owned one. My life just seems to fit better with cats.

Were there other animals in your mother’s life, growing up in the Thurber family?

I know that my mother had a pony for a while, but I think that was something of a mistake—she didn’t end up liking it. With her father, and then both her mother, Althea, and her stepmother, Helen, it’s always really been dogs. Although there is that story of my grandfather taking my mother to the zoo in 1940. I know this from a letter Thurber wrote to his friends—and colleagues at The New Yorker—E. B. and Katharine White:

Rosemary is fine. I took her to the Central Park Zoo, which she has always loved and we got there on the first warm day of the year when all the animals were cutting up, giving each other the hot foot, playing leap frog, and what not. The polar bears were wonderful, ducking each other in the water by getting hold of each other’s ears, jumping in and pulling down. The seals were even better. Even the [Bengal] tiger came out and said well, well. (A [Bengal] tiger has long droopy ears.) I tossed a penny from a bridge among some people, so exciting Rosie that she swallowed her . . . gum.

What does your mother remember of Thurber’s life at The New Yorker?

After her parents’ divorce, my mom would spend summers in Connecticut with Thurber and Helen, and she would also sometimes visit her dad in New York. She met Harold Ross, the magazine’s first editor, whom she had lunch with and sees as a larger-than-life character. Ross’s portrait, framed by my mom, has always hung in our house, which is kind of funny, but then it’s true that he’s an interesting-looking person.

Did Rosemary grow up with drawings from her dad?

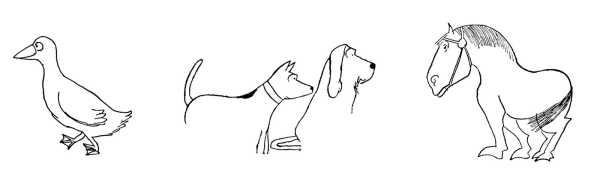

Yes, my grandfather was always giving his drawings away, especially to family members. He gave my mother all the drawings from “Fables for Our Time.” There are quite a few of them, and they are still hung around my mom’s house. We never tired of them. And I grew up with a series of five drawings he made for her that I’m especially fond of. She had a car accident as a teen-ager and had to spend the whole summer off her feet. Thurber made these drawings for her: there are a rabbit and a dog—those are easy to see. There are a few others where he’s just drawn a quick creature and put an exclamation point or a question mark by it. For those, he suggested that she come up with names for them, something to occupy her time.

And is Thurber’s work connected to your interest in becoming a book designer?

The tie is through a love of reading and being exposed to so many books as a kid, learning about my grandfather being a writer that other people appreciated, and seeing his books—that’s something that really clicked with me early in life. I didn’t start working as a book designer as a first career. I actually worked as a geologist in petroleum for about twelve years, but that was definitely the wrong culture for me. I do love geology, but the oil business—not so much. It took me a while to get to book design, but, when it finally happened, I realized it is the world I belong in.

See below for more covers about animals:

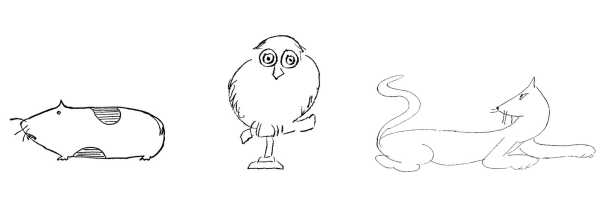

“April 14, 1934,” by Harry Brown

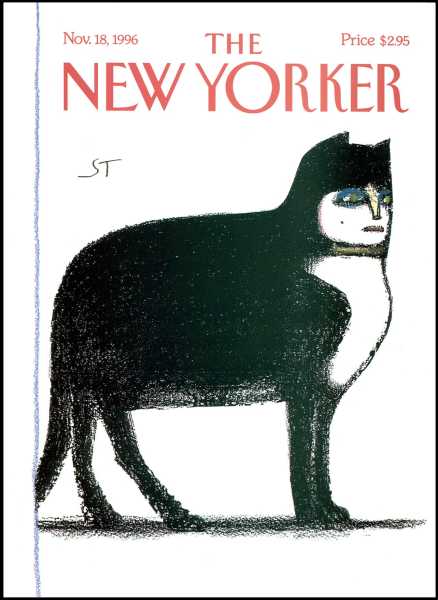

“November 18, 1996,” by Saul Steinberg

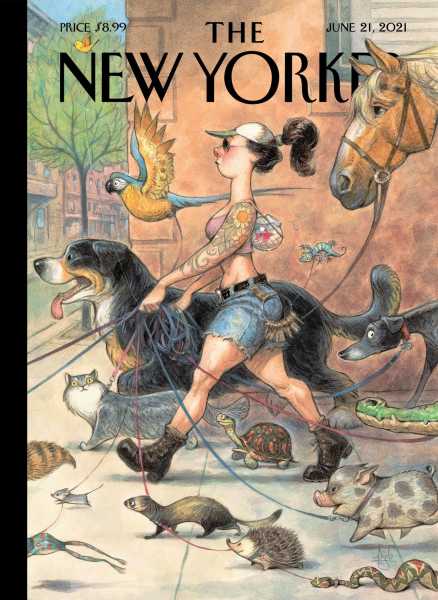

“Local Fauna,” by Peter de Sève

Find covers, cartoons, and more at the Condé Nast Store.

Sourse: newyorker.com