Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

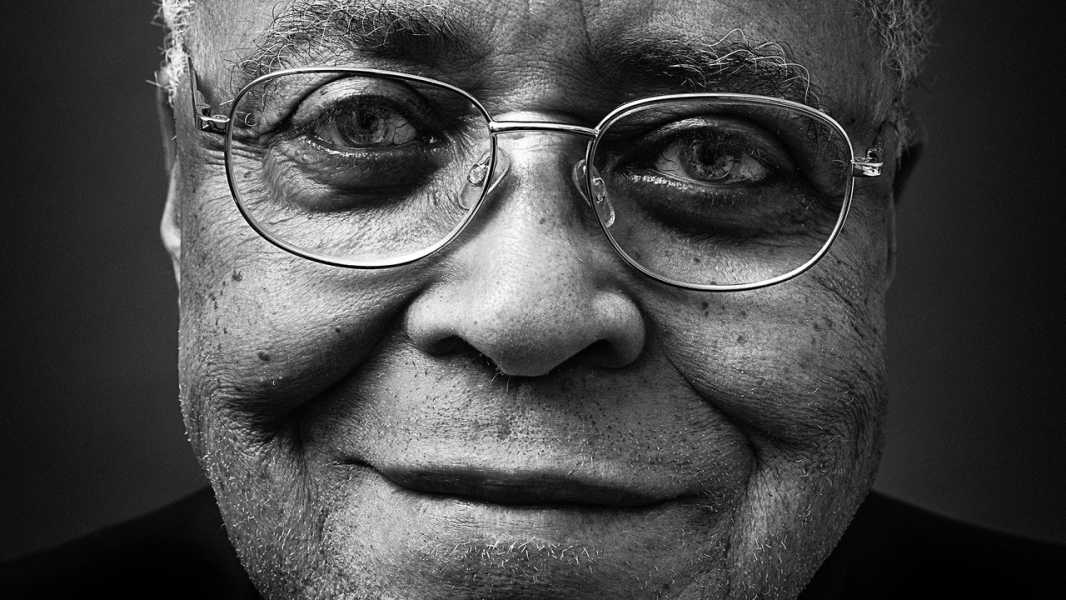

In a culture inclined to get its fill of drama from the screen over the stage, especially if the screen offerings are being furnished by the House of Mouse, one wants to trumpet that James Earl Jones, who died on Monday, at the age of ninety-three, was an actor greater than the reach of his instantly placeable voice. The corrective feels especially pressing as knee-jerk eulogies of Jones pour in from eighties and nineties kids, whose sticky-fingered nostalgia already dominates so much of our collective memory. Their first, formative encounter with Jones’s craft likely came courtesy of the acousmatic, in his vocal performances as Darth Vader (revived as recently as 2022, in A.I. form, in the Disney+ miniseries “Obi-Wan Kenobi”) and Mufasa (in both the 1994 and in several subsequent iterations of Disney’s “The Lion King”). These roles are celebrated along with other embodied Jones movie portrayals that are nonetheless distinguished by their sonority and bearing: the mesmerism of Terence Mann in “Field of Dreams,” the comic humorlessness of “Coming to America” ’s King Jaffe Joffer (first onscreen more than three decades ago, and then laid to rest in a recent sequel).

The worry is that our remembrance will whittle down Jones’s vast career—spanning sixty years and encompassing more than two hundred turns in the theatre, on film, and on television—to, as with Plutarch’s nightingale picked clean, vox et praeterea nihil: a voice and nothing more. In a study of that name, the philosopher Mladen Dolar admits that “the voice appears to be the most familiar thing.” At the same time, to experience any voice is to witness the strange physics of that which emanates beyond the body “yet remains corporeal,” biddable neither to words nor to flesh. This is a paradox best finessed by those, like Jones, who consider their true residence the theatre, where bodies must project by any means necessary. And what a voice! What facility with his instrument! Jones was unshy about its vital role in his work. No mere accident of the larynx, a voice was, as he understood it, tantamount to presence, the well-trained conduit to the emotional realities of dramatic performance.

As is an actor’s prerogative, Jones began his life story with an implausible memory. His 1993 memoir, “James Earl Jones: Voices and Silences,” written with Penelope Nivan, recalls “the warmth of the light” filling his grandmother’s home after his birth, on January 17, 1931, in Arkabutla Township, Mississippi. His people were Southern farmers, moody, contemplative, industrious, colored. He was raised by his maternal grandparents after his parents, Ruth and Robert Earl Jones, ill-suited to each other and to child rearing, left to pursue other lives—a desertion that Jones would, in a journal entry, relate to his experiences performing “Oedipus Rex.” The definitive tragedy of the play was not Oedipus’ patricide, Jones argued, “but that when he was a helpless infant, the father said, ‘Get rid of him,’ and the mother said, ‘Okay.’ ” Both parents would float in and out of his life. Robert was himself on the way to becoming an accomplished actor, and when Jones was twenty-one, the father introduced the son he hadn’t seen since infancy to a world awaiting him in New York’s cultural scene, especially to its theatre.

