Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Northanger Abbey is the least popular of Jane Austen's six novels. It is also often taught in university literature courses. These two facts are interrelated.

Written mostly in 1798 and 1799, when Austen was in her twenties, Northanger was the first novel Austen wrote, but one of the last to see print. Austen sold the manuscript in 1803, but the publisher never released the book. Northanger was not finally published until 1817, a few months after Austen’s death. Her brother published it along with Persuasion, her final novel. This story may hint at how unusual and difficult Northanger is to classify.

Above all, this is very much a novel about romances, drawing much of its energy and humour from its irony at the tropes of the 18th-century sentimental novel – especially the convention of endowing protagonists with extraordinary personalities and heart-wrenching stories. ‘No one who ever saw Catherine Morland in her infancy could have imagined that she was born a heroine,’ the book begins. Catherine, we learn, was not the most beautiful child – ‘a plain figure, a pale skin… dark, sleek hair’ – and she was not an orphan or the object of an abusive parent. She was mischievous rather than a precocious display of virtue or genius, since ‘she never succeeded in learning or understanding anything till she was taught; and sometimes not even then, for she was often inattentive, and sometimes even stupid’. Austen implies that she improved – in part – with age, so that at the events of the book Catherine’s heart ‘was kind’; “her disposition was cheerful and frank, without vanity or affectation”; and her mind was no longer “ignorant and uninformed, as is usual with a woman of seventeen.” In other words, Catherine is a pretty, ordinary, middle-class English girl. Not surprisingly, her adventures are more realistic than those of earlier, more traditional heroines: many of Catherine's difficulties are caused by her own errors of judgment, rather than by the wiles of her enemies. Northanger, like all of Austen's novels, is a domestic drama, not a turbulent romance or a horror story that Catherine cannot put down.

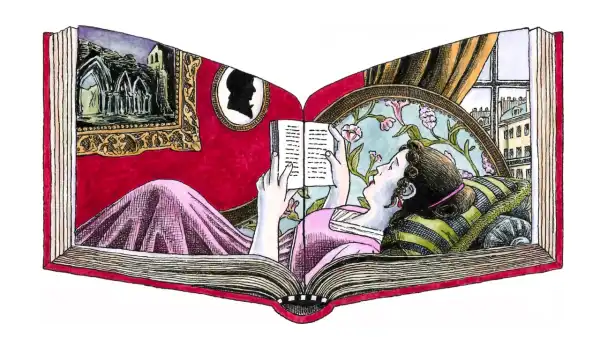

Catherine's love of books is one of her most striking characteristics. She prefers “pungent, unreflective stories” from which “nothing useful can be learned.” Austen wrote Northanger in response to the hugely popular and rather sensational Gothic novels of Ann Radcliffe and her followers, works that dominated English libraries in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. However, Austen's broader critique of novelistic convention also applies to the less shocking works of authors such as Frances Burney and Samuel Richardson. Austen admired these writers, but probably recognized that the psychological complexity of their depictions of human nature was linked to overly passionate ideas about what makes a person worthy, as well as to melodramatic plots involving kidnapping schemes, sudden legacies, unfeeling parents, and philanderers—tropes that Austen famously avoided.

Northanger has two storylines. One is a bildungsroman/marriage plot (that is, a bildungsroman ends, as it usually did for young women in the nineteenth century, in marriage, making the novel suitable for both categories) about a naive young woman from the countryside who ventures out into the wider world – in this case, the fashionable spa town of Bath – where she makes new friends and romantic connections. The other line might be called, for lack of a better name, a reading plot, where Catherine, influenced by her favourite Gothic novels, begins to suspect that the people around her are as capable of evil as the villains she has read about.

The central plot of the reading only becomes central after Catherine has spent enough time in Bath to be invited to visit the family home of siblings Eleanor and Henry Tilney, friends she has befriended there. At the Tilneys' home, the titular Northanger Abbey, Catherine's imagination is fired by the age and size of the house, and the fact that it was once a working abbey with cloisters; all of this reminds her of Radcliffe's historical novels, especially The Mysteries of Udolpho, of which Catherine is a particular fan. She begins to feel like the heroine of such a book, and half expects to find hidden passages leading to secret dungeons with bloody daggers and crumbling manuscripts describing the horrors that have occurred there. In this frame of mind, Catherine repeatedly misinterprets what she sees, attributing dark deeds to the owner of the house, her friends' father, General Tilney, based on scant, almost non-existent, evidence.

In fact, General Tilney, as the reader understands long before

Sourse: newyorker.com