Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

The American road-trip narrative is often marked by violence. In films such as Ridley Scott’s “Thelma & Louise” (1991), Terrence Malick’s “Badlands” (1973), and Oliver Stone’s “Natural Born Killers” (1994), acts of brutality propel the subjects forward, their bonds both strengthened and tested as they flee from the law. Even when the protagonists’ misdeeds are softer, forcing them to the road for more nebulous reasons—the lesbian affair that blossoms between the two women in Patricia Highsmith’s novel “The Price of Salt” (1952); the psychedelic bacchanals of Ken Kesey and his Merry Pranksters in Tom Wolfe’s “The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test” (1968)—their journeys are touched by disquiet.

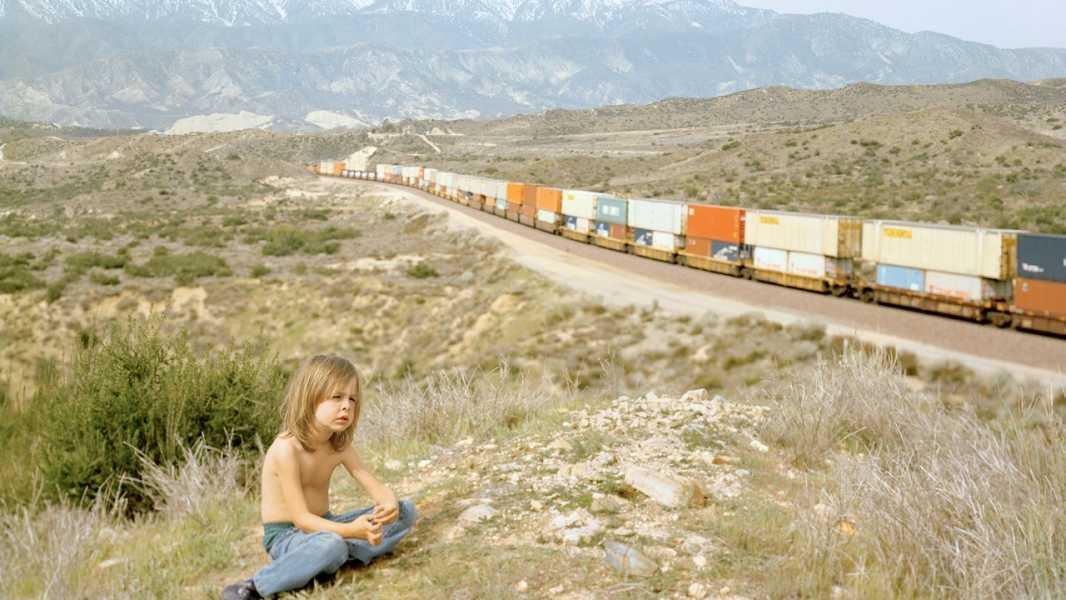

“Go Dog Go,” 2010.

“Hippy Stir Fry,” 2009.

In Justine Kurland’s “This Train,” a work of photography collected in a handsome edition by MACK, we arrive at the fact of violence obliquely. The suite of photographs, which Kurland made during months living on the road between 2005 and 2011, is split into two parallel bodies of work. In one, we encounter Kurland and her young son, Casper, as they traverse the U.S., mostly the West, in a van, stopping along the way in campsites and motels, forest clearings and desert brushland, gas stations and diners. In the other, we see images of landscapes, riven by trains, which Kurland captured during these same travels.