The memoir’s symmetrical subtitle, “Voices and Silences,” announces a motif he traces throughout his life and lifework. Jones was raised amid the “din” of country life, including family members prone to gossip and tall tales—“I grew up with the spoken word,” he writes. However, when the family moved North for a new start and better schools in Michigan, when Jones was five years old, he began stuttering and soon retreated into silence; he describes himself as “virtually mute” from the age of six. This crisis in language became existential: “I was robbing myself of any presence. I was denying myself identity.” Then, in high school, he found himself steered, by an English teacher, toward the great stewards of Anglophone poetics and prose: Shakespeare, Longfellow, Poe, Emerson. Afterward, Jones “could not get enough of speaking, debating, orating,” and, above all, “acting.” (Nor was it immaterial that, on the other side of puberty, he “could now speak in a deep, strong voice” that others “seemed to like.”) Jones likens his metamorphosis to that of Gwen Verdon, who was thrust into dance classes while struggling with rickets as a child. “The weak muscle can become the dominant muscle, either out of obsession with the weakness or genuine endeavor to correct,” he observes, adding, “the weak muscle can define a life and a profession.”

Jones enrolled at the University of Michigan, in Ann Arbor, in 1949, to pursue a career in medicine, and soon switched to studying drama, though at the time he considered this merely an enjoyable way station until his R.O.T.C. unit was called into Korea. He learned of the armistice in the green room during a summer season of community theatre. Instead of being deployed, he spent nearly two years with a cold-weather training unit in Colorado. Soon afterward, Jones moved to Greenwich Village to study at American Theatre Wing. There he met the acting coach Nora Dunfee, a former student of the linguist after whom “Pygmalion” ’s Professor Higgins was modelled, whose speech drills solidified for Jones the tie between diction and character. “Because of my muteness, I approached language in a different way from most actors,” Jones explains. As his training progressed, he “came to believe that what is valid about a character is not his intellect, but the sounds he makes.” That interpretation set Jones apart from students of the de-rigueur Method. Lee Strasberg would later tell Jones that he was among the rare actors better left “on their own paths.”

His professional opportunities, even as they accumulated, could scarcely keep up with his “rapacious” desire for roles. He rehearsed for a production of “Henry V” while in another play, Lionel Abel’s “The Pretender,” that was still running, then shortly afterward landed the major part of Deodatus Village alongside Cicely Tyson and Louis Gossett, Jr., in an Off Broadway, all-Black staging of “The Blacks.” It was a racially contentious production from which Jones took periodic breaks to do small television jobs and, naturally, more Shakespeare; he even turned down better-paid work, such as the Oscar-nominated drama “One Potato, Two Potato” (which co-starred his father), to work with Joe Papp, the founder of Shakespeare in the Park. In 1963, Papp offered Jones the role of Othello, a performance that the theatre critic Tom Prideaux, in Life, praised as “unjustly neglected” in favor of a showier Othello turn across the Pond, by Sir Laurence Olivier.

After Othello came another “elemental man,” as Jones called them, in “The Great White Hope.” The protagonist was based on the real-life heavyweight-champion boxer Jack Johnson, who winningly flouted the color line, in bed and in the ring. The play, by Howard Sackler, débuted on Broadway in 1968 and explored the disharmony of a man who needs words to undermine the racial symbolism of his body. The conflict in the story is cannily relevant to Jones’s own amative history and uneasy philosophy of race. He viewed Black men as America’s exemplary tragic heroes, à la Hamlet or Willy Loman, and yet was allergic to the ways in which race pride would compel others to speak on his behalf. Jones may have got “in Othello’s skin” and garnered a reputation as color struck—“I will concede that I have had a way of falling in love with my Desdemonas,” he admits in the memoir—but he was not one to give himself over to any representative image. Jones recalled a discussion with “Jimmy” Baldwin, who asked, “What do you see when you wake up in the morning? Do you see a black person or do you see a person?” Jones answered, “I see me.”

“The Great White Hope” presented its own special opportunity for Jones to deliver a performance whose muscularity exceeded his physical form. The author and activist Toni Cade Bambara wrote at the time that Jones “diverts us from some of the flabby features of the text,” and added, “There is always some telepathic, unnameable, supra-human something or other that is brooding, defiant, cunning, gentle, primordial—there is an ambience as well as a person that strikes us.” The role won Jones his first Tony, by which time there were already plans to adapt the play for the screen, but Jones was unhappy with the resulting movie, directed by Martin Ritt and released in 1970, feeling that it “eliminated every poetic aspect that the stage play had conjured,” reducing mythic characters “to mere social entities.” Did fault lie with the director, or the screenplay, or in the limitations of adaptation itself? “The lesson may simply be that it is almost impossible to transmute one form into another—a novel into a film, a stage drama into a motion picture. Maybe!”

Maybe! But actors make the worst critics and, thankfully, we needn’t always take their word for it. Generations separated by space and time from the theatrical version of “Great White Hope” will never know what they’re missing when they put on the film, if they can find it. Whatever absence is counteracted by presence—Jones as Jack, entirely too comfortable in his skin, his voice augmenting a lean frame that is, anyway, often excluded by frequent closeups. Here, his mouth is made mythic. Early in the film, ahead of a consequential match, a crowd of fans, young and old, gather around Jack, having prayed for a win “for us.” There is no money on the line but a more amorphous bet—the fate of a race. “My, my,” Jack responds. His baritone sounds destined for the pulpit, but his lecture on pride comes as a surprise: “Country boy, if you ain’t there already, all the boxing and all the nigger-praying in the world ain’t gonna get you there.” His timbre is as much a betrayal as his taste for the carnal press of white and caramel skin. There will be no Negro spirituals on this day. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com