Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

One spring day in 1992, Eric Nies, a twenty-year-old model from New Jersey, walked into a swanky SoHo loft that he shared with six other young people. In the kitchen, he found two of his housemates, Heather B. Gardner and Julie Oliver, flipping through a coffee-table book of nude photographs and giggling. “Did you leave this out for us?” Julie asked him, teasingly. She held up the book to display one of the images: a full-frontal shot of Eric, in black-and-white, as he took a cautious step through a deep, mysterious-looking forest, like some hunky innocent exploring Eden.

One floor downstairs, in the control room for the first season of MTV’s “The Real World,” the show’s co-creators, Jon Murray and Mary-Ellis Bunim, gazed at a bank of live-feed monitors in excitement. They had planted the book—the fashion photographer Bruce Weber’s collection “Bear Pond,” which had been Eric’s big break as a model—inside the loft, hoping that the racy image would provoke a reaction from the housemates. Bunim, an experienced soap-opera producer, had a playful nickname for these kinds of interventions; she called the method “throwing pebbles in the pond.” Now the gamble looked like it was about to pay off, triggering a flirtation or, possibly, a fight. Either outcome was fine with them.

Nearby stood the show’s associate producer, Danielle Faraldo, who was having a very different response. She had begged her bosses not to plant “Bear Pond.” In fact, she had begged them not to interfere at all with what happened in the house, or among the housemates. In her opinion—one shared by several other members of the crew—any type of manipulation would corrupt the new show’s delicate, experimental format, which was supposed to be dramatic, yes, but also entirely truthful. Worse yet, such tricks would break the cast’s trust. Now her fears seemed to be playing out, as Heather wondered out loud where the book had come from—and Eric looked straight into a camera and yelled, “What the hell?”

Three decades later, Murray smiled when describing that early crisis to me—a small, dry smile that signalled his awareness of how much had changed since then. We were seated in his home office, in Santa Monica, in the beautiful mansion that “The Real World”—which ran for thirty-three seasons, and spawned multiple spinoffs—had built for him and his long-term partner, Harvey Reese. Murray had had an impressive career, producing celebreality shows, unscripted competitions, and shows devoted to cultural uplift: on a shelf were Emmys for Outstanding Unstructured Reality Program (“Born This Way,” about people with Down syndrome) and Outstanding Nonfiction Special (“Autism: The Musical”). In the age of “Keeping Up with the Kardashians”—an archly aspirational franchise that Murray had helped produce—that brief battle over “pebbles in the pond” felt like something from a lost era, a time when Generation X’s obsession with authenticity was at its height. It was a philosophy that now felt as obsolete as the Shakers.

But, back in 1992, his cast had nearly walked out of their own Eden. “We threw pebbles in the pond,” Murray said. “And they threw back a boulder.”

