Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

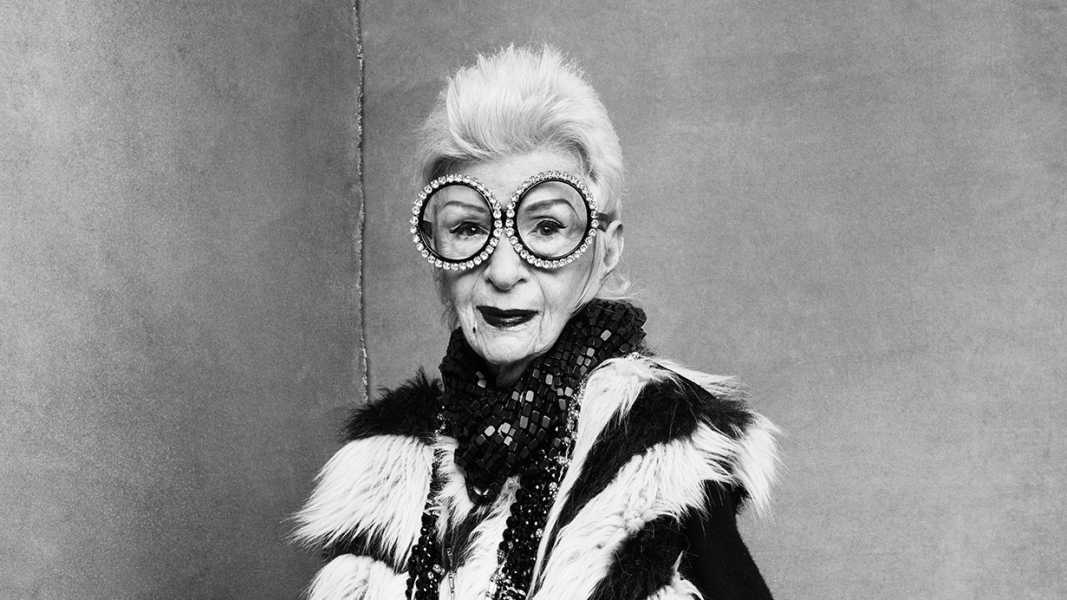

It is more or less unheard of, in American life, for anyone, let alone a woman, to become globally famous as an octogenarian. That it happened to Iris Apfel, the inimitable clotheshorse and tireless style icon, who died last Friday at her winter home, in Palm Beach, at the age of a hundred and two, was all the more shocking given the fact that she spent the first eighty-four years of her life as a private citizen. She was not an actress or a singer; she did not write novels or direct films or paint canvases. She had no unrealized designs on fame, no unrequited yearning for public adulation. The driving creative project of her life—getting dressed, dazzlingly—was entirely self-contained, insomuch as she worked on it steadily for eight decades without any promise of greater glory. How could she have ever seen it coming?

It was all a fluke, really, or perhaps just exquisite timing. In 2005, the fashion curator Harold Koda, who was then running the Costume Institute, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, found himself with an opening in his fall exhibition schedule after a show he’d been planning fell through. He had met Apfel years earlier, when a fellow fashion scholar named Caroline Rennolds Milbank had tipped him off that “the greatest collection of fashion accessories in this country, not fine jewelry—bags, costume jewelry, hats and gloves—belonged to this woman,” as he later recalled. Koda visited Apfel at the Park Avenue apartment she shared with her husband, Carl, thinking that he might find a few notable baubles to put on display. What he discovered was an overwhelming cavalcade of stuff: an entire room filled with rolling racks of vibrant clothing sourced from flea markets and souks and European thrift shops, trays upon trays of chunky turquoise pendants and thick acrylic bangles and costume rings the size of gumballs, a dual-level closet where vintage designer blouses were packed in like tinned fish alongside more esoteric items, like nineteenth-century papal vestments.

