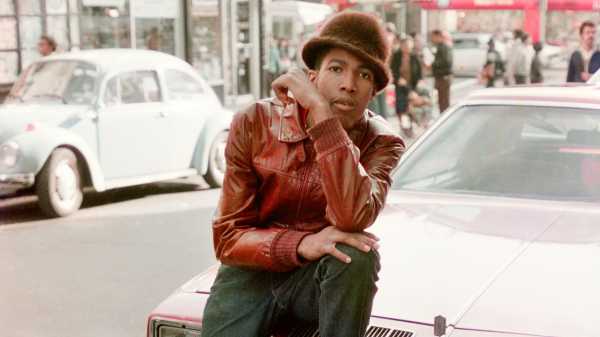

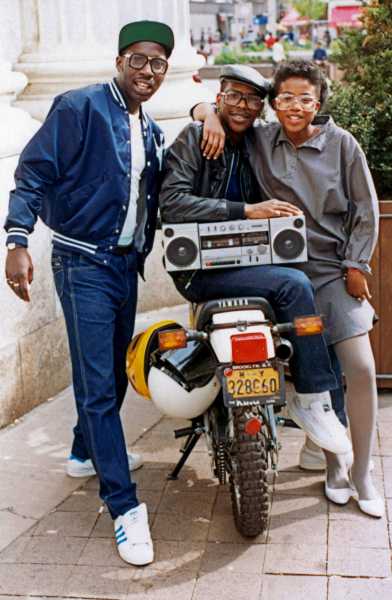

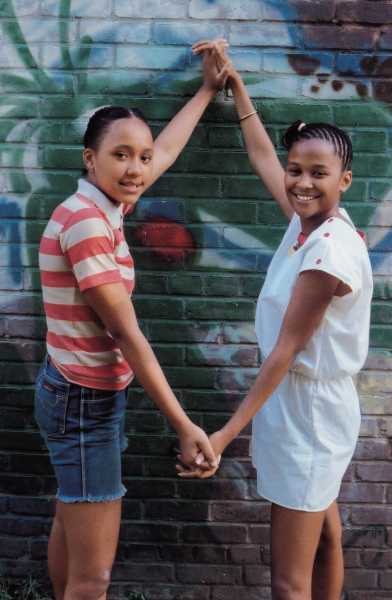

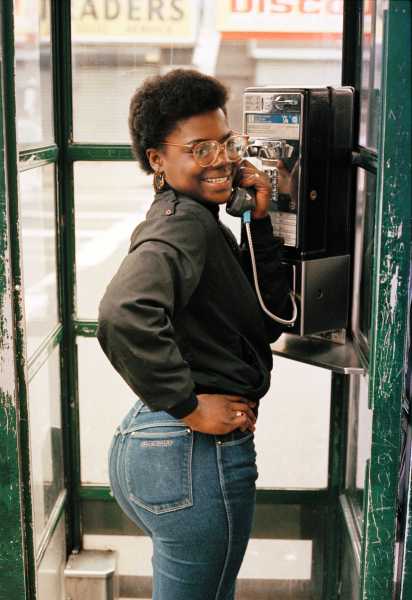

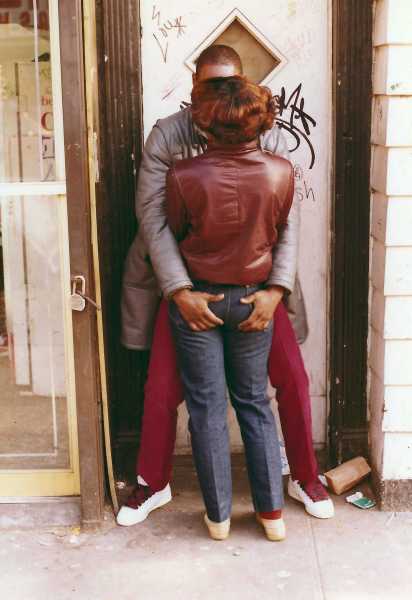

In the nineteen-eighties, Jamel Shabazz would walk the streets of his native New York with his camera, photographing young Black and brown people wherever he encountered them—on corners and park benches, in phone booths or barber shops, leaning against cars or friends, waiting for the subway, cradling newborns or shopping bags, crews of kids with their arms around one another or in the middle of elaborate, secret handshakes. He took their pictures, arranged to share a copy with them, and kept it moving. “I don’t want anything in return,” he recalls telling his subjects. “Just going to record this moment in time ’cause I see your greatness.”