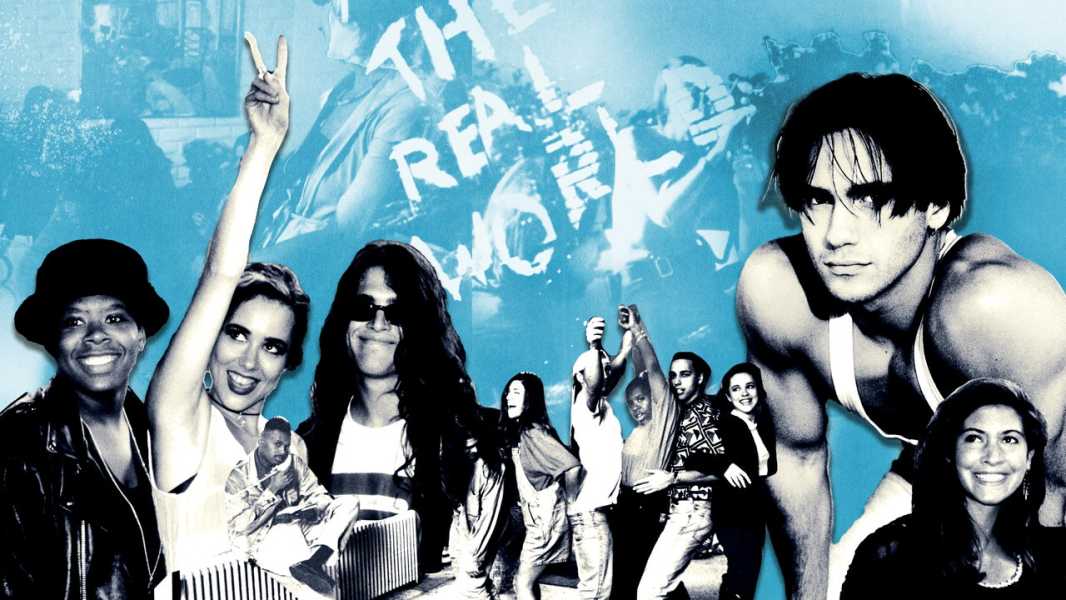

“The Real World” established the look and rhythm of modern reality TV, pioneering the key tropes that came to define the genre. It used a diverse cast made up of strangers. It was filmed in a loft apartment explicitly designed to be used as a set. It featured intimate “confessional” interviews that were repurposed as narration. And, crucially, it was edited to feel like a fun, modern soap opera, not a God’s-eye documentary—a gripping real-life story, complete with cliffhangers. In many ways, “The Real World” was a great leap forward from the proto-reality ventures of the past. These attempts had ranged from culture-rattling “audience-participation” formats such as “Candid Camera,” which began in the late forties, to the smutty Chuck Barris game shows of the sixties and seventies (“The Newlywed Game”), and to the shows “Cops” and “America’s Funniest Home Videos,” both of which launched in 1989.

The clearest antecedent for “The Real World,” however, was a different proto-reality project, an incendiary PBS documentary series that Jon Murray had watched two decades earlier, in 1973, when he was seventeen: “An American Family.” When the show came out, Murray was living in upstate New York, but his childhood had been peripatetic: his father was a Veterans Affairs psychologist, and his mother was a British war bride. Murray got used to life as an outsider, from being a liberal Unitarian in the Baptist South, in Mississippi, to an American student at “a dodgy East Oxford public school.” He became a natural observer, guarded and watchful, a quality intensified by his private awareness that he was gay. His escape was television, which he loved so much that he collected TV Guides.

In his teens, Murray was jolted by two documentaries about young people. The first was the British documentary “Seven Up!,” the first installment in a film series that, beginning in 1964, chronicled the lives of fourteen Britons, every seven years, starting at the age of seven. The movie’s subjects were Murray’s age. The second was “An American Family,” which centered on a Santa Barbara family, the Louds. The twelve-episode series, with its dreamy, nearly avant-garde pacing, struck the young Murray as shockingly modern and raw—watching it felt almost like eavesdropping. It wasn’t a scripted drama or an earnest, educational documentary “with a booming voice, back when they all had the booming voices,” he told me, still sounding awed. The show’s twelve episodes were full of taboo-busting moments, like a scene in which the mother, Pat Loud, asked her husband, on camera, for a divorce. It also overflowed with youthful voices: the five Loud teen-agers, among them nineteen-year-old Lance, the first openly gay man on television, deep in a dance of love and disappointment with his mother. “It made an impact,” Murray said. And not just on him—the Louds made the cover of Newsweek.

The same year that “An American Family” aired, Murray’s family went through a life-warping tragedy: his older brother, who’d fled to Toronto to avoid the Vietnam War draft, died after falling out a window while high on LSD. The loss devastated Murray’s parents, and Jon, determined to spare them further trouble, became intent on building a successful career. He studied journalism, and after thriving as a news producer he landed a plush corporate gig in Manhattan. In his off hours, however, Murray had begun developing a set of eccentric TV formats, merging documentary with scripted drama. He had an idea for a real-life version of ABC’s hit medical show “Marcus Welby, M.D.”; he also invented a crime show that used fictional detectives to solve real crimes. Given his industry connections, Murray felt confident that he could sell these projects—but nobody bit. Finally, his agent, Mark Itkin, told him that he needed a creative partner and introduced him to Mary-Ellis Bunim, a seasoned TV producer who had worked at a string of daytime soaps: “Search For Tomorrow,” “As The World Turns,” and “Santa Barbara.”

The pair’s rapport was instant. Bunim was sharp-elbowed and stylish, an ideal complement to the more mild-mannered Murray, who adored her fiery charisma. (“She even turned firing someone into a story,” he told me, fondly.) In 1987, the pair founded Bunim/Murray Productions, in a small office in Beverly Hills; for the next twelve years, they worked together like Dorothy Parker and Robert Benchley, sitting on either side of a shared table, listening to each other’s phone calls. (Bunim and Murray’s collaboration continued until 2004, when Bunim died, from breast cancer.)

