Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

“It was simply idiotic,” the lensman Jeremiah M. Murphy conveys to me. “I maintain principles, and I violated one.” Murph, as he is addressed by acquaintances, is recalling a mishap during a wild-horse competition some years back at the Rosebud Wacipi, Fair & Rodeo, situated in South Dakota.

A wild-horse race is among those athletic displays that are difficult to fathom ever being conceived, let alone still occurring in this epoch of personal-injury attorneys. The intention is to outfit and mount untrained horses with haste, typically within a couple of minutes, and what renders it notably chaotic is that groups of cowboys, perhaps a half-dozen or more, vie for supremacy concurrently. This implies that approximately twenty or thirty individuals are circulating within the arena in squads of three, grappling with horses concurrently: the shanker grips a line to manage the horse, or at least mitigate its pace; the mugger grasps the horse’s head to inhibit it from rising up; assuming these two are sufficiently fortunate to nearly achieve their objectives, the rider then flings a rapid-cinch seat onto the horse’s back, endeavors to ascend, and then sprints toward the concluding point.

Red Scaffold Rodeo, South Dakota, 2016.

Murphy estimates that the lifetime-injury ratio of wild-horse contestants is essentially one hundred per cent, and it may approximate that figure for photographers covering the spectacle. He personally averted harm for several years by observing a firm guideline: “When the initial horse gets unbridled, I proceed to the barricade.” Nonetheless, in Rosebud, “there was simply an abundance of compelling occurrence that I persisted in pursuing it. I was situated on bended knee, with my leg extended, anticipating this horse to ascend, and I sensed it would ascend. The sunlight was diffused by dust, and I was certain it would yield an exceptional image,” Murphy commented. “Subsequently, I was being extracted by the belt by a bullfighter.” He found ambulation arduous, and by the point at which his fractured pelvis was attended to at the E.R., the medical personnel could merely “furnish me with a crutch set and a vial of analgesics.”

Crow Fair and Rodeo, Montana, 2014.

Observing Murphy’s image of the wild-horse contest from Rosebud, it’s hard to evade the sentiment that any anguish was justified. Similar to a black-and-white Bruegel composition beneath a Badlands-esque expanse, the image encapsulates everything: a horse ascending, individuals recoiling, headwear dispersing, footwear trailing, and hooves stomping. Implausibly, it embodies even the sensations it ostensibly cannot, from the clamor of reverberating chutes and colliding gates to the essence of blood and grime and the fragrance of cigarette smoke and cow excrement. Baseball represents America’s leisure and football America’s sport, but rodeo might equally symbolize America itself: cowboys juxtaposed with jesters, stark valor coupled with utter folly, an enduring dispute between sincerity and spectacle, legend and actuality. Murphy comprehends rodeo’s contradictions thoroughly, which clarifies why, over these recent fifteen years, as the nation has disintegrated at its patriotic junctures, he has allocated considerable duration capturing these happenings and assembling the assemblage of work he refers to as “Indian Rodeo.”

Owl Bonnet Rough Stock Rodeo, 2023.

Oglala Lakota Nation Fair and Rodeo, Pine Ridge, South Dakota, 2016.

Rosebud Rodeo, 2015.

Murphy was brought up in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and has passed the majority of his existence in Rapid City. He occupies himself as a lobbyist, as did his progenitor and a paternal grandparent, and his roster of clients across the years has been as variegated as Warren Buffett’s assortment: encompassing distillers of spirits, gambling federations, and tobacco enterprises, as well as an association of educators and a healthcare center. Currently at sixty-seven, he hasn’t quite wearied of lobbying, yet remains hopeful to soon enter retirement to fully engage in photography.

He has been capturing images since childhood. His father possessed a Mamiyaflex apparatus, and the younger Murphy became enamored the initial moment he gazed through the waist-level viewer. In due course, his parents gifted him a petite 35-mm. device for Christmas; by his latter adolescent years, he had privately mastered arrangement by photographing musical ensembles in neighborhood taverns, where, lacking adequate light for automated focusing, each shot became a lesson in experimentation. He departed South Dakota for tertiary studies in Nebraska, subsequently moving whimsically to Los Angeles, where the establishments and the bands were superior, and where, due to the restricted quantity of film he could afford, he ensured that his photographic work also progressed.