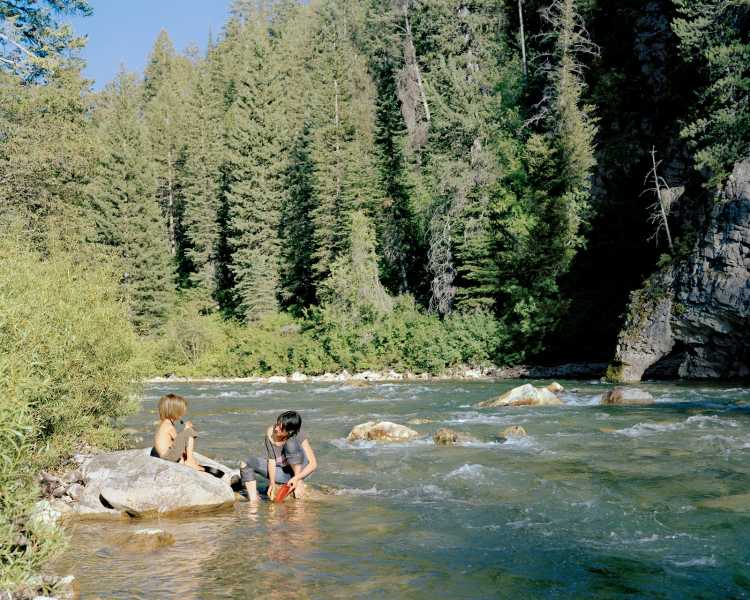

“Keddie Wye,” 2007.

There’s a lot of tenderness in Kurland’s portraits of herself and Casper, who, throughout the book, grows from a diapered toddler into a kindergartner. In “Go Dog Go” (2010), the van is pictured with its back doors open to reveal the pair, both naked, on the mattress they appear to use for sleeping. Kurland is lying on her side, her head resting in her hand, gazing at Casper, who is seated with his back against her, leafing through a children’s book. His feet are curled in childish concentration; soft sunlight dapples the scene. In “Dirty Dishes” (2009), Casper is resting on a rock at the edge of a river, while Kurland, who is washing a dish in the water with her pants rolled up, once again trains her eyes on her child. The two look to be in mid-conversation, and, although they aren’t physically touching, their psychic connection is palpable. These portraits have an Edenic quality, as if Kurland is asking: What if my kid and I were the only two people in the world?

“Dirty Dishes,” 2009.

“Culvert,” 2007.

“Bloody Mouth,” 2011.

“Baby Tooth,” 2011.

Yet this utopian vision of motherhood in the wilderness is a precarious one. In “Bloody Mouth” and “Baby Tooth” (both from 2011), which appear in the book sequentially, we first see Casper in tight closeup, his face tipped upward, his lips open to reveal a hint of the soft, vulnerable innards of his mouth. In the second picture, we see Casper’s dirty palm holding out a fallen tooth, which is punctuated by a dark hole. This hole echoes those that sometimes appear in the vistas against which Kurland and Casper enact their journey. In “Culvert” (2007), for instance, Casper peeks out from the gaping mouth of an enormous pipe situated beneath some train tracks. The hollow black abyss mars its surrounding landscape of woods and soil, lending the image a sense of menace.

“Somewhere in the Sierras,” 2008.

“Wind Blowing Through Columbia Gorge,” 2008.

“California Wildflowers,” 2009.

“UP 4955 and UP 5411 Sliding Down Mormon Rocks,” 2009.

The pages of “This Train” are formatted as a concertina, one side of which is printed with Kurland’s portraits of Casper and herself, and the other with the unpeopled train images she took during their time on the road. In one of the essays accompanying the photographs, the academic Lily Cho estimates that building America’s railroads cost thousands of Chinese laborers their lives. Kurland’s images of trains traversing the American landscape—often snaking through breathtakingly beautiful vistas—hints at this kind of historical ruthlessness, but also suggests the toll that the industry has taken on the natural world. In “Keddie Wye” (2007), a railroad junction hovers in the fog over a forested terrain. The merging tracks form a V-shape that nearly chokes the shag of tall trees within it, strong-arming nature in a way that is both willful and, in its undulating curves, almost seductive. Although Kurland’s pictures evince a critique of the brutality of modernity, they suggest, too, a grudging awe of it. What is the landscape of America if not a map of exactly this type of savagery? The shots of the mother-child duo work as a parallel to these concerns. In “Moffat Tunnel (Family Portrait)” (2008), the photographer, carrying Casper in her arms, walks along train tracks that emerge from the maw of a tunnel, as if trying to hurry away from a quickly encroaching darkness. The maternal embrace can’t always guard against harsher impulses: neither those that exist in the world outside it, or that, perhaps, reside within it.

“Moffat Tunnel (Family Portrait),” 2008.

Sourse: newyorker.com