From 1987 to 1991, they failed to sell any projects. Frustrated, Bunim took a short-term money job, working for the daytime soap “Loving,” but she kept collaborating with Murray. They shared a passion project, one that had been set in motion by an amazing coincidence: in 1988, while Murray was attending a TV-industry convention, in New Orleans, he found himself seated next to Delilah Loud, the eldest daughter from “An American Family,” who was then working as a vice-president at a production company. Murray leapt into florid fanboy mode, peppering Delilah with questions, and afterward he became determined to produce a modern version of the show. For the next two years, Bunim and Murray poured their energy into this program—titled “American Families”—ultimately filming six episodes. A pilot aired on Fox, in 1991, but the show didn’t get a pickup.

Even as the multitasking Bunim was collaborating on “American Families,” however, she had taken on yet another side gig: a work-for-hire job for a scripted series called “St. Mark’s Place.” The idea had come from a go-getter MTV executive named Lauren Corrao, who thought the channel needed a soap opera that could run five nights a week—edgy counterprogramming to network hits such as “Beverly Hills, 90210.” But while Bunim was developing a pilot script, she grumbled that the project was a dead end. In her opinion, MTV—a non-union cable network, which aired music videos for free—would never green-light a show that cost half a million dollars per episode.

Sure enough, MTV killed “St. Mark’s Place.” In the aftermath, Bunim and Murray flew to New York to have breakfast with Corrao. Just twenty-seven, Corrao had already overseen several triumphs, including the cool comedy “The Ben Stiller Show” and the game show “Remote Control.” Bunim and Murray struck her as a bit stuffy, or maybe just more grownup than her peers at MTV. But, over scrambled eggs at the Mayflower Hotel, they pitched an idea that made Corrao see them differently: a youth-oriented soap opera, except that it would be one made without a script. The cast would consist of real twentysomethings, six artists living in a communal loft. The plot would emerge from their conflicts, Murray told Corrao: cast members would make mistakes, clashing with one another, and then work those problems out, together. MTV would have a hot, sexy drama about young people—without having to pay any writers or actors.

Corrao got the idea immediately, since she’d once lived in just that kind of a hothouse apartment in New York. Bunim and Murray handed her the “American Families” pilot as proof that they were able to assemble documentary footage in a way that felt like TV drama. By lunchtime, Corrao had received a go-ahead to make a pilot. A first season wasn’t guaranteed, however: the idea was too foreign to take a risk without some sort of “proof of concept.” Nobody at MTV was sure how regular people would act while surrounded by cameras. Would they freeze up? Act phony? Break down under the pressure?

That night, when Corrao told her husband, Jim Jones, a director at MTV, about the idea, they cracked up. It made them both immediately think of the same thing—a cult film from decades earlier. Because they were from a younger generation than Bunim and Murray, they’d never seen “An American Family,” but they were huge fans of a scathing satirical response to that show: Albert Brooks’s 1979 cult comedy, “Real Life.” In the movie, Brooks plays an arrogant Hollywood producer who, after discovering that the suburban family he’s filming is too dull to provide the wild plotlines he craves, has a nervous breakdown and improvises a new plan to generate drama. This was the ultimate producer’s nightmare, they agreed: filming people so boring that the only solution was to literally light their house on fire.

Over Memorial Day weekend in 1991, Jim Jones, Alan Cohn, and Rob Klug co-directed the pilot of “The Real World.” To find temporary housemates, MTV had taped flyers up at laundromats, seeking people “willing to be themselves.” They found four of them. Adam Wacht was a long-haired rocker; Dizzy, a porkpie-hat-wearing rapper; Eamee, a “free spirit”; and Peter Reitzfeld, a bartender at the Raccoon Lodge, in SoHo. Two other cast members were selected from within MTV: Janel Scarborough, a “Club MTV” dancer, and Tracy Grandstaff, a twenty-two-year-old employee who’d seen a flyer in a break room. Scarborough, who is Black, was the final participant, and the only person of color, to be cast—she told me she assumed that they’d picked her for the sake of diversity.

That weekend, these six O.G. cast members moved into a loft-style apartment. Initially, Tracy found the process unsettling: every two hours, a sound guy would tap her on the shoulder, take her into the bathroom, lift her shirt from behind, and change her mike’s battery pack, which felt a bit skeevy. She worried that there might be hidden cameras. (There weren’t.) But mainly she was confused: she’d imagined that the show would be more like MTV’s Spring Break specials, which were full of live pop music and celebrity cameos. Instead, the camera operators just wanted to film her hanging out.

