From the perspective of today’s young music fan, the most unfathomable aspect of the past might be that we were once starved for images. You could listen to a cassette or a CD over and over, but staring at one of the few photographs you could find of Public Enemy or Geto Boys, on an album sleeve or in a magazine clipping, only elicited feelings of deeper curiosity. You heard the music, but you wanted to see the world that had inspired it, just beyond the frame.

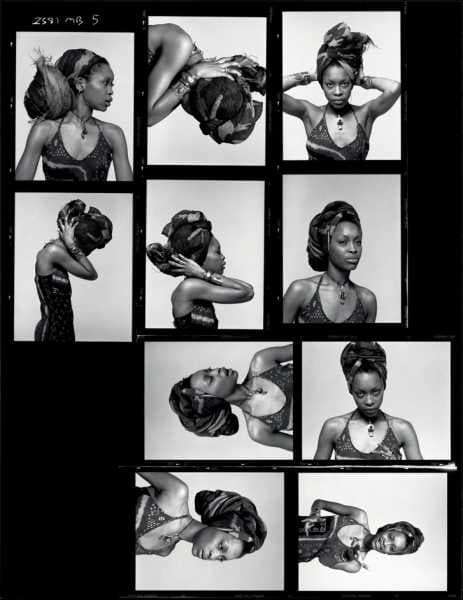

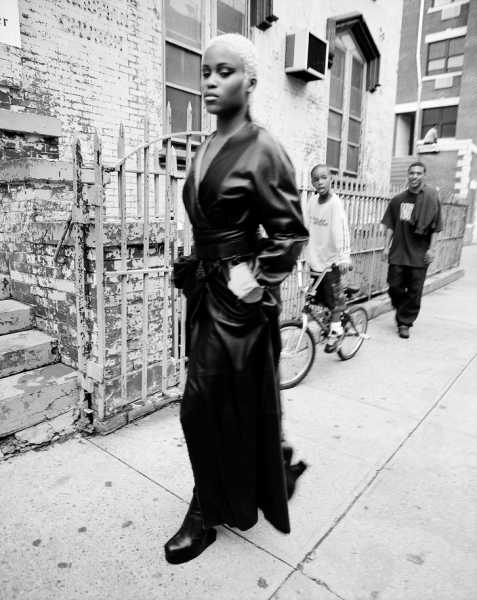

Erykah Badu, “Baduizm,” New York, 1997.

