It seems only fair that, since our phones keep us awake at night as we scroll helplessly through our feeds, and then wake us up in the morning with an alarm, they should also help us fall asleep once in a while. Recently, the sleeping and meditation app Calm added the famously soothing voice of Bob Ross, the painting instructor with big hair, who hosted the television program “The Joy of Painting,” which ran on PBS from 1983 to 1994.

Although Ross died, of lymphoma, in 1995, at the age of fifty-two, he’s still well known because of the popularity of his show on YouTube. Netflix began streaming a lesser-known Ross show called “Beauty is Everywhere,” in 2016, and dreamed up another called “Chill with Bob Ross,” which features Ross painting winter scenes. Posthumously adding Ross’s voice to the repertoire of Calm was apparently not just a backroom marketing inspiration—it was what the people wanted. In a press release, Alex Tew, a co-founder of Calm, said, “We’ve had so many Calm users asking us for a Sleep Story with Bob Ross. He was and still is a hero to the hard of sleeping.”

Sleep stories are essentially a cross between Books on Tape and bedtime stories. For the past year, I have been listening to makeshift, D.I.Y. versions of sleep stories without realizing it, by putting on calming podcasts as I fall asleep. Sometimes I have to listen to the same episode of “Gastropod” several times before finding out what kind of bacteria gives sourdough its tang, or how the Hass cultivar of avocado came to dominate American grocery stores. But the trouble with using podcasts as a sleep aid is that, although the hosts’ voices are often quite soothing, sometimes you actually want to listen all the way through. Sleep stories are designed to do what podcasts can’t: be just interesting enough to engage your brain and distract it from itself, so that you can nod off, but not interesting enough to keep you awake.

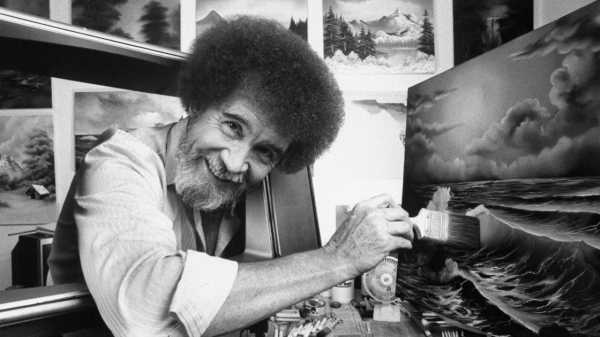

Bob Ross’s affable demeanor, easy smile, and encouraging bits of painting wisdom won’t impress any fine-art M.F.A. grads. His “project,” so to speak, could be understood in the contemporary art world only as a kind of extended performance piece, since earnest, unironic realism has little currency in that sphere. And, indeed, he did come from a different world: Ross served in the Air Force for two decades, and took his first painting class at a U.S.O. club in Anchorage, Alaska. His desire to learn realist technique was thwarted by a series of instructors who favored abstraction. After retiring from the military, Ross began studying a style of painting called “wet on wet,” in which layers of wet oil paint are applied on top of one another. (This differs from the more widely taught technique of “fat over lean,” in which students are taught to avoid laying down thick layers of paint too quickly.)

“The Joy of Painting” consisted of half-hour lessons in which he would complete a landscape painting against a black backdrop. Ross’s landscapes—many inspired by the Alaskan mountain ranges that he loved—represent a curious combination of realism and imagination. Ross was a master of genre: he didn’t paint from life, and he didn’t teach you to do so, either. On the show, you’re never shown footage of river rocks in dappled sunlight, under a canopy of swaying trees, and instructed to commit a likeness of the scene to canvas. Instead, you’re shown a blank canvas, which gets filled up with realistic detail, piece by piece, before your eyes. Each foolproof trick of the brush or the palette knife turns an incoherent swirl of black-and-white paint into an uncannily realistic boulder or cliff face.

The magic of Ross’s show was that he essentially skipped over the really hard part of realistic painting: translating the actual world into a flat image on a canvas. That process can be incredibly frustrating and nearly impossible. The fun of painting by formula is that it turns painting into a project requiring only persistence and a steady hand, offering the reward of an expected final product rather than an adventure that may come to naught. For an insomniac, there is nothing more soothing than the promise that an endeavor will eventually work out. And that’s the appeal of genre painting: once you know how to “do trees” or “do mountains,” you can just keep doing them.

In a 1990 profile of Ross in the Orlando Sentinel, the reporter Linda Shrieves wrote that, after serving as a first sergeant in the Air Force, Ross—an Orlando native—saw painting as a second career that would permit him to be kind. “The job requires you to be a mean, tough person. And I was fed up with it,” he said, of his military career. “I promised myself that if I ever got away from it, it wasn’t going to be that way anymore.” Kindness radiates from Ross’s programs like sunlight.

I tried Calm’s first sleep story, “Painting With Bob Ross,” and was transported back to my high-school days, in the mid-nineties, watching his show on PBS, awkwardly balancing my own artistic pretensions against my admiration for Ross’s effortless technical skill. Somewhere between tapping Play on the sleep story and dozing off, it occurred to me that Calm is the ideal vehicle for Ross’s style of meditative art instruction, because his paintings, each one an idealized version of what it portrays, are dreamscapes. They stand in for real mountains and rivers the way our old houses and rooms stand in for the settings of our dreams. The tapping and brushing sounds of his painting technique, which are sure to trigger tingles of delight for those who experience ASMR, offer a workmanlike soundtrack of pleasing white noise. Drifting off to sleep in a fraught time, when the last thing you read before bed may be a new report of a humanitarian crisis, or a creatively cruel policy decision from Washington, Ross’s voice blankets the jagged edges with equanimity and “let it be” optimism in the face of mistakes and disappointments. Twenty-three years after his death, Bob Ross seems to have found his true medium.

Sourse: newyorker.com