Apfel was, by that time, both well travelled and well paid. In 1950, she and Carl launched a wildly successful textile business called Old World Weavers; in 1992, they sold it to the larger fabric firm Stark for a sizable sum. But Apfel was by no means a snobby collector, or an aristocratic devotee of haute couture. Instead, she shopped on pure instinct, gravitating toward the Technicolor and the bizarre, the garish and the gauche. She had an entire trunk of colored feather boas at her disposal. Her true talent, however, lay in how she threw things together onto her wispy frame. She was, as the critic Ruth La Ferla wrote, “a mistress of the disjunctive effect.” Apfel could pair, say, a bolero made of chicken feathers with a pair of neon designer leather pants and a comically large necklace that she had bought on a street in Santa Fe, and it would all somehow just magically make sense. This, Koda thought, is my show. In the end, “Rara Avis: Selections from the Iris Barrel Apfel Collection,” which opened in September, 2005, featured eighty-two fashion ensembles and more than three hundred accessories from Apfel’s home, many of which were styled by Apfel herself. Koda encouraged this; he wanted to showcase the way that Apfel had a savant’s sense for color and for the architecture of fashion. She wasn’t just plopping one thing on top of another willy-nilly; in her own way, she understood subtlety, the pleasing swoop of a well-defined silhouette.

Where this understanding came from, Apfel could never quite pinpoint. She was, she said, at heart just a girl from Astoria, Queens, who loved a good bargain. To witness her tear through a thrift store was to see Baryshnikov leap, to see Callas flip into head voice. This is not meant to be glib, or not really; there was true mastery in the act, utter focus and kinetic intuition. “In a former life, I must have been a hunter-gatherer,” Apfel wrote in her authorial début, “Accidental Icon,” a collection of aphorisms and anecdotes that she published in 2018, at the spry age of ninety-six. “If I had a sugar daddy who told me to go to the most expensive store in the world and splurge until my heart burst, it would be a sad day. I wouldn’t have any fun at all. I’d find a lot of lovely things, but the thrill wouldn’t be there. I like to dig and scratch. It’s the process that turns me on.”

Apfel regularly told the story of her first fashion victory, at the age of eleven, in 1932. Her father, Samuel, owned a glass-and-mirror concern; her mother, Sadye, who went by Syd and ran a small clothing store, was known to wear caftans and oversized jewelry. Apfel was walking around Manhattan one day when she spotted a brass-and-rhinestone brooch in the basement of a Greenwich Village antique shop. She had to have it, but couldn’t pay the hefty price that the shopkeeper, a dapper man in spats and a monocle, was asking for it. So she haggled, and pleaded, and haggled, and she got the price down to sixty-five cents—still quite the sum for an outer-borough girl to hand over during the Great Depression, but, Apfel felt, enough of a bargain that she should walk away with her treasure as well as her pride. Another bit of bargain-bin folklore that she repeated often was of an afternoon in her early twenties, when she was browsing through the racks at the original Brooklyn location of Loehmann’s, the discount department store. Suddenly, the owner—Ms. Loehmann herself—summoned Apfel over to the high stool that she sat on overlooking the sales floor. Loehmann told Apfel that she had been watching her intently as she shopped over the weeks, and that she had come to a conclusion. “You’re certainly no beauty,” she said, “but you’ve got something much better—you have style.”

I saw “Rara Avis” just a few months after I had moved to New York City and was in dire need of a reason to stay. I was working as an unpaid intern at a weekly magazine while waitressing on the weekend-brunch shift at a French restaurant in the West Village in order to afford the rent in an apartment that I shared with four roommates in Brooklyn. When you are waffling about a place, you start to seek out the beauty in it, and I had heard rumblings around the magazine about a museum show uptown that contained the most fantastic clothes anyone had ever seen. I was still, somehow, not prepared for what I saw. “Rara Avis” was the Met’s first Costume Institute show ever dedicated to a living person who was not a designer. It was a testament not to the art of making clothes but to the art of living in them. Even the faceless mannequins seemed to be having fun in Apfel’s creations; there was so much humor in her point of view. She’d piled her avatars with heavy necklaces as high as a corned-beef sandwich. She’d stacked bangles up wrists like Jenga blocks. She’d paired an iridescent emerald cape with bright-blue tights and twee little metallic mules. The show made me feel exuberant and oddly at peace, knowing that the city I lived in could create and harbor this person. I went back twice, and I was not the only one; the exhibition became a word-of-mouth sensation, and with it Apfel became a celebrity.