Photograph by Marc Baptiste

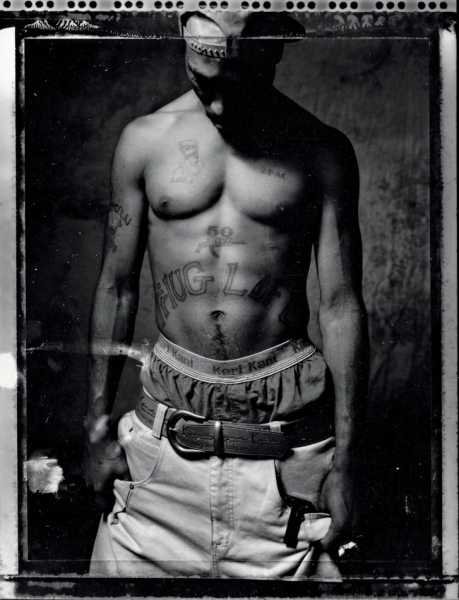

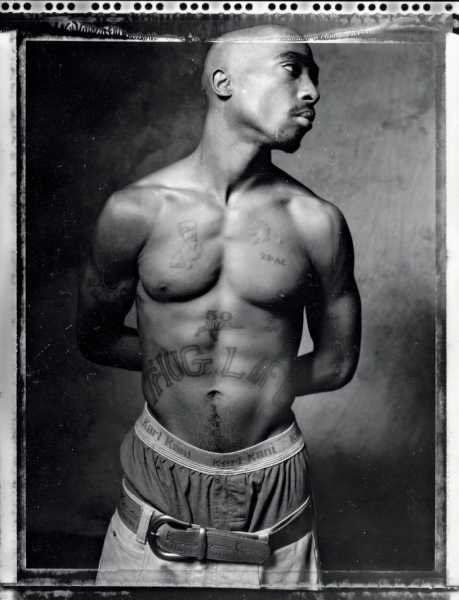

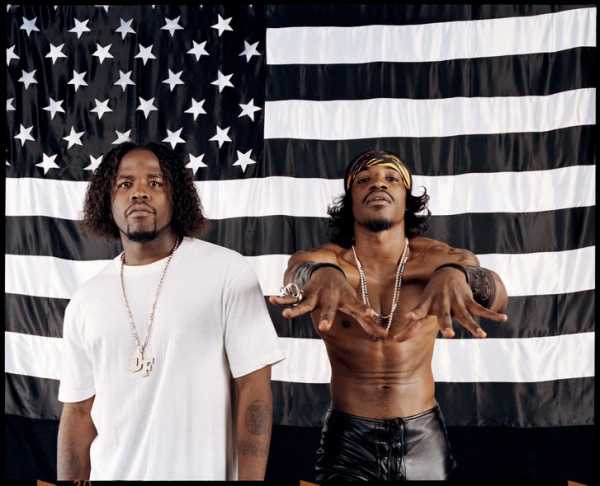

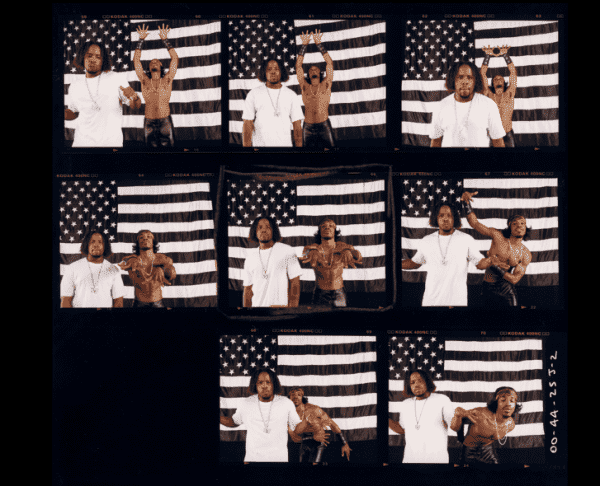

Vikki Tobak’s new book, “Contact High,” is a wondrous tribute to the way hip-hop overturned not just the sound of culture but also ways of seeing. Tobak worked in the music industry and as a journalist throughout the nineties, experiences that gave her an insider perspective on the culture’s rise. Throughout “Contact High,” Tobak and some of hip-hop’s greatest photographers return to their old contact sheets, scrutinizing all the other, considerably less famous pictures they took on their way to images that became iconic. There’s something thrilling about seeing Michael Lavine’s outtake versions of OutKast’s “Stankonia” cover, where André 3000 has his hands up rather than pointed toward the viewer in a hex, or alternate versions of Danny Clinch’s famed portrait of a shirtless Tupac and his “Thug Life” tattoo, where he’s looking down at the ground with a measure of peace, rather than toward the sky or directly at the viewer in defiance. These images are like portals into alternate time lines. There’s a lone photo of the Notorious B.I.G., wearing a crown and grinning, surrounded by a dozen versions of him flashing a tragic scowl. The crown was the photographer Barron Claiborne’s idea, meant to evoke Biggie as the king of New York. Biggie’s close friend and producer, Sean “Puffy” Combs, feared that it made him look like the Burger King.

