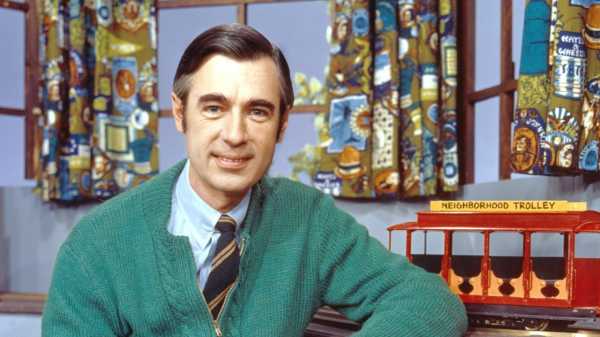

A few months ago, upon returning home from work, I hung my jacket in the closet, slipped a sweater off its hanger, put it on, and felt a small surge of pleasure. This happy feeling, I realized suddenly, had something to do with “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood”: I’d reënacted part of a ritual I’d seen there dozens of times, and it had tapped into a deep well of childhood contentment. Millions know that feeling—it’s the reason that so many are responding to Morgan Neville’s new documentary, “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?,” about Fred Rogers and his long-running children’s show, with gratitude and a sense of temporary salvation. Many childhood memories make us nostalgic, but the “Mister Rogers” emotion is something different. It involves a cardigan-wearing man teaching us, respecting us, and expressing care for us in ways that people on other shows rarely achieved or even attempted. How Fred Rogers did this, and what it means, is at the heart of Neville’s movie.

“Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood,” which ran on PBS from 1968 to 2001, has a gently spectacular beginning. Its theme song opens with a chiming harmonium. We float over a colorful model of a town and head toward a little house. As we enter it, the theme bursts into piano jazz, and Mr. Rogers, in a jacket and tie, opens the door, smiles, and sings: “It’s a beautiful day in this neighborhood, a beautiful day for a neighbor—would you be mine?” In every episode, as he sings, he performs the same ritual—going down the two steps to the closet, taking off his jacket, hanging it up, putting on one of several colorful cardigans, zipping it, sitting, taking off his shoes, chuckling, putting on his sneakers. Often, there were slight variations: some zipper whimsy, or an object brought with him, such as a football. The rituals last as long as the song, and the song was sung many hundreds of times. Fred Rogers was an ordained Presbyterian minister, and “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood,” which was secular and inclusive, was his way of preaching. “His ordination was as an evangelist for television,” his widow, Joanne Rogers, says in Neville’s movie. “It was pretty way out for the Presbyterian Church.”

“Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” doesn’t disillusion—or gratify—viewers with revelations of hidden flaws. It was “a little tough,” Rogers’s grown son says, “to have almost the second Christ as my dad.” But Neville humanizes Rogers by reminding us how strange he was, and how bold. The film opens with black-and-white footage of Rogers sitting at a piano in 1967, talking about how he’ll use mass media “to help children through some of the difficult modulations of life”—to go, for example, “from an F to an F sharp.” The performance is both affecting and dissonant; Rogers’s patient confidence, familiar from his show, feels a bit lofty. Then he seems to realize that. “Maybe that’s too philosophical?” he asks. Here, the film begins in earnest, playing the beloved “Mister Rogers” theme and unspooling colorful titles. From this awkward beginning, it seems to say, he got somewhere wonderful, and so did we.

In the early sixties, Rogers worked on a more conventional show called “The Children’s Corner.” Then, TV was still discovering itself. Neville’s film shows us clips of kids’ fare from the era—Bozo, Soupy Sales, Howdy Doodyish stuff—and Rogers’s consternation at what he saw as the misuse of the medium. “I saw people throwing pies at each other’s faces,” Rogers says. “This is a wonderful tool. Why is it being used this way?” He wanted television to value children’s feelings, to encourage listening and respect, and to express something about human dignity. “Fred was radical,” David Newell, who played the delivery man Mr. McFeely, says. He felt that the feelings of the child were as important as the feelings of the adult.