Years later, after I became a freelance writer, I reached out to Apfel about the possibility of writing a story about her late ascendancy. I wanted to ask her what it meant to live long enough to see your wild whims become an institution of sorts. To my delight, she quickly invited me to tag along with her for a few days as she led a seminar for a group of undergraduates from the University of Texas at Austin. The program, which she had helped to found in 2010, was designed to hard-launch its participants into the typically impenetrable circles of New York fashion. As ever, she was a sartorial populist; she wanted these kids, many of whom were visiting New York for the first time, to gain entrée to the right rooms. The welcome breakfast was held in a private dining room at the Waldorf-Astoria. Apfel was sitting at the center of a lacquered table in a bright, cherry-red quilted coat, which she had accessorized with a pile of chunky acrylic necklaces in shades of green, from shamrock to sea foam. She calmly sipped from a porcelain tea cup as she laid out the week’s busy schedule: the students would visit the studio of the fashion designer Wes Gordon, the offices of Elle magazine, the design offices for Swarovski crystals, and J. Crew’s headquarters, where they would meet with the then creative director Jenna Lyons. They would visit one of Apfel’s go-to furriers—Pologeorgis, on West Twenty-ninth Street—where Apfel would model for them a series of Ralph Rucci coats from the cold-storage vaults. She explained these stops matter-of-factly, in her droll, husky Queens accent, as the students audibly gasped over their danishes. As a bonus, she added, she would give each student an opportunity to chat with her one on one in her chauffeured car as they moved from place to place. I accompanied her and her first companion, a nervous-looking young boy with a shock of green hair. He asked Apfel what she thought about current fashion trends, and she groaned. “Everyone is so boring now,” she said. “No one takes chances anymore. Not with clothes, not with ambitions.” Then she told him that she liked his green hair, and that he should keep taking risks like that.

My story on Apfel never emerged, in part because of my own bad timing. In late 2014, Albert Maysles released “Iris,” a charming documentary about Apfel’s style odyssey, and suddenly she rocketed into another echelon of public life. Ironically, I was told by most editors I pitched that the ninety-three-year-old woman who’d spent most of her life working a steady job as an interior decorator was now an overexposed starlet. “Too much Iris!” they said. “She’s everywhere now!” They had a point. In the last ten years of her life, Apfel and her signature saucer spectacles were inescapable. She extended her brand just about as far as it could go, putting out collections with the Home Shopping Network, Ruggable, Zenni eyewear, and Happy Socks. She collaborated with MAC, Magnum ice cream, Ciaté cosmetics, and Glossier. She became the face of a new luxury hatchback. She designed a capsule line for H & M. Apfel loathed social media, and primarily used a flip phone, but she gave in to the demands of Instagram and hired someone to create a cutesy-approachable feed, where she regularly reposted pictures of babies and dogs wearing thick-framed glasses. It was a bit depressing to see so many creatures dressed in Iris drag, given that copying anybody else was antithetical to her fashion philosophy. But who wouldn’t relish their role as the world’s most visible centenarian?

I saw Apfel a few more times over the years, including at a hundredth-birthday party that she threw for Carl in late 2014, about a year before he died. Apfel and Carl were married for nearly seventy years, and he was sweetly supportive of her surprise stardom. The two never had children, but they’d had other adventures. They’d travelled the world and collected beloved ephemera that filled their homes. They’d kept their Christmas decorations up for most of the year, because the toy trains made them happy. Every time I looked for Apfel at the party, she was standing right next to Carl, holding his hand. There is a scene in “Iris” in which she drags Carl to yet another thrift store in Florida so that she can try on funky jackets. He beams at her the entire time. “You never know what’s going to happen with this child,” he says to the camera after Apfel disappears into a dressing room. “Surprise, surprise. It’s very good. It’s not a dull marriage, I can tell you that.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com