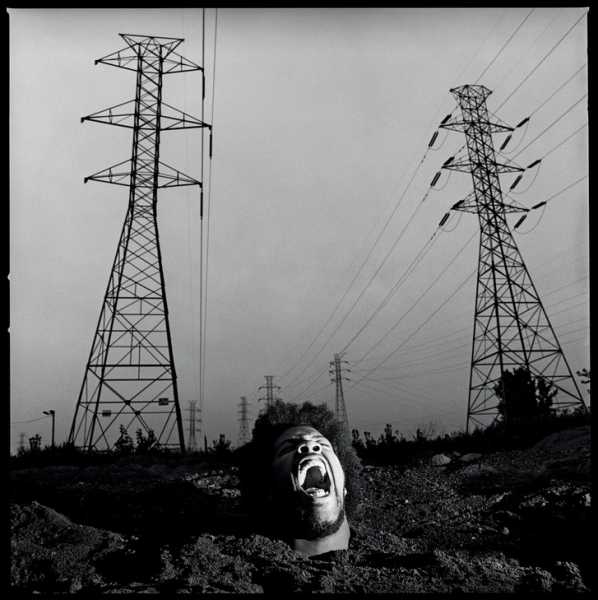

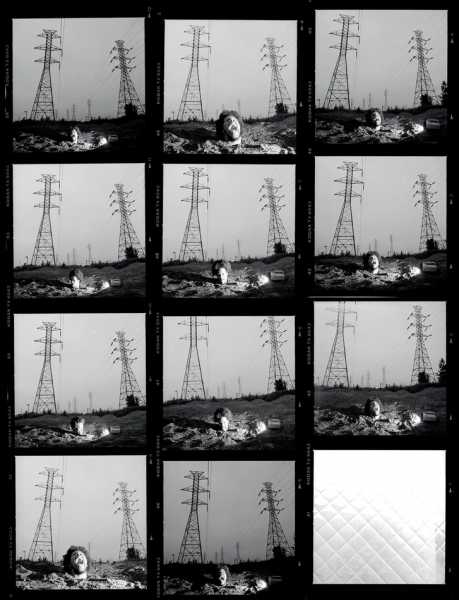

Redman, “Dare Iz a Darkside,” Newark, New Jersey, 1994.

Photograph by Danny Clinch

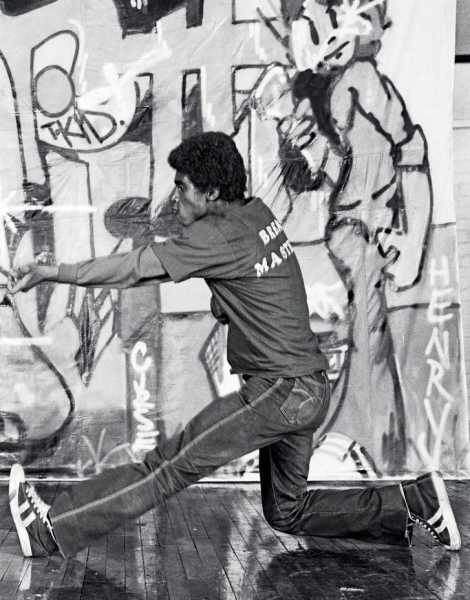

“Contact High” tells the history of how hip-hop learned to pose in front of the camera. And it gives credit to the photographers for being the ones, more often than not, who were telling the stars how and where to stand. The photographer Joe Conzo, Jr., was “a chubby kid with an Angela Davis afro” whose high-school buddies, the Cold Crush Brothers, were starting to gig outside of their South Bronx neighborhood. His late-seventies images capture the music at its freest, full of young faces in the crowd squealing in delight at seeing people just like them onstage. Martha Cooper, a New York photojournalist, obsessively took photos of dancers and graffiti writers in the early eighties, fearful that this subculture “might disappear” before anyone knew it. An image of the b-boy Frosty Freeze in the middle of his routine feels impossibly still, a blur of twisting, whirling limbs captured in a single, fleeting shot.