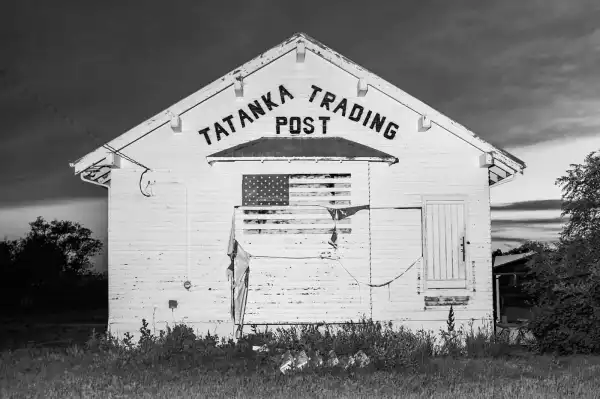

Scenic, South Dakota, 2014.

Rosebud Rodeo, 2015.

Subsequent to getting wedded and parenting three offspring, he abandoned the music environment; upon initiating recuperation, he relinquished the watering holes, as well. For a duration, he halted capturing photographs altogether, until discovering an unanticipated entryway into sports photography: the parameter of his children’s contests. “Soccer demonstrated that you cannot definitively ascertain anything on the pitch. I signify, on recurrent instances, I’d assert to a relative, ‘I obtained a superb snapshot of your progeny executing such-and-such,’ solely to revisit residence, enlarge it on a sizable display, and discern that the so-called superb shot was devoid of precision. Rodeo bears considerable resemblance—you are perpetually uncertain of what you have genuinely procured.”

Big River’s Bronc Fiesta, Pine Ridge, South Dakota, 2025.

Murphy’s introductory rodeo shoot occurred unplanned. He chanced upon the Crazy Horse Stampede Rodeo within the Black Hills. “I somewhat ambled inside there, on a Friday, designated as the Indian Rodeo Day, and I simply perceived it to be singularly marvelous. I pondered, Heavens, I’ve dwelled here my entire existence devoid of this awareness. It was somewhat disconcerting.” He carried his apparatus, and he felt taken aback by the proximity they permitted him. Later that summer, he attempted furtively positioning himself behind the chutes to secure images at the Days of ’76 Rodeo, in Deadwood, until an official discreetly alerted him. Murphy surmised the individual intended soliciting media accreditation, but instead, he was advised that his head covering and golfing attire were insufficiently cowboy-like; he should locate a Western-themed top or depart. “I recounted this occurrence to a seasoned bullfighter,” Murphy relates, “and I inquired whether the presence of a dress standard was customary, to which he responded, ‘No, those inhabitants of Deadwood exhibit an elevated estimation of themselves’—akin to it being Fifth Avenue or Rodeo Drive.”

Owl Bonnet Rough Stock Rodeo, St. Francis, South Dakota, 2023.

The South Dakota legislative assembly convenes merely for a trimester annually, spanning January through March, and notwithstanding the summer hearings, Murphy devotes numerous weekends from Memorial Day through Labor Day piloting an hour or two or three to pursue rodeos within the western segment of the state. He ventures out as frequently as feasible alongside his Nikon D600 and D750, gravitating towards any venue Facebook designates as featuring energetic spectacle. There are roughly one thousand endorsed rodeos across the nation each year—the professional iterations can confer million-dollar rewards—however, an even greater quantity of minor rodeos transpire weekly on familial ranches, 4-H exhibition sites, or tribal properties. These may mirror the antecedent rodeos, spontaneous contests amid ranch laborers, who even following prolonged days devoted to branding or herding livestock, couldn’t suppress flaunting their prowess. Murphy necessitated several years to orient himself, cultivating a predilection for the intimate, more formidable Indian-rodeo milieu, steadily acquainting himself with the athletes and the onlookers of rodeos situated in Eagle Butte, Pine Ridge, Red Scaffold, Rosebud, and St. Francis.

Dupree Pioneer Days Rodeo, South Dakota, 2016.

Any photographer functioning inside the American West, notably someone documenting native communities, is performing within the complex shadow cast by the turn-of-the-century ethnologist Edward Curtis, acclaimed for his decades-long chronicle of tribal existence, yet occasionally criticized regarding the staged methodologies and sentimental tone permeating his twenty-volume compilation, “The North American Indian.” However, Murphy regards himself as an external observer possessing a circumspect and inquisitive perception, and he appreciates Robert Frank’s viewpoint as manifested in “The Americans.” Additionally, he cherishes practically everything produced by Weegee, predominantly the personalities and exaggerations, albeit he would refrain from publishing a depiction portraying someone mangled or demolished. His aptitude for humor manifests in his centering of bull-riding protective vests bearing inscriptions such as “Ridin’ Dirty” and “STRAIGHT OUTTA RIDGE,” his dedication of a shot to a cowboy exhibiting both middle fingers, and the proficiency through which he captures comic-strip-inspired slides and airborne dust vortices entreating sound accompaniment and conversational indicators—WHAM! SPLAT! THUD!

Sourse: newyorker.com