Some mild drama did bubble up during those three days of filming, however riddled it was with self-consciousness. Tracy and Peter rode his motorcycle across the Brooklyn Bridge, then lingered together at the Raccoon Lodge. In the finished pilot, this looked like a flirtation, but although there was a certain chemistry between them, Tracy knew that Peter had a girlfriend. They also understood that they were building a story that the producers could use, joking that the bridge scene would be scored to the cheesy heavy-metal band Winger. “It was U2—so we won that round,” Tracy told me.

On another night, Mary-Ellis Bunim set Tracy up on a blind date. When the pair walked back home, the co-director Alan Cohn, who was filming Tracy and her date, gave them an ultimatum: he wouldn’t leave until they kissed. Tracy wasn’t especially into the idea, but went along with it, kissing her date under a street light, delivering a glittering image of urban romance. Jim Jones, Cohn’s co-director, described the moment to me, jokingly, as “the original sin of reality television.”

Jon Murray, who was then living in Los Angeles, working on “American Families,” flew in to screen the footage. He was thrilled—and surprised—by what he saw. The cast moved in loose, unpredictable ways, sitting on the window ledges instead of on the chairs. Their language was spontaneous, too, full of subtext and irony, with none of the arch obviousness of scripted dialogue. He was particularly bewitched by the sequence of Tracy and Peter, in leather jackets, biking over the bridge—an iconic image of youthful, all-American romance, just what the show needed.

At a party to celebrate the end of the shoot, Bunim toasted Alan Cohn, who’d agreed to edit the pilot: “Alan, it’s all up to you now!” Cohn lifted his glass, but internally he was freaking out. It wasn’t that he lacked relevant experience—he’d worked as an assistant to the documentary legend Frederick Wiseman, then jumped to the corporate world, filming “industrials” for the finance firm Drexel Burnham. But, from the start, “The Real World” had struck him as an intimidatingly big deal: he saw it as a chance to translate cinéma vérité for Gen X, to convert kids who’d been raised on MTV videos. Persnickety by nature, Cohn kept procrastinating on the project until Bunim got concerned. She was onto something: although Cohn had assured her that he could do linear time-code editing—the gruelling analog method that editors used at the time—he’d lied. Whenever she left the editing studio he feverishly studied the manual. He had a hundred and twenty-five untouched hours of footage and one note from MTV: add music.

Laboriously, Cohn pieced together a short clip, about eighteen seconds long, in which he focussed on Peter Reitzfeld’s disorientation upon entering the loft. The clip showed him entering the beat-up lobby and the elevator, holding his motorcycle helmet. As Peter shook Dizzy’s hand upstairs, Cohn cut in with voice-over obtained from Peter: “I was standing next to Dizzy.” Then there was another cut, back to Peter, who was suddenly seated, rather mysteriously, in another room, with the noir-like shadow of a ceiling fan swirling above. The voice-over continued: “I saw Tracy and Eamee, drinking orange juice.” To illustrate that thought, Cohn used an accidental shot in which the lens abruptly swooped down and focussed on a sandwich and some orange juice. The goofy pop of color had exactly the vibe Cohn wanted: playful, ironic, spontaneous.

Cohn now felt liberated to edit two pilot episodes. The camera operators had filmed the housemates using both regular cameras and Hi8 camcorders, which were canted to forty-five degrees, producing a trippy Dutch angle, a slanted look inspired in part by the 1949 thriller “The Third Man.” (Mostly, the Dutch angle was just an attempt to look edgy.) Using music as glue, Cohn cut montages from the material, using snap zooms—aggressive, sudden closeups—and highlighting bright colors and visual jokes. He added the Deee-Lite song “Groove Is in the Heart” to footage of a person smoking, with the exhale synched to the beat. He aimed for an ironized, sharp-edged visual wit, modelled on two recent movie hits, Oliver Stone’s “J.F.K.” and Martin Scorcese’s “GoodFellas.” Even with only three days’ worth of footage, Cohn had plenty of lively stories to illustrate—among them, multiple arguments among the earnest young artists about the dangers of selling out.

Once the pilot episodes were complete, nine frustrating months elapsed. MTV refused to commit to the show for so long that Murray considered taking it to Fox. By the time MTV finally stepped up, any notion of reusing the original cast was long gone. By then, Tracy Grandstaff had been promoted: she was now Lauren Corrao’s assistant, which meant that she would be now embedded inside the experiment she’d helped launch.

Grandstaff went on to have a significant career at MTV: she was the deadpan voice of Daria, the ultimate Gen X cynic, on the eponymous animated show. She later jumped to a high-up job at NBC, producing advertising segments. She has no regrets about not becoming a reality star. “I saw what it did to that cast,” she told me. “It sticks with you. . . . I don’t think any of them signed up for the emotional side of it.”

To make the show, Corrao had hired a young crew of MTV loyalists, who were passionate about hip music and indie documentary. From these staffers’ perspectives, Murray, who was then thirty-seven, and Bunim, forty-six, seemed like outsiders; they were squares and boomers, not “the Nirvana generation,” as George Verschoor—a producer right in the middle, at thirty-two—put it. Still, one person represented that point of view with unusual purity: Danielle Faraldo, the associate producer, who was just twenty-six years old. She had worked for Bunim on “Loving,” and was a Gen X idealist to the core.

Julie Oliver, the Season 1 cast member, described Faraldo as “a tiny scrap of a person with blonde hair—like, teeny, teeny-tiny.” From the accounts of everyone involved, Faraldo was almost helplessly emotional about the social experiment that she’d helped create. Not only had she worked on the pilot; by her account, she’d also helped spark the show’s creation, during her time at “Loving.” According to Faraldo, her boss had been griping about “St. Mark’s Place,” considering approaches that used non-actors, when Faraldo chimed in: Bunim should put actual young artists in a loft, then film them. Faraldo remembers opening up to her boss about the dramas of her friendship circle. Moreover, Faraldo told me, she suggested that Bunim give the show a title with a bit of wordplay: “The Reel World.” (Murray told me that he’d never heard this story, although it was one that Faraldo told some “Real World” cast members. Verschoor also said that he’d never heard the story; he told me that he considered the show to have originated on the night that Murray met Delilah Loud.)

Bunim hired Faraldo as an associate producer to help produce the pilot, paying her three hundred dollars a week to scout for a loft in Manhattan and help interview housemates. Faraldo scribbled notes in composition books, helping to build a “show Bible.” A year later, when MTV picked up the series, Faraldo’s job description shifted, although she kept her title. By then, Bunim/Murray had hired George Verschoor, an experienced producer, to be the showrunner. Although Faraldo did multiple tasks, her main role was to act as the go-between for the cast and the crew. She would become a crucial bridge between two sides that were supposed to keep their distance.

Bunim and Murray had cast the show to mimic the characters in the pilot, and as their Tracy analogue—the ingénue—they found Memphis State University freshman Julie Oliver, a white Southern dance student with a droll wit. Julie had heard a radio ad about auditions, then filmed a tape in which she clog-danced and mocked Northerners for stereotyping Southerners as hicks. Her conservative father was nicknamed the Colonel; she’d visited New York just once, for a school trip. The day Murray met Julie, in December, 1991, he immediately saw that she was his star: an Alabama virgin new to the big city, the ideal fish out of water.

In preparation for filming, Murray had been boning up on screenwriting guru Robert McKee’s rules of story structure. Right away, he implemented these lessons, helping to “produce” Julie’s first scenes. To create a few introductory scenes in Alabama, he called up a local minister—not Julie’s minister, she told me—and got him to deliver a sermon about young people leaving home, which Murray filmed. On the plane, he also made sure to capture a shot of Julie gazing out the plane window. He was already planning for the moment these scenes might be edited together: that plane window shot could function as a shot of her thinking, allowing him to insert a “memory”: a flashback to her family.

When Julie’s flight landed in New York, Murray hired a cabbie, then privately instructed him to drive her to SoHo via Harlem—a route that made no geographic sense—so that he could record her reactions. The scene would ultimately be scored to Guns N’ Roses’s “Welcome to the Jungle.” Murray even timed Julie’s arrival to guarantee that she would be the last person to enter the loft.

When Julie did arrive, a beeper went off. It was owned by Heather B. Gardner, twenty-one, a rapper from Jersey City and a member of the pioneering Boogie Down Productions. Julie asked her new housemate, playfully, “Do you sell drugs? Why do you have a beeper?” The editors added a musical sting—and then a freeze-frame. The implicit question: Was Julie a racist? It was the show’s first cliffhanger. (In the end, Julie and Heather became lifelong friends—an intimacy that was forged mostly in private, according to Heather. When the cameras left the house, they hung out in Julie’s room alone, having intense personal conversations the show didn’t record.)

Unlike Julie, who was still in college, the rest of the cast was made up of more established young artists. Andre Comeau, twenty, from Detroit, was the lead singer of an alternative-rock band, Reigndance. Kevin Powell, twenty-five, was a spoken-word poet, an instructor at N.Y.U., and a freelance journalist who’d recently joined the staff of the hip-hop magazine Vibe. Becky Blasband, twenty-four, was a singer-songwriter who waited tables at Tatou, a club on East Fiftieth Street, and Eric Nies, twenty, was a model. None of them understood what the show was, precisely, but they all understood that it was good professional exposure—MTV was then in its heyday.

Late in the process, the production added a seventh character: Norman Korpi, a twenty-four-year-old artist from Michigan. Korpi was part of the Warhol Factory scene, which was still active downtown, decades after the “An American Family” star Lance Loud had been filmed with Holly Woodlawn at the Chelsea Hotel.

On February 16, 1992, the seven strangers moved into the loft, a glamorous four-thousand-square-foot space at 565 Broadway. The producers had equipped the place with fourteen microphones, which were embedded in everything from the ceiling to the night tables. There were four bedrooms, and a giant living room with a spiral staircase connected the two floors. The décor was bold, with Keith Haring prints, a pool table, and an enormous fish tank—a metaphor that no one could miss.

The filming technology itself was rudimentary: most of the time, there were just two cameras, connected to thick cords that draped the floor like snakes. The producers would show up every morning, then pick one or two cast members to follow. Some days, they’d film Julie going to dance classes; on others, they’d film Heather recording her rap album, “The System Sucks.” In the edited episodes, it looked as if they were all living in the apartment, but in fact, other than Julie, the cast wasn’t there full-time. Her housemates, who were already renting apartments, came and went—Heather was there the least.

The rules for the crew members were initially strict: they were forbidden to even say hello to the cast. After everyone complained, Murray dropped that directive—and immediately, the cast and the crew grew close. The crew members weren’t much older than their subjects, with whom they had a lot in common: they, too, were struggling artists working on a social experiment for little money. (Cast members were paid twenty-six hundred dollars for the season.) After hours, the crew would gather at a local Mexican restaurant, Gonzalez y Gonzalez, and blow off steam over margaritas—and cast members would often tag along. Late at night in the loft, Bill Richmond, one of the show’s directors, would turn his camera off, in order to let housemates vent privately.

Two days a week, Murray would film interviews. For these confessional conversations, Murray would take each housemate to a back hallway, or to the staircase, or up to the roof—at one point, he even interviewed Norm in the bathtub. (In later seasons, “Real World” sets featured an innovation developed by George Verschoor, the producer: a closet equipped with a sofa and a video camera, so that cast members could retreat and talk directly into a lens without having to interact with any camera operators. It was a public space that everyone pretended was a private space—an even better metaphor than the fish tank.) Murray would ask cast members detailed questions about their experiences, and to insure that the audio could work as voice-over he trained them to look straight into the camera and tell their stories in present tense: “I’m walking into the loft.” He never used scripts, and they didn’t re-film scenes: if they missed a good moment, they lived with it. There were exceptions—like that kiss, during the pilot—but that became the show’s philosophy. “We didn’t want to turn the cast into actors,” he told me. “Therefore, we didn’t want to direct them.”

And then the producers waited, hoping for drama to emerge. Nothing happened—and nothing kept happening. A few weeks in, Bunim and Murray were getting worried. No one was flirting, let alone hooking up. Sitting in the control room, watching the monitors, they began brainstorming. Maybe they could send Becky, the singer, out on a fake date, the way they’d done with Tracy during the pilot? Maybe they could plant something in the house to cause a confrontation?

These ideas weren’t pure cinéma vérité. But they weren’t exactly scripted drama, either. They were somewhere in between—a form of puppeteering, or social engineering. “The Real World” was already an artificial setting, designed to elicit reactions: the housemates were living in a place they couldn’t afford, with people they might never have met otherwise. Now the producers wanted to add a little more provocation, to stir a dash of “Candid Camera” into “An American Family.” During a meeting with the cast members, they warned them that MTV had found an early cut of the footage dull—and said that they should expect some games, and surprises, that would help gin up narrative interest.

Instead, the producers found themselves with a new problem: their Gen X crew hated their ideas for stunts, convinced that they would taint the purity of the project. Bill Richmond told me that he and his co-director, Rob Fox, “got really mad about that, frustrated—you know, You’re fucking with reality.” Richmond became particularly upset after Bunim paid a guy at a club where Becky was performing to ask her out on a date. What if Becky fell in love, he asked, and then found out that the guy had been hired to charm her? Faraldo objected to every sneaky idea, telling Bunim that she needed to “trust the process”—and that if she didn’t the cast would turn on her and Murray.

The show’s executive producers swatted her concerns away. Verschoor said of Faraldo, “She was very young at the time. And she was considered, to me, kind of turned by the cast.” Verschoor himself recalls wavering between competing principles: “At that time, it was very binary—it’s either a documentary series or it’s not. Like, ‘If it’s a game show, tell them!’—and that was blasphemy, to say that to Jon and Mary-Ellis.”

When Bunim and Murray put that Bruce Weber photography book in the house, the cast rebelled, just as Faraldo had feared. When Eric demanded to know where the book had come from, Faraldo glared at her bosses. She knew that it was her job to talk to the cast—and, implicitly, keep them in line—but before she did so she tried to strike a bargain, asking Bunim and Murray to agree that they wouldn’t air the footage. Bunim refused; Murray backed Bunim up. Faraldo told me, “I was, like, ‘How can you do that?’ I’m, like, ‘You see how upset they are. Eric’s crying!’ ” Bunim told Faraldo to do her job: she had to get Eric back on board with the filming.

When Faraldo entered Eric’s bedroom, she knew that mikes were on; she didn’t want to say anything that would antagonize her bosses further. Instead, she told me, she stared deep into Eric’s eyes, trying to communicate her distress nonverbally. Eric can’t recall the events clearly, but remembers Faraldo helping him calm down.

In the wake of the nude-photo clash, production shut down. Although the memories of the participants, on both sides of the camera, are somewhat fuzzy, the producers seem to have held more than one emergency meeting, at the loft and at Gonzalez y Gonzalez. At one of these meetings—which was attended by the cast, Bunim, Faraldo, and Verschoor (Murray was out in Los Angeles)—the debate over pebbles in the pond grew heated. According to several people present, the conversation became a shouting match, as cast members, particularly Eric, Heather, Becky, and Norm, insisted that they needed to understand the ethical rules of the show. The way that Verschoor read the mood, the cast members were threatening to walk out—and Bunim’s response made matters worse. Yes, the producers would continue planting provocations, she told the cast members. Instead of resisting these interventions, they should embrace them as a fun game—a way to help the show succeed. As an experienced soap-opera producer, Bunim knew all about “packaging people,” she told them—a term she’d often used when talking to crew members, too.

This line of thought went over poorly. Verschoor recalled, “The cast was looking at her, saying, ‘What? I’m a human. I’m not an actor that you can package.’ ” Murray told me that he had a tape of the discussion, but he wouldn’t share it with me. He denied that there had been any shouting—and said his understanding was that Bunim had been explaining how the show was actually pivoting away from dodgy methods. In other words, there would be no more pebbles in the pond.

The decision was ultimately left up to Lauren Corrao, the MTV executive. She sided with the cast. Corrao told me that she “put down the hammer,” decreeing that there would be no more interference from the producers. (The “Bear Pond” moment never aired.) Verschoor felt impressed—and also surprised. Many executives would simply have fired everyone involved in the uprising, he said.

Production resumed, but the crisis had left its mark on everyone involved. Bunim was furious at Faraldo, whom she no longer trusted. The cast, however, had become even more deeply bonded to their young producer. Julie told me, fondly, “She reminded me of an R.A.,” adding that Faraldo had “no walls.” Heather described Faraldo as “the eighth cast member.” Because Faraldo was so emotionally open, she tended to leak information, in both directions. She’d talk to the producers about the cast, but she also informed the cast what she’d heard from the crew. Sometimes, Faraldo told me, her face silently communicated what was going on: “I’d look green, and they’d ask me what was going on, and I’d say, ‘Don’t ask.’ ”

Verschoor told me that he sympathized with Faraldo’s distress, but also thought she was “unravelling,” losing perspective. He said that she played an irreplaceable role for the production, though. “They really liked her, and they would open up to her. I didn’t want to betray that trust—because she was getting information we needed.”