Rogers keenly remembered his own childhood, which Neville depicts through tender, fanciful animations—inspired, he said at a recent screening, by forties-era children’s books and “The Magnificent Ambersons.” Rogers grew up affluent, at times sickly—one animation shows him in bed, imagining that his bent knees are mountains—and at times overweight. “We both had childhoods where we weren’t allowed to be angry,” his wife says. Rogers wanted his show to be a place where children could recognize their emotions and learn what to do with them, and he taught this art through songs, stories, and direct conversation with the camera; when he spoke to that camera, he imagined speaking to a single person. Even if you were a kid who preferred more boisterous entertainments, or found his style too simple or too slow, it was impossible to question his integrity or intentions.. Even the music suggested a deep respect for children—in some places, it consisted of little notes sprinkled here and there, like background thoughts; at other moments, it swelled into an intricate symphony.

As the film notes, Rogers took his time on the show: together, unhastily, we observed a turtle, an egg timer, the workings of an apple peeler, fuzzy yellow chicks. I recently watched a bunch of episodes from the seventies and eighties, and journeyed, via the magic hanging screen he called Picture Picture, to a Crayola factory. As Rogers outlines what we’re seeing, over piano music, the crayon-making process is laid out before us like a Richard Scarry illustration, from pouring to dyeing to wrapping to boxing. In another episode, he shows us postcards of art by van Gogh, Miró, and Sargent, and then brings us to the “neighborhood gallery”—the show was filmed in Pittsburgh, and the gallery was the Carnegie Museum of Art—to see the actual paintings. After talking with a curator about brushstroke detail and the need to avoid touching the paintings, Mr. Rogers asks about her comment that the gallery is like a second home to her; he wants to know if it has a kitchen and a bathroom. Yes, it does, she says, and soon we’re following them into a public restroom, turning the faucets on and off and admiring the toilets.

The show wasn’t all straightforward appraisal of ducks and sinks. In the show’s daily visit, via model trolley, to the Neighborhood of Make-Believe, things got quietly far out. To those of us who grew up with it, this strange wonderland—home to duck-billed platypuses, the sweet Daniel Stripèd Tiger, who lives in a clock, and so on—makes intuitive sense. (In college, I had an elaborate dream about X the Owl, and whether or not he was modelled on Ben Franklin.) But looking at it with some remove, in adulthood, we realize that it could be a calmer version of the kind of psychedelia we associate with “The Banana Splits” or “H. R. Pufnstuf.” Neville shows us a scene from an early episode of the show, from the Vietnam War era, when King Friday XIII, described as “one of the few remaining benevolent despots,” establishes a border guard, and Lady Aberlin, the realm’s resident kind grownup, floats balloons of peace to his castle to sort things out.

This deliberate, steady combination of fantasy and reality was part of what gave the show its power. The human characters had real-sounding names but whimsical titles—Handyman Negri, Lady Aberlin. The show’s setting was recognizably domestic but also a studio, and we came to it via those neighborhood models, as though a train set had come to life. I loved the trolley to Make-Believe as a kid—its song, its busy adventuring—but I’d get especially excited at the other, rarer path into that realm, which involved Mr. Rogers going into his kitchen and plucking models off the shelf—X the Owl’s tree, Daniel’s clock, the little factory. It’s the charm of the models that made it such fun; they were little miniatures of fanciful domiciles. Implicit in this gentle, cozy artifice was the notion that our thoughts are very powerful, like our feelings, and that we can think our way into and out of places as we need to.

I don’t know too many current children who watch “Mister Rogers,” though I watched Neville’s film with an eight-year-old friend who pronounced it terrific. Rogers’s legacy seems to be more with twentieth-century kids. It’s no accident that we’ve been hearing more about him as the world has become scarier, and in recent years people seem to be quoting his “Look for the helpers” wisdom more and more. “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” offers us some hope; Rogers’s approach, the film seems to say, can be unexpectedly powerful. At one point, it features a scene from 1969, in which Rogers disarms a crabby senator, John Pastore, in a congressional hearing about funding public television. Pastore is gruff; Rogers is Rogers. “I give an expression of care to each child,” he says, with gentle determination. Then he recites the lyrics to his song “What Do You Do with the Mad That You Feel?” We watch as Pastore’s expression softens and focusses. When Rogers finishes, Pastore has been won over. “I think it’s wonderful,” he says. “I think it’s wonderful.”

Sourse: newyorker.com