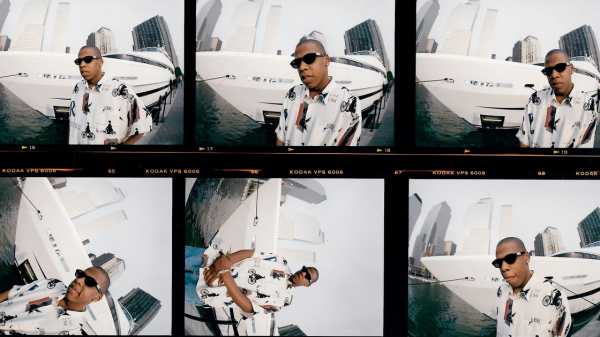

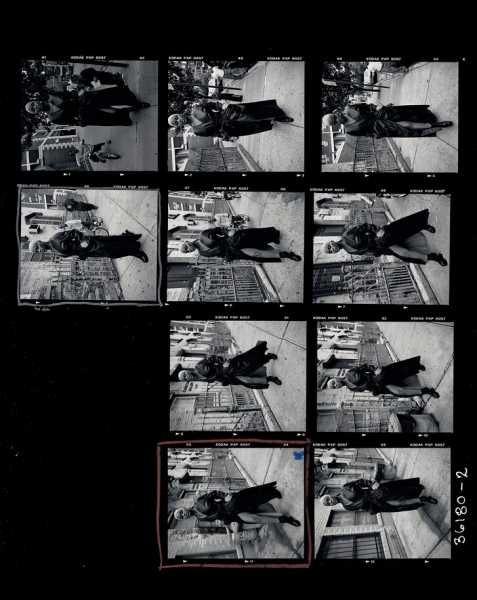

Jay-Z’s first photo shoot, New York, 1995.

Photograph by Jamil GS

Cooper was wrong, thankfully, and the spirit that she tried to capture did not disappear. As hip-hop established itself as a cultural force, in the late eighties and the nineties, the desire to myth-make in visual terms grew stronger, more conceptual. The photographer Glen E. Friedman tells a great story about Public Enemy’s “It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back” album cover. The group preferred an image of Chuck D and Flavor Flav behind bars, whereas Friedman insisted on his original concept, shot from the perspective of a surveillance camera. He was so adamant about his preference that he threatened to destroy the negatives. (He eventually lost.) The photographer Brian Cross recalls how shy and demure the rapper Ol’ Dirty Bastard became when he was asked to put his hands over the breasts of a model—a play on Janet Jackson’s famous Rolling Stone cover.

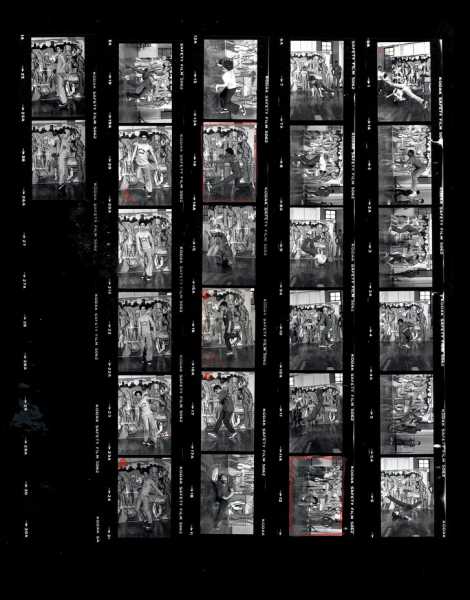

“A Great Day in Hip-Hop,” XXL Magazine, Harlem, 1998.

Photograph by Gordon Parks

Photography has become thoroughly woven into our everyday lives as a sort of running archive of our experiences. Images haven’t lost their power, especially in the age of social media, when a meme-conscious artist like Drake can shift fads by taking a dimly lit selfie. “Contact High” provides a fascinating prehistory of our present, a glimpse into a time when nobody quite knew where hip-hop could go. Tobak’s photographers often speak of bearing witness, hoping to capture a moment in time. DJ Premier, of Gang Starr, talks about how he and his crew took a picture together at the end of their album shoot—a perk of having a professional photographer around for a few hours. “Some of us made it through and others didn’t,” he says, looking at Matt Gunther’s contact sheet from Gang Starr’s “Daily Operation” session. Premier notices some guys being a little too casual with their guns, and others, like his partner, Guru, who are no longer around. “We were just young and living.”

Tupac Shakur, Rolling Stone shoot, New York, 1993.

Photograph by Danny Clinch

OutKast, “Stankonia,” Atlanta, 2000.

Photograph by Michael Lavine

Eve, New York, 2001.

Photograph by Eric Johnson

Frosty Freeze, Rock Steady Crew, New York, 1981.

Photograph by Martha Cooper

Sourse: newyorker.com