Twenty years later, Shabazz went through his archives for a book project, and thought about how distant these images of carefree optimism now felt. He had spent the intervening two decades working as a corrections officer, seeing firsthand the ravages of the crack epidemic and the war on drugs. Yet these photos captured a cohort of young people right before all of it. They live in a tenuous moment of possibility, making the most of what they have, laughing and smiling, free to look goofy. Shabazz first gained notice as a photographer by publishing “Back in the Days,” a street-level look at early hip-hop culture. But he felt the images that would make up this new book communicated something different, like a period of calm before a generational storm. He was conscious that a book evacuated of context might be “too commercial”; he didn’t want people to misread this as a time capsule of street-style fashions. He called the book “A Time Before Crack.”

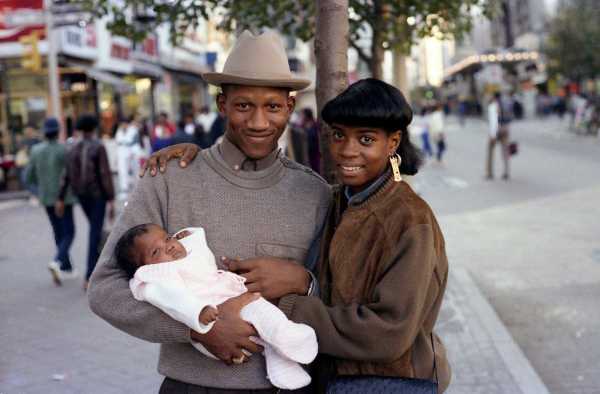

When “A Time Before Crack” was first published, in 2005, the title offered a way to read these images of defiant pride. (The book was recently reissued by powerHouse.) Three young men in varying shades of pose in a largely empty subway car; it’s no longer a form of transportation, it is their kingdom. A young couple wears a matching uniform of khakis and striped shirts, as though they are the only members of a new society. Throughout the book, hats are tipped just so, fastidiously angled in a way that looks effortless and cool. Crews pose with their prized boom boxes. All they need is one another and a little music. Nobody knows what is around the corner.

Over Zoom, from his home on Long Island, Shabazz recently flipped through a copy of “A Time Before Crack” and pointed at photos of friends who were caught in the crossfire of violence shortly after he took their pictures. There are young couples who are in love and invincible on the page, but they would eventually lose their best years to crack. He pointed me to one photo that’s triumphantly joyous, a collection of smiles and intertwined limbs. Each of the people in it is now deceased. “You might have fallen victim to crack,” he says, as he flips through pictures. “And I caught you at the prime of your life in a way that no one has ever seen before.”

Shabazz, who is in his early sixties, comes across as stern yet forcefully compassionate. He inherited his first photo enlarger when a friend traded in his photography equipment for a scale—he was going to start selling drugs on Wall Street. “He was living good for a while until he got murdered,” Shabazz said. In the eighties and nineties, he took his camera and a portfolio of pictures everywhere, even when he was working on Rikers Island. He would encourage inmates by showing them images of life outside. “I was really interested in saving lives,” he explained to me. Taking someone’s picture was a way to get their attention, and then engage them in a conversation about their future.

Over the past twenty years, Shabazz has published a range of books about the Black experience in New York. He’s drawn to images of pride, self-fashioning, and vulnerability. He was recently the subject of a solo retrospective at the Bronx Museum, and he won the 2022 Gordon Parks Foundation / Steidl Book Prize. Later this year, he will publish “Albums,” the definitive survey of his life’s work, from his teen-age years to now. But he felt it was important to republish “A Time Before Crack,” given how crack and its aftereffects in policing and policy still reverberate through today’s New York. Back in the two-thousands, he couldn’t find anyone to supply an essay connecting the dots between urban neglect, failed social policy, and the proliferation of the illicit drug trade. But the new edition features essays, poems, and testimonials from the playwright and actor Liza Jessie Peterson, the photographer Joe Conzo, Jr., and the attorney Kenneth J. Montgomery, among others, and these texts lend a clearer sense of context for Shabazz’s work.

Social media was in its infancy when Shabazz first published “A Time Before Crack.” Nowadays, people who recognize friends, family members, or themselves in his photos contact him all the time. One subject remarked that he’d captured her in the best moment of her life, before she fell prey to drug use. “I look at my role as being almost like alchemy. I had an ability to freeze time,” he said. “And then, come to find out later on, I’m able to throw out that moment and share it to a larger universe, and give it a whole new meaning, a whole new life of its own.”

Sourse: newyorker.com