The filming continued until mid-May, with the cast doing the kinds of things artsy kids did in New York in 1992. The housemates had fun at a roller disco; a few of them road-tripped to a pro-choice rally in Washington and worked as volunteers for Jerry Brown’s Presidential campaign. Julie befriended a woman who was homeless, then spent the night with her in the West Side Boat Basin. Becky recorded music. Julie and Heather visited a class that Kevin was teaching at N.Y.U. There were a few contrived events, like a photo shoot for Eric that was booked by Bunim/Murray Productions, but, mostly, the housemates did as they pleased. The hunt for authenticity had its absurd side: according to Andre, when the members of his band tidied up their crash pad, the MTV crew spilled some Cheerios back on the floor, to maintain proper grittiness.

Ultimately, three plots dominated the season. The first was a rule-breaking hookup between Becky and Bill Richmond, the co-director, during a trip to Jamaica. The second was a mirror of the political moment: Kevin, who is Black, had debates about race with nearly every other cast member, difficult conversations that were shadowed by the trial of the Los Angeles police officers who had beaten Rodney King, which was going on, in California, throughout the “Real World” shoot. At the time, Heather—the only other Black person in the house—had little sympathy for Kevin’s frame of mind. “I was, like, ‘Yo, why are you so serious about everything? This is not the place and the platform,’ ” she told me. Decades later, she saw it differently: “He was frustrated, the same way that people are frustrated now. I didn’t understand it and I didn’t want to understand it, because I was in party mode.” If Kevin was angry, she said, “sometimes, you don’t know where to put that anger. But he was not wrong for feeling that way.”

The show’s other central story line was a romance between Julie and Eric, a hookup between a Southern virgin and an often-shirtless New Jersey bad boy. Julie and Eric’s flirtation didn’t actually exist, according to everyone involved—including Julie and Eric. But Oskar Dektyar, an editor Bunim and Murray had hired to work with Alan Cohn, was determined to find romantic tension between them in the seventy hours’ worth of footage that was compiled. One day, he told me, he stumbled upon the perfect sequence: Eric slurping spaghetti off Julie’s plate. As if he were constructing fan fiction, he built a playful montage of the two, with shots of Eric making cow eyes at Julie, then cuddling a kitten. He scored it to “I’m Too Sexy,” by Right Said Fred. In the wee hours of the morning, exhilarated by the breakthrough, Dektyar went to a nearby park and danced for joy.

In the end, every cast member got their moment, in small, satisfying stories about, say, Norm going roller-skating or Heather bonding with Julie. Even three decades later, the first season of “The Real World” remains absurdly charming to rewatch, driven as it is by the naïveté of its attractive cast, who lounge around their loft wearing clown hats and cowrie beads, obsessively analyzing their own levels of “realness.” Heather mocks Eric as a phony who is fascinated by his own image; Andre speaks earnestly about wanting his band to be authentic. It’s a time capsule of a lost generation, consumed by the horror of selling out.

During the final episode, the housemates break into the control room, seize the cameras, and point them at the crew—a meta moment that doubled as a celebration of the production. Each talking-head interview the editors selected emphasized the integrity of the project. Becky, looking festive in pink lipstick and a gray power blazer, says, “There was nothing set up. We were all very much real about everything! We didn’t think about the cameras after, probably, like, the first week.” In the background, her housemates horse around, pretending to have a threesome—the kind of outrageous hookup their producers had hoped for all along.

“The Real World” gave Murray the blockbuster success he had dreamed of. In the years that followed, Bunim/Murray became a powerhouse institution, producing early celebreality shows like “The Simple Life,” starring Paris Hilton and Nicole Richie, and the Calabasas game changer “Keeping Up with the Kardashians.”

Still, Murray’s voice took on an edge when he spoke to me about the years of condescension he’d endured from his Hollywood peers. He knew that some people would always see reality production as “a dirty thing.” But although he had a few regrets, like the night-vision cameras he’d put in the “Real World” bedrooms in Chicago, which captured graphic footage of a cast member having sex—he’d later cut the footage from reruns—he made no apologies. He’d saved more “Real World” kids from making fools of themselves, he argued, than he’d hurt. The way he saw it, his biggest accomplishment wasn’t helping to invent a new kind of television; it was creating a new type of viewer. For the generation that had grown up with “The Real World,” reality TV wasn’t a compromise, some crummy stopgap when scripted TV wasn’t available.

Reality was what they preferred. ♦

This is drawn from “Cue the Sun!: The Invention of Reality TV.”

Sourse